You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

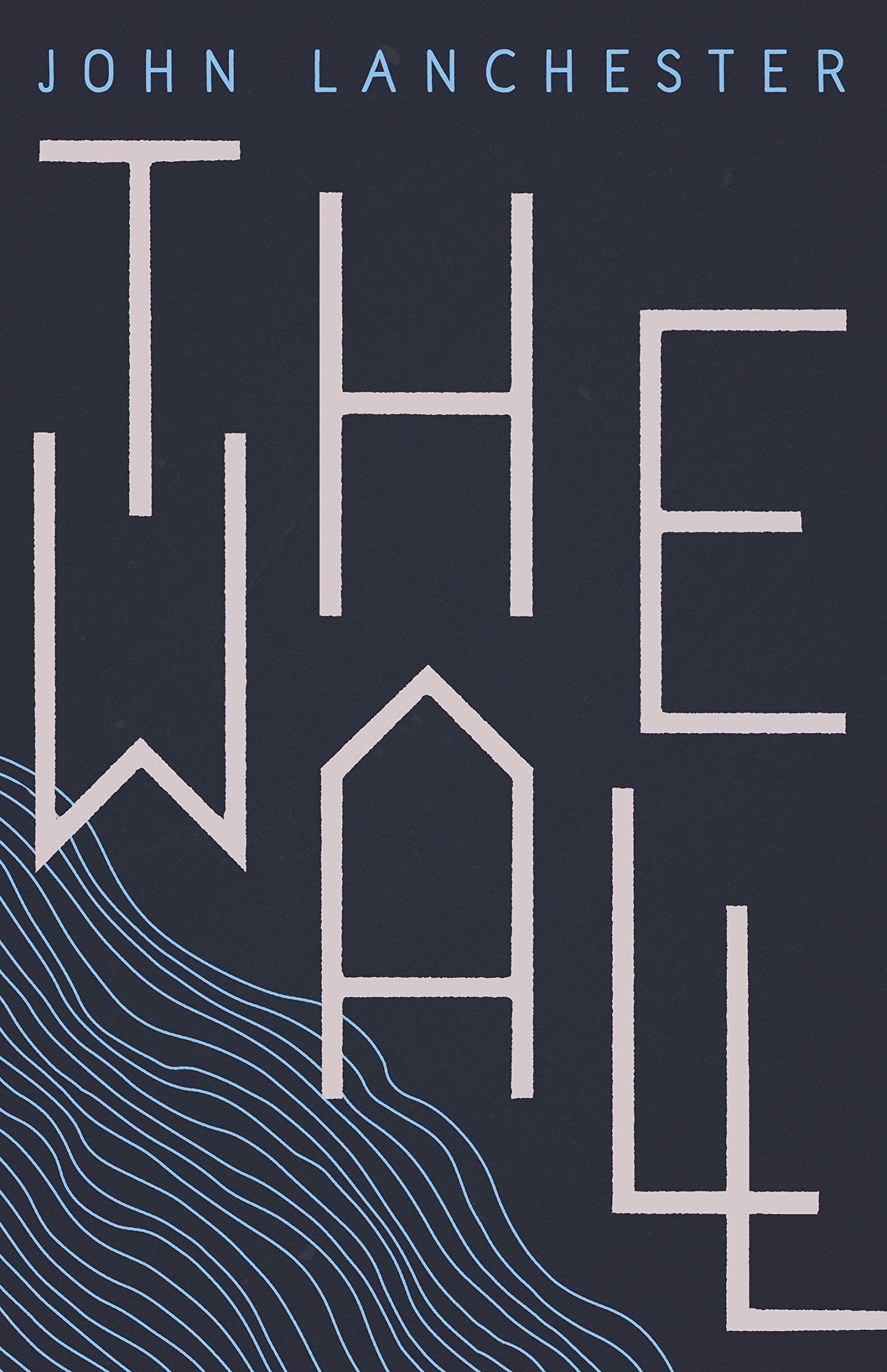

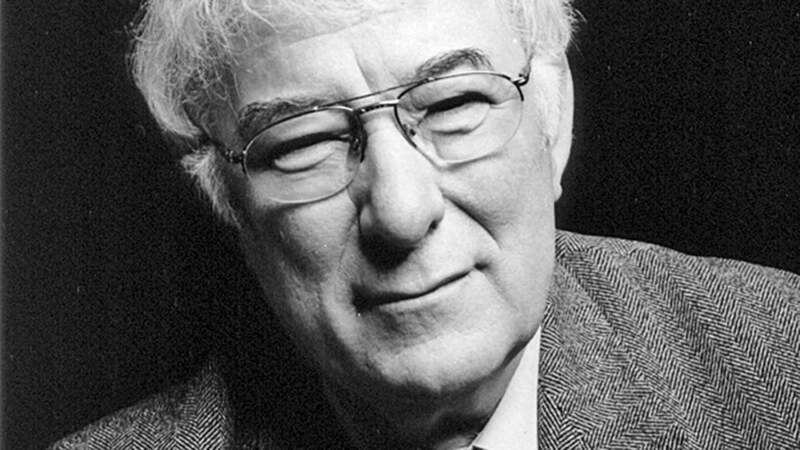

John Lanchester in conversation about the inspiration and meaning behind his novel The Wall

John Lanchester’s new novel imagines a near-future world, recognisably ours, yet irredeemably broken

John Lanchester’s previous novel, the bestselling Capital (2012), was a state-of-the-nation novel set on a single gentrified street in London, a city on the brink of the financial crisis. As Colm Tóibín put it: “Capital comes in a great tradition of novels which are filled with the news of now, in which the intricacies of the present moment are noticed with clarity and relish and then brilliantly dramatised.”

In his long-awaited new novel The Wall (Faber, Janauary), Lanchester turns his attention from the present moment to the very near future and a world that is recognisably ours, yet irredeemably broken. The novel is narrated by a young man, Kavanagh, and begins just as he is starting a two-year stretch patrolling the Wall or, as he sees it, 729 more nights. The best thing that can happen is that he survives, gets off the Wall and never has to go back.

Kavanagh, we learn, is a Defender, part of a squad which must protect a small section of the Wall—officially known as the National Coastal Defence Structure—which stands five metres high at the seaside and runs for 10,000km in total. They are defending the Wall, and thus the UK, against Others who are desperate to breach it. The Others Kavanagh is prepared to fight will come by boat—the possibilities range from a dinghy to a warship—and the punishment for failing to kill any Others who make an attempt on the Wall is to be put to sea yourself.

The reader sees the world through Kavanagh’s eyes and, as he is focused almost entirely on the present, there are only the briefest references to what has happened in the past and why this new world has been constructed around keeping people out. We glean there has been something referred to as “the Change” and that there are no beaches anywhere in the world and deduce there must have been some kind of environmental catastrophe.

It was cold, it was dark, it was wet and I had a sense of someone standing guard

When I met Lanchester at his publisher’s office in central London, he explains that he had been thinking about climate change for a while, “in the same way that I think a lot of us do, which is reluctantly, as we’d rather not think about it”. One particular paper in the scientific journal Nature alerted him to the concept of “climate departure” which is, he explains, the moment at which the coldest day in the future is warmer than the warmest day in the past. “So the new normal is hotter than anything humans have lived through.” It will come at different times in different places, with severe ecological and societal consequences for everybody.

He was also having a recurring dream about someone on a wall: “It was cold, it was dark, it was wet and I had a sense of someone standing guard.” The dream, he realised, was linked to the environmental science he had been reading and thinking about, and so the idea for The Wall was born.

The novel wears its research very lightly, though. “I’m quite wary about research in fiction,” he says. “Partly because I write non-fiction and you can put things you know in non-fiction. You can’t put things you know in a novel in quite the same way because explanations are rather damaging to fiction, I think. In one sense it’s the most researched novel I think I’ve ever written, and in another way it’s the most directly transcribed from my imagination it is like something I dreamed.”

Flash-forward

Lanchester, who is also a journalist and currently contributing editor to the London Review of Books, starting writing The Wall during the summer of 2016 which was, of course, the time of the Brexit referendum. It is, I think, a state-of-the-future-nation novel, a vividly realised, prophetic novel about where we could feasibly end up if today’s anti-immigration fears are continually stoked and magnified by certain politicians. “I didn’t think of it as a reply [to Brexit],” Lanchester says, thoughtfully. “It was [based on] a dream, but I suppose the dream was partly about the lines that we are on and… just staying on them. One of them is climate change, and the other is society and politics and our sense of ourselves and what our values are.” Later, he describes the novel as “a story set in the world we are making”.

I think that is why I have a different emotional reaction to questions of immigration, because if people want to come here, then that makes me feel safe because it means I’m in the safe place

There were no conscious literary models for The Wall, he says, although he was always a big reader of SFF and speculative fiction growing up, “so I didn’t panic when I found myself writing a book set in a version of the future”. He echoes William Gibson’s belief that speculative fiction is always a way of writing about the present. “Things that are set elsewhere get their kick, or their sting, from what they tell us about now.”

The novel was also doubtless influenced by Lanchester’s own background. He grew up in Hong Kong and left aged 18. “I was aware every day that people died trying to get over the [Chinese] border. People drowned swimming across the bay. There’s a street in Kowloon called Boundary Street, and if people got to Boundary Street they couldn’t be repatriated, they were safe. Everybody knew that and it made a profound impression; the idea that you were in a place that was safe, that other people were desperate to get to. I think that is why I have a different emotional reaction to questions of immigration, because if people want to come here, then that makes me feel safe because it means I’m in the safe place. I’m not in the place that people are literally dying to get out of.”

Shock tactics

The Wall is a powerful emotional read which is as gripping as any thriller. Without revealing spoilers, there are a couple of violent encounters, and I wonder if those were particularly hard to write? “I thought about them a lot. It’s one of those things; the only books with violence in them can be the books that only have violence in them.” These scenes are drawn out over pages and are both shocking and hold-your-breath tense. Lanchester says: “Violence is always deeply shocking in real life and I wanted to preserve that. I wanted it to feel in the text the way it feels in real life.”

I do have a very simple hope for the book; that I’m wrong

One of the central themes is betrayal. Kavanagh is betrayed by one of the characters, who I shan’t name, but, as Lanchester points out, “the issue about betrayal is who gets to define it because in one sense [the betrayer] is the hero of the book, morally. But of course it doesn’t feel like that to Kavanagh.” The novel also touches on another sort of betrayal, that of the older generation who effectively allowed the environmental catastrophe to happen to the young. “It is something I think about,” says Lanchester. “About the world we are leaving behind us, about how that is going to look when people think about us in x decades.”

So does he have a particular hope for the novel? He takes his time answering: “I do have a very simple hope for the book; that I’m wrong.”