You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

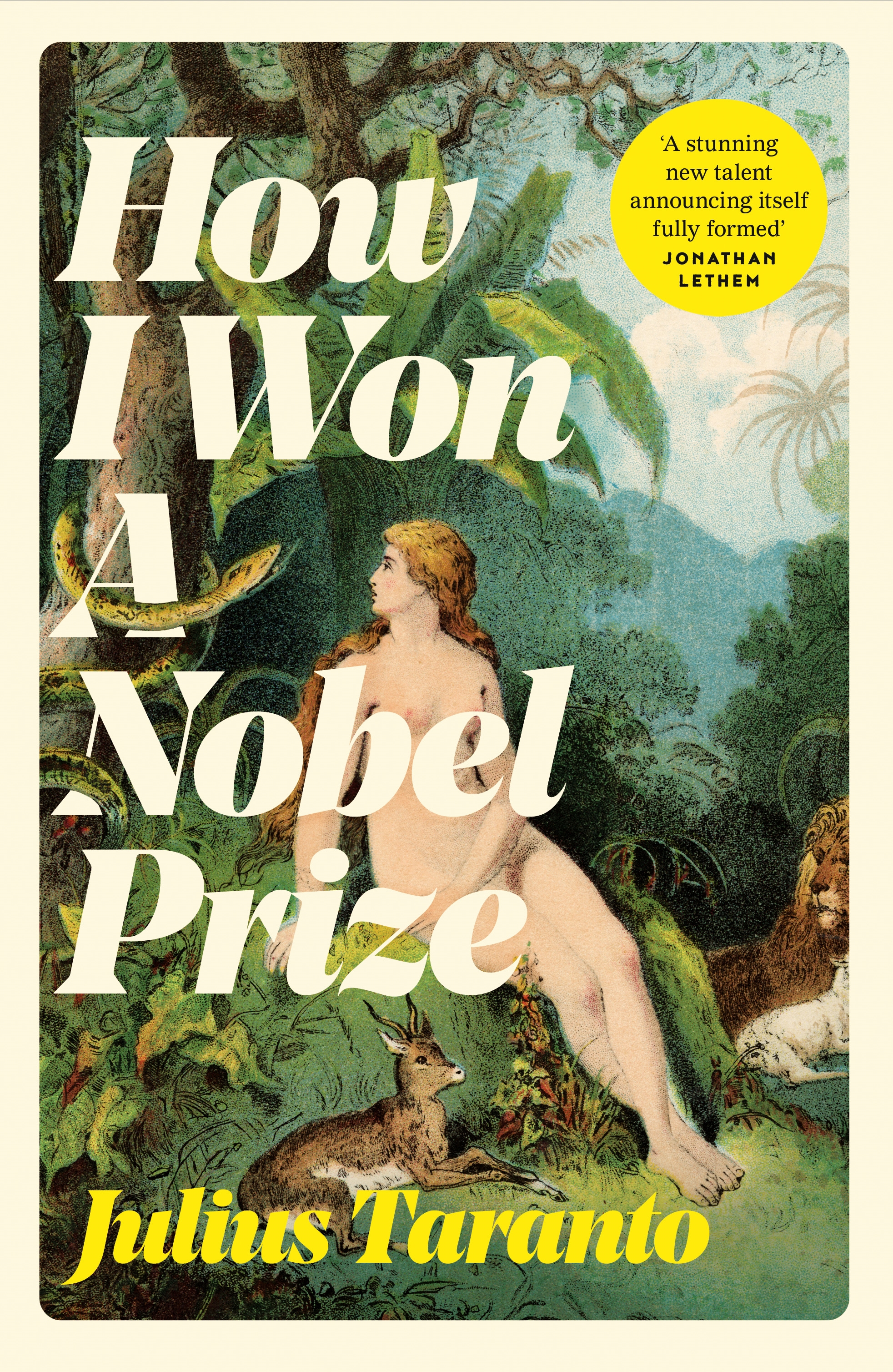

Julius Taranto in conversation about his satirical début novel, How I Won A Nobel Prize

Début author Julius Taranto takes on the controversial topic of cancel culture in his novel, examining morality, politics and ethics.

"I was nervous about it. You’d have to be crazy not to be nervous about writing about it no matter who you are,” says Julius Taranto over a video call from his home in New York City. “I happen to be white and a man, so that added extra anxiety, but in a certain sense that was part of the challenge.” Taranto is talking about his début novel How I Won A Nobel Prize, a deliciously satirical exploration of cancel culture, politics and ethics.

In the novel, Helen is a “generational talent” bent on discovering the key to high-temperature superconductivity as a possible solution to the climate crisis. However, when Helen’s graduate supervisor Perry is exiled to a new university called the Rubin Institute Plymouth, after having a relationship with a student, she is forced to join him there to continue her studies.

Funded by billionaire Buckminster Witherspoon Rubin, the Rubin Institute is unlike other universities. Here the faculty consists almost exclusively of white male intellectuals and academics who have written, committed or said morally reprehensible or criminal things. At the institute only the work matters, not the moral fibre of its inhabitants. This haven for “the worst-behaved of great minds”, Taranto writes, is a beacon of public controversy, and working there creates a rift between Helen and her husband Hew. As Hew becomes politically galvanised against the institute, Helen is left questioning her own political ambivalence and whether a life immersed in science can be entirely removed from bureaucracy. “Why shouldn’t I put my limited mental capacity into something productive? Why would anyone want me to spend my energy developing the ‘right’ opinions?”, considers Helen.

In the end I think it’s a very personal thing, the way any individual relates to a particular political moment

Many wouldn’t go near cancel culture in their début novel, I say to Taranto, yet this was a “charge” for him while writing: “That sense of danger people have going into the book should be part of the fun.” How I Won A Nobel Prize was published in the US in September to acclaim, and Taranto laughs when he tells me how he has been “getting texts, emails and phone calls from people where they’re not even necessarily saying, ‘I think the book is great’, they’re just so relieved that I didn’t turn into a total jerk.”

Quantum physics

For those who may be flinching at the thought of high-temperature superconductivity, vividly recalling days of classroom study, in the novel it is not only comprehensible but explained in such a way that Helen’s take-no-prisoners narrative voice shines through. Taranto’s background as a lawyer helped distil the scientific descriptions, but it did not help when it came to selecting one of the largest physics problems of today. “I called an old friend of mine, who happens to be a quantum physicist, and I asked him whether he had any ideas...Once he started describing high-temperature superconductivity it felt right both because I could understand what he was saying and because I felt I could explain it to readers.” Helen also “needed a problem that was important enough that as readers we would understand the ethical choice she’s making to go to [the institute]”.

Through Helen the novel posits whether everyone must be preoccupied, or at least aware of, the wider political environment. “There’s a pretty good argument that the best use of her time and energy is to work on the physics problems... and getting the readers on board with that with: ‘OK, actually we can agree that some people in the world shouldn’t be overly concerned with the political climate’.” However, in a setting which should, apart from the faculty, represent Helen’s ideal working environment, she is thwarted from a breakthrough as she is unwillingly immersed in the political discourse surrounding the institute. Toward the end of the novel, she reaches breaking point and her voice, normally characterised by calm detachment, becomes irate: “This institute had commandeered and derailed my life of science—my life of the fucking mind—not to mention potential progress toward room-temperature superconductivity that could literally save humanity’s future on earth!”

In my daily life sometimes I cut a corner. Sometimes I don’t recycle as much as I should, but I’m thinking about that later and then I will be good about the compost. It’s about giving back and making concessions for your own flaws

Political subjectivity, and the line between political belief and political action, is explored through Helen and Hew’s relationship as he pursues activism while she grapples with the pressure to form an opinion. Taranto explains: “In the end I think it’s a very personal thing, the way any individual relates to a particular political moment... that intersection of personality, background and preoccupations with whatever happens to be going on outside is what drives one person to join a march and another to stay at home.”

The narrative strikes a balance between humour, scientific jargon and sharp cultural analysis. It is notoriously difficult to write humour well and Taranto found himself “constantly checking... whether this was a ‘only funny to Julius joke’ or a ‘funny to other people joke’. It’s not like being a stand-up comedian where you get to go and work in small rooms and figure out what lands.”

How I Won A Nobel Prize examines questions which are incredibly relatable to western culture, but the novel tests them in a heightened, and occasionally absurd, setting which not only satirises bombastic chauvinism (the tallest building at the institute is called the “Endowment”), but also smaller moral questions. Hew, for example, demands both he and Helen pursue veganism in ethical recompense for living at the institute. It is this moral metric system which intrigued Taranto: “In my daily life sometimes I cut a corner. Sometimes I don’t recycle as much as I should, but I’m thinking about that later and then I will be good about the compost. It’s about giving back and making concessions for your own flaws.”

Taranto is now a full-time writer, “for as long as finances and psychology allow me to be”, after leaving his law career at the start of January 2023. The move from legal practice to novelist was motivated by the allure of “narrative as an art form... I think a lot of people who go into art go in because, at first, they had some kind of experience where they thought: ‘This helps me see the world in a way that I think is better than the way I was seeing it before.’ That feeling, and wanting to try and create it both for myself through the writing process and to give it to others, that’s the motivator.”

Extract

Perry appeared as usual. He tilted back in his immense executive desk chair, draped in a seersucker sports coat, miles of starched fabric spanning his huge stomach, fingers clasped across a wide tie speckled with tiny equestrians.

He was a big brilliant queer of the Oxbridge style. He had clean round jowls and wide round eyes beneath a clean wide round bald head. A geologically bald head.

Perry said, You and I will be moving to the Rubin Institute. Why? I said. Devlin, he said. Really. Devlin was one of my peers, nominally. But his code was clunky and inefficient, his models sadly lacking in physical intuition.

Whether he completed his degree or not, Devlin was destined to thrive at J P Morgan. Perry said, The rule these days, apparently, is that Nobel Prize-winners may fuck only other Nobel Prize-winners. Perry’s insistent round eyes waited for me to laugh.

The manuscript for Taranto’s second novel, set during the American Civil War, is complete and, although the setting is different, it was born from a similar “emotional impetus” as How I Won A Nobel Prize. “I was thinking about one of the times in American history when we have had social and political conflict that’s even worse and even greater than what we’re experiencing now. I became interested in the period and how individuals lived hopefully with humour and with humanity under those conditions.”