You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Jon Klassen reflects on his writing career ahead of his latest book The Skull

Charlotte Eyre

Charlotte EyreCharlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed the

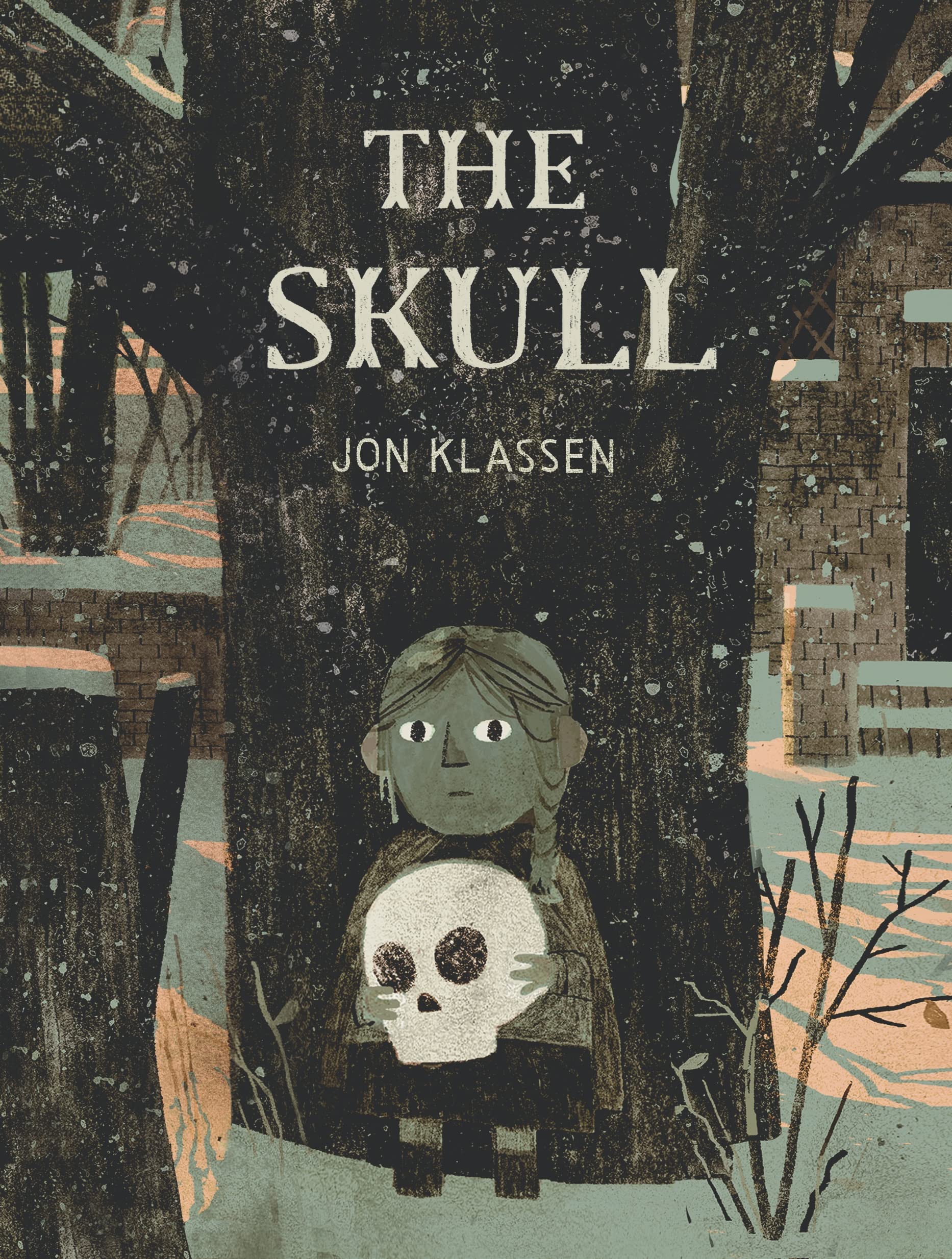

...moreCanadian artist Jon Klassen’s latest project is a deliciously creepy story about a girl and the skull she befriends in a mysterious mansion in the woods.

"When I was little, when I would visit libraries I would go to the scary section, or at least the mystery section. I’d never done a book that fits on that shelf before and this seemed like a good way to do that.” Canadian artist Jon Klassen is talking about his upcoming project The Skull, a deliciously creepy story about a girl, who is fleeing something unknown, and the skull she befriends in a mysterious mansion in the woods. They dance, eat pears, get rid of a skeleton that paces the corridors at night, and this being a Klassen book, there is darkness to the narrative, mysterious parts of the plot that are never fully explained, and humour. The illustrations are, of course, also full of wit and flair.

The book was inspired by a Tyrolean folk tale the author found in a library, although the original had much more of a redemptive ending, with a curse being broken and the skull turning back into a living being. In Klassen’s version, Otilla fulfils a hero’s journey of sorts but there are still unanswered questions about who the skull really is and why Otilla is there in the first place. Does Otilla’s running away represent a child’s loss of innocence, for example? Klassen thinks questions such as these should be answered by the reader.

That’s a funny situation for a skull to be in, even though we don’t milk it very much… Hopefully there’s a retroactive laugh when you picture him rolling around the house and swearing at things he can’t do

Ottila is brave, says Klassen, and perhaps guarded because she has been through something that isn’t explained. “My characters are usually pretty stoic. If they are going through emotional turmoil, they don’t like to show it. And there are ways of drawing that or stating it where you don’t make it bombastic or traumatic, even though the emotional stuff is hopefully fairly important.”

He has a soft spot for the skull, who tries to be a good host when Otilla arrives but is ultimately just a skull rolling around on the floor. “A lot of my books are about confusion and a feeling of only being partly in control. I think there is a reason he’s a cursed skull and I was super into the idea that he wasn’t a great guy and she knows that, but she’s running away. She takes him for who he is when they meet.”

There is a lot of humour, too. “What was informative for me was when I told people about the story when I was working on it, the first chuckle always came when they heard the skull [didn’t have a body]. That’s a funny situation for a skull to be in, even though we don’t milk it very much… Hopefully there’s a retroactive laugh when you picture him rolling around the house and swearing at things he can’t do.”

I have enough of my own work out now that it doesn’t feel so precious or paralysing to make more. I think I’m getting looser, so maybe that means I’ll do more on my own

The colour palette Klassen uses complements the story perfectly, being full of grey, black and white, with splashes of pinky tones to show where the light comes in. He was inspired by a childhood favourite book called Sam and the Firefly, which was illustrated using “one big teal colour” and complementary splashes of yellow. “But for this one I wanted to go with something a bit different and I love that peachy pink,” which helped show sunlight and sunsets, emphasising the transitional moments in the story. There is darkness round the edges of sunlight and sunsets, which helps create a spooky atmosphere to this story; the light never fully breaks through.

Critical acclaim

Klassen didn’t initially set out to be an author and before making children’s books, he studied animation, later working as a storyboarder and designer for studios. Early illustration projects were just experiments, he says, but when publishers began to show interest he left animation to try and make books full time. The first he wrote and illustrated, I Want My Hat Back, was published to critical acclaim and the follow-up, This is Not my Hat, was the first book in history to win the Caldecott Medal in the US and the Kate Greenaway Medal in the UK, and is now a firm favourite with families around the world.

“The response to that book, awards-wise, was certainly very nice, and it helped solidify the professional ground underneath me a lot,” he says. “If I didn’t have a job making books before I certainly had one after, which is all you can really hope for if you find something you want to do. Also it does give you some permission to make slightly weirder things in the follow-up time, if you want to. The third book in that hat book series, We Found a Hat, is weird, but it’s my favourite of that set, and the last picture book I did, The Rock From The Sky, was probably the weirdest one I’ve made at all, but I like that one too. I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t have gotten to make those books, or even tried to, it if it hadn’t been for This Is Not My Hat.”

The Skull will be the fifth book illustrated and written by Klassen, who has also worked with collaborators such as Mac Burnett, with whom he created Sam and Dave Dig a Hole. Klassen “loves” collaborating but might concentrate on more solo projects in future, saying: “I have enough of my own work out now that it doesn’t feel so precious or paralysing to make more. I think I’m getting looser, so maybe that means I’ll do more on my own.”

Planning ahead

For now, there is a trip to the UK this summer to plan, which will involve an appearance at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, and Klassen is planning on developing a series of board books for young children.

Extract

Otilla ran and ran.

She ran through trees and up hills. She ran for a long time. All through the night.

Otilla had grown up in this forest, but after a while the trees began to look different. They were getting closer together.

Otilla kept running.

As she ran, Otilla began to hear her name being called. She couldn’t tell if it was someone’s voice or the wind in her ears.

“Otilllllaaa.” “Otiiiiillaaaaaa.”

“Otilllllaaaaaaa.” “Otillll-”

Otilla suddenly tripped on a fallen branch and fell hard into the snow. She didn’t get up. She could not run anymore. She listened for her name, but now it was quiet.

Otilla lay in the snow and the dark and the quiet and she cried. When she was done crying, she got up and began moving forwards again.

All at once, the trees stopped. She came out of the woods and into an open yard. In front of her, in the distance, was a very big, very old house.

“I didn’t know much about that end of things before we had kids ourselves, and reading the better ones has been really interesting. They don’t have to be stories, even. There’s something else that can make them work, more like poems or songs. Plus they can be very simple, all around, and that is always good bait for me.”