You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Jenni Fagan on her remarkable memoir recounting her traumatic upbringing

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

Jenni Fagan’s remarkable account of her often traumatic upbringing in care is also the memoir of a child who was born to be a writer.

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

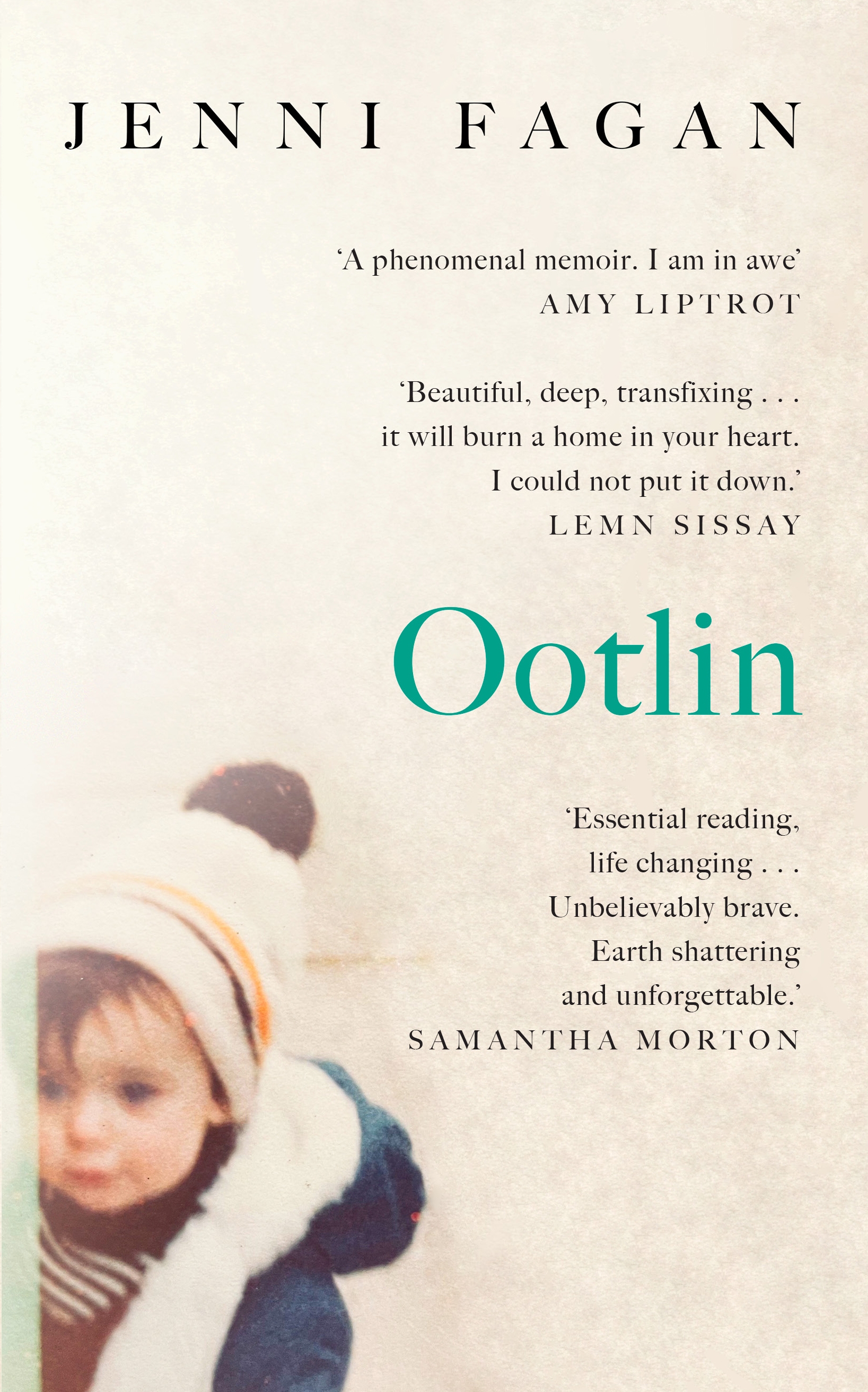

Taken into “care” even before she was born, Jenni Fagan was immediately removed from her birth mother. By the time she was five, her files recorded 27 different versions of her name; by the age of seven she had lived in 14 different homes. Throughout her childhood she suffered abuse from many of those charged with her care, endured cruelty, violence, neglect, rapes, homelessness and—without family or a sense of identity—a profound emptiness which she later tried to numb with drink and drugs. She tells the shattering story of this upbringing in her first non-fiction book, Ootlin: A Memoir. It is the book she was literally born to write, yet almost didn’t live to do so.

Fagan states in her prologue that she began the book more than two decades ago as an extended suicide note. She tells me more about this dire genesis when she joins me via Zoom from her home in Edinburgh. “In my early 20s I was dealing with the fallout of coming out of the care system. I had CPTSD—although nobody really knew what that was then—and at that young age, with no family, and having come from such a dislocated life, I just did not have the skill set to cope with it. I was trying to deal with being suicidal in the best way that I could—drawing and reading a lot, but the emotional pain was so intense I could not imagine living a whole life after the life I had already been through”.

But at the time I thought: I can’t ever look at that again. So I locked the manuscript up in a flight case and it stayed there for 20 years

In a flat so small it later inspired her novel Luckenbooth which is set in an Edinburgh tenement, she sat down to write her suicide note. “But as I was writing it, I thought, this is really sad. I’m going to leave a tiny note that does not say much at all. So before I go, I really do need to look back at the story of my life.”

Borrowing a typewriter from a neighbour, Fagan began writing. “I typed all day, every day for three to four weeks, 12–14 hours at a time, drinking coffee and smoking endlessly.” The result was a manuscript of 70,000 words. “Essentially it was a micro-version of what it has become. But at the time I thought: I can’t ever look at that again. So I locked the manuscript up in a flight case and it stayed there for 20 years.”

The end as beginning

And yet the act of having finally written her life story somehow kept Fagan from ending it. She subsequently went to university, gained a BA, a Master’s and a PhD. She became a published poet and a novelist, and in 2013 was named one of Granta’s Best Young British Novelists. And all the while she strove to keep her background in the background. “When The Panoptican [Fagan’s début novel] came out just over 10 years ago, there was a lot of interest in the fact that I grew up in the care system. I tried to deal with all of it as elegantly as I could while bringing the focus back to my work. I wanted to be seen as a literary writer, I did not want to capitalise on my upbringing or commodify it—it was too important to me.” And then in 2020, Fagan fell ill with Covid-19. “I was extremely unwell, and for the second time in 20 years, I thought I might die. And in my delirious state I understood that if I did so without sharing this story, there would be no benefit in me having lived through the kind of life I had”.

I’m putting my own neck on the line right now and it is terrifying

Ootlin (the title means roughly “outsider” or “foreigner” in Scots vernacular) finally makes public Fagan’s version of a story that was always told for her by others—social workers, doctors, schools, the police. “I remember being given my story book as a young child and being told ‘this is who you are’. And because little kids see through bullshit, I was thinking ‘I am not sure it is’”. At the age of three, while in foster care, Fagan got hold of that story book and cut up all the photographs. “It was my first radical act,” she smiles. From the age of seven she began to record her version of events in diaries which she continued to keep right through her teenage years. Ootlin draws on these diaries, and Fagan’s social work files which she was finally able to access after the 2000 Freedom of Information Act, along with her memories of events too traumatic to ever forget. The memoir also channels Fagan’s skills as a novelist and poet in a beautifully paced and vividly told narrative. The result is a story that—to borrow the words of Lemn Sissay in his cover quote—“burns a hole in your heart”.

Writer with a purpose

Fagan’s grace and eloquence in our interview brings me to tears. She also comes across as a writer with a supreme sense of purpose. A voracious reader from a child (libraries always were a saving grace), Fagan cites Maya Angelou, Roxane Gay, Tara Westover and Joan Didion as writers whose honesty she admires; along with journalist and writer Lydia Cacho who has suffered death threats for exposing abuse of women and children in her native Mexico. “When I heard her speak at the Edinburgh Book Festival, I thought: that is a writer. Somebody who is in it not just for the ego but who will put their neck on the line. I’m putting my own neck on the line right now and it is terrifying.” Consequently, Fagan and her publisher Hutchinson Heinemann plan to be extremely selective when it comes to interviews and events. “I do not want to constantly go over this story. I did not even need to publish it. I am critically well-received for my fiction, I am writing multiple TV series. I could continue my whole career without sharing it,” she says.

Extract

What can we say about a life? Any of us! We are all here living it and there must be some reason that people go through more than they think they can over and over again. I do not believe it is a meaningless act—courage—not at all, and to choose to live despite fear, or lack of safety, without so many things, is such a humane thing to do. It is hope. It is love. It is truth. It is most often unseen by much of the world but so many people live with extraordinary grace and defiance in the face of mortality and a world that can be far too hostile to the human hearts that make their homes here. I can’t say it all worked out perfectly but I am still here, questioning stories and why people tell them.

But as a writer who believes in her art “as the pivot of my life”, Fagan has come to realise that her insights into the care system make Ootlin, in her own words, “politically far more important than anything else I might write”.