You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Jenny Ireland in discussion about her début novel and the need for more characters with disabilities in children's and YA books

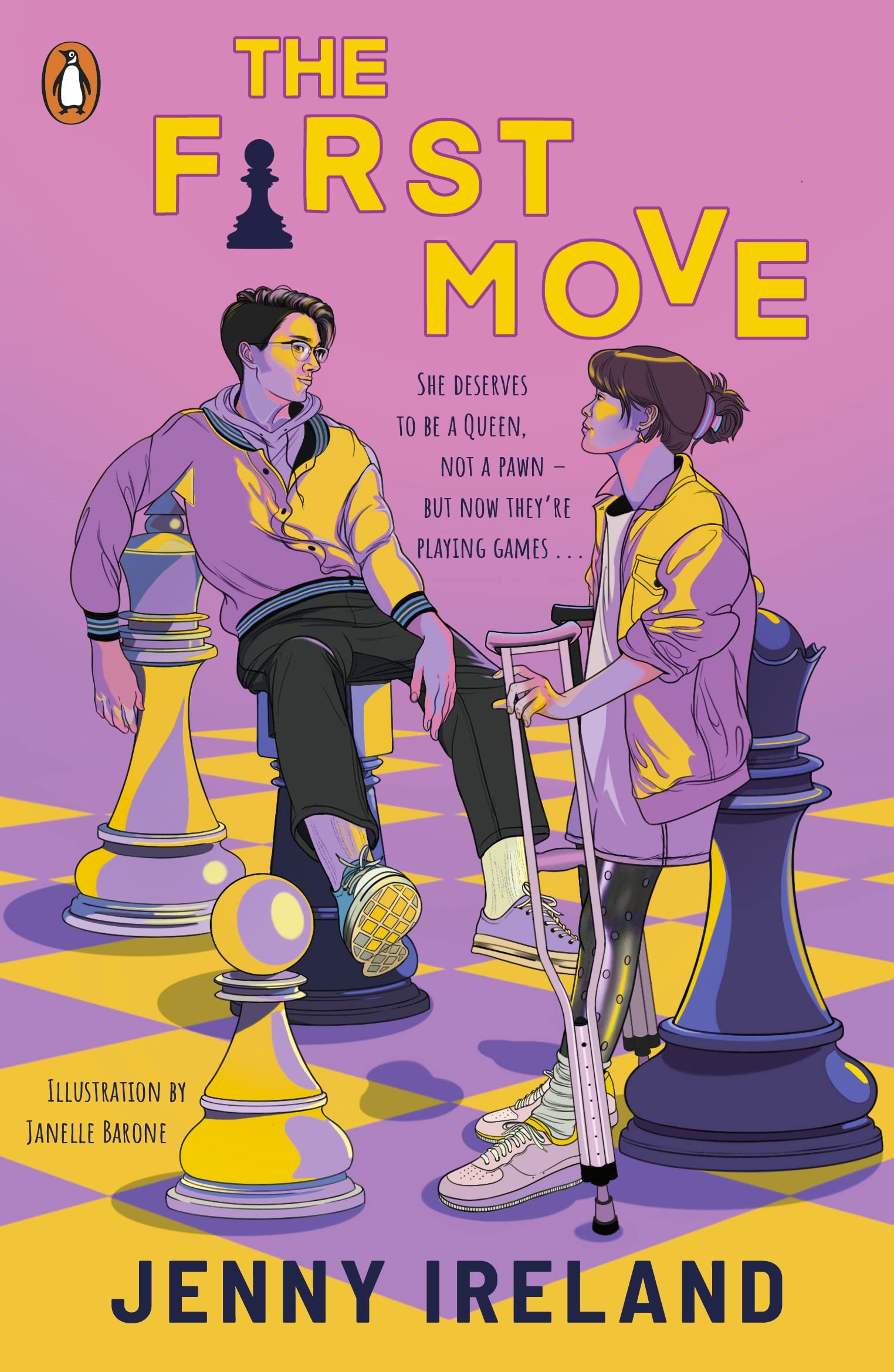

Début author Jenny Ireland has taken inspiration from her experience of living with arthritis to craft a story that represents teenage disability.

For Jenny Ireland, pain from arthritis has been part of life for 13 years. But now the Northern Irish author has tapped into that, as Juliet—the teenage protagonist in her début novel The First Move—suffers from the same condition she does.

In 2010, when Ireland was 23 years old, she gradually developed swelling in her knees, elbows and neck. After a series of medical tests and appointments, she was diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis, a chronic disease that causes joints to swell and stiffen. Like 10 million other people in the UK, she was forced to adapt to fatigue and joint pain that she says now leaves her needing to lie down most nights by 8 p.m.

During the period around her first diagnosis, after having studied French law, Ireland worked as a paralegal. “It wasn’t the career for an anxious person,” she tells me over Zoom from Belfast. Ireland quit law after getting married and starting a family. But just weeks after each of her two children were born, she suffered months-long arthritis flare-ups that left her unable to walk. Bedridden and home with young children, Ireland began writing.

I would love it if my kids grew up reading stories of kids their ages with disabilities and chronic illnesses

“I think I went mad from sleep deprivation,” she says about the time when her kids—now eight and nine—were little. “I wrote one story, loved it, and got absolutely hooked.”

Over the next five years, Ireland wrote four novels, all unpublished. Then, in 2019, she suffered another serious health scare. “All I remember is having a sore throat before it happened and feeling really depressed for a day or so,” Ireland recalls. She experienced headaches, vomiting and a spinning room before admitting herself to hospital. She was sent home—the doctors believed it was a migraine.

“It got worse over the weekend, though,” she explains.

“I went back to hospital, and I don’t remember the next part of it.”

Upon waking up one week later, Ireland was told the virus had developed into encephalitis: inflammation of the brain. While unconscious, she underwent two brain surgeries and had a tube implemented to drain fluid from her brain to her abdomen. Although she’s now recovered, the tube is there to stay.

Ireland was shocked but her father, a doctor, was not. He knew she likely developed the virus soon after her monthly injection of the medication she takes to ease joint pain. This vulnerable period after injections suppresses the immune system and can turn an everyday virus into a life-threatening one. Ireland spent the next five weeks in hospital, rotating between intensive care, high-dependency care and a ward.

Although the hospital experience can be called traumatic, for Ireland, recovery was the hardest part. In the six weeks after leaving hospital, she could barely walk and her short-term memory noticeably suffered. She gained two stone in body weight from her required steroid medication. In just over a month, her entire appearance changed. Ireland says: “I hated that [the weight gain] bothered me, but it did. I had been put through all that and I didn’t even look like myself any more.”

Again, unable to walk, Ireland returned to writing with a new perspective. Reflecting on how her disability had affected her health, Ireland took inspiration from her life to craft a teenage protagonist with arthritis—and, slowly, what would become The First Move started to take shape. “Living with arthritis for so long, it was a no-brainer for me to have a disabled female character as my lead,” Ireland says.

Teenage heroes

For Ireland, the lack of disability representation in books—especially children’s and YA fiction—is shocking. While 15,000 young people in the UK are affected by arthritis, it’s still widely believed to be a disease that affects just the elderly—and rarely do characters with arthritis show up in children’s books. “I would love it if my kids grew up reading stories of kids their ages with disabilities and chronic illnesses,” Ireland says. “That is just the world we live in, so it makes absolute sense to me.”

With this goal in mind, she wrote Juliet, a teenage wallflower with arthritis who doesn’t believe she is worthy of romance. Although Ireland wasn’t diagnosed with arthritis until her twenties, the writer empathises with what it would have been like to live with the disease as a teenager. “They have my respect,” she says of teenagers living with disabilities. “It’s hard enough being [that age] without adding on top of it. Any teenager going into school with that something extra is a hero.”

I don’t freak out about the tiny things any more. I’m more inclined to go for it and write about what I want

But Ireland’s real-life inspiration didn’t stop there. Her husband had always been a chess fanatic and had tried to spark her interest in the game for years. After they watched “Magnus”, the 2016 documentary about Norwegian chess grandmaster Magnus Carlsen, she was finally hooked. After learning the game, Ireland saw chess as the perfect setting for a will-they-won’t-they romance. She wrote Juliet a love interest, Ronan, who she would meet through an online chess game. In the novel, the pair fall in love without realising they know—and hate—each other in real life.

Making her move

Ireland found joy in writing her characters—but she remained extremely ill. Still recovering from surgery, she decided to submit a preview of her novel to Penguin Random House’s award-winning programme WriteNow, a mentorship scheme that guides new authors from underrepresented backgrounds. Ireland says: “I was addicted to competitions, and you could just spend so much money entering them. But this one was free, and it was only 1,000 words. I was still pretty ill, but I just thought, ‘I’m gonna give it a go.’”

In 2020, she was chosen for the scheme, and began having regular calls with an editor who coached her through finishing the novel. Then, in the autumn of 2021, Ireland was offered a two-book deal with Penguin Random House. “My kids still remember it as the day I said the ‘F-word’ three times in a row. Of course, it was truly warranted. It changed my life completely.”

In a “whatever-doesn’t-kill-you way”, Ireland credits her encephalitis with giving her the confidence to write about chronic illness. “[Since my surgery,] I don’t freak out about the tiny things any more. I’m more inclined to go for it and write about what I want.”

Specifically, Ireland focuses on empathy and hopes to show through her writing that what we assume about others’ lives is usually incorrect. “I wanted to show that trying to understand why people might act the way they do will make the world a nicer place,” she says

Extract

You know which movies are the worst? The ones set at Christmas. Teenagers with above-average good looks, festive jumpers and mistletoe, Tiffany boxes and fake snow, wrapped up with perfect smug smiles.

Don’t even get me started on Disney movies. Targeting five-year-olds with their happy-ever-afters? It’s sickening.

Here’s a spoiler. Real life doesn’t work like that. Real life is a first kiss with way too much saliva, with someone you barely know, behind the sports hall at breaktime. Your best friend is keeping lookout and whispering that you’re taking too long, when you’re only trying to figure out a polite way of stopping the slushy horror show. Real life is your other best friend doing way more than kissing, with someone else, at the same time, a few metres away.

Real life is the doctor handing you disgusting grey crutches and telling you that you’ll need to use a walking aid for the foreseeable future.

Real life is staring at yourself in the mirror and trying not to despise your new reflection.

In real life, all your problems aren’t solved over the course of ninety minutes. There is no witty voice-over, no strategically placed plot points, and definitely no over-emotional soundtrack telling you exactly how to feel. Because real life is nothing like a stupid movie

That she will see her name in bookshops in just a few months’ time feels “unbelievable” to Ireland. She knows people will come to the novel with their own unique experiences and takeaways—that as soon as it goes out there, it’s “not hers” anymore. But Ireland hopes people will see themselves in the characters even if they don’t struggle with the same issues as them. “I didn’t want it to be a novel-length whinge [about living with a disability],” Ireland explains. “I hope I have achieved a love story of two people with their own problems, and one of them just happens to have arthritis.”