You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

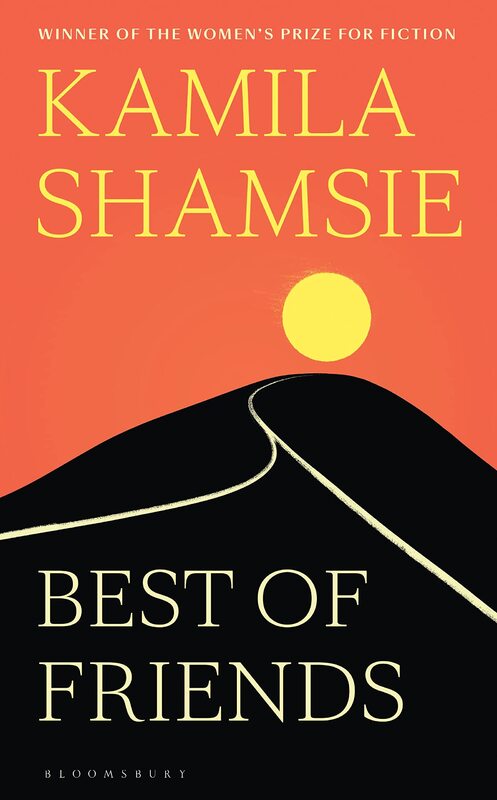

Kamila Shamsie in conversation about the changing nature of friendship in her latest novel, Best of Friends

Women’s Prize-winner Kamila Shamsie’s latest novel is a tale of childhood friends through the years.

Twenty-odd years ago, Kamila Shamsie was having a conversation with her sister who, she remembers clearly, made the following observation: “She said, ‘The thing is, the friends you make as an adult are your friends because you have something in common, but your childhood friends are your friends because they’ve always been your friends.’”

Shamsie found herself thinking about her sister’s words “again and again” as the years passed, and the seed was sown that grew into her much-anticipated new novel Best of Friends. It tells of Maryam and Zahra, who we first meet as inseparable 14-year-olds in Karachi. The year is 1988, and the girls, best friends since the age of four, share a love of Jackie Collins’ bonkbusters and George Michael posters. Preoccupied with school cliques, crushes and first dates, they attend the same private school but come from very different backgrounds and hold different values, although this makes little difference to their lives as teenagers. Maryam’s family is wealthy and she knows she will one day inherit the family luxury leather goods business. Whereas Zahra, whose father is a journalist—a risky occupation in Pakistan under the military rule of General Zia—plans to escape to university abroad.

The setting of 1988 is, of course, a hugely significant year in Pakistan’s history. It was the year that the dictator Zia-ul-Haq died and Benazir Bhutto was elected to power. Shamsie, who was born and raised in Karachi and now lives in London (she became a British citizen in 2013), remembers it well. “It was this moment where suddenly the world seemed to be transformed. To see not just a dictator go, but to be replaced by a 35-year-old woman, after 11 years of military rule... It was the most glorious thing.”

What do you do when someone takes a position that is so deeply antithetical to something you hold very deep

It is at a party celebrating the democratic election of Benazir Bhutto that Zahra makes a decision that will affect both their lives, both in the moment and far into the future: she gets into a car, with a boy she knows from school, and an older male, who she doesn’t. Maryam follows her friend into the car, and the driver accelerates away.

What takes place in the car is both subtle and terrifying; it is the first time that Zahra and Maryam realise the physical power that men have over women. Shamsie says: “As women we know that moment where something shifts, and suddenly you don’t feel safe any more. And once you don’t feel safe any more, that’s it. Until you get out of the situation.” It’s a journey that marks the end of their childhood. Afterwards, Maryam will be sent away to boarding school in England.

The second part of the novel moves to London in 2019. Three decades later, Zahra is a trained barrister who is the director of a civil liberties organisation, and Maryam is a venture capitalist specialising in tech start-ups. They are still best friends, but when two people from their past resurface, both women will need to confront not just the events that have bound them together, but the significant differences between them, which did not matter when they were teenagers. “What do you do when someone takes a position that is so deeply antithetical to something you hold very deep—what happens? I really wanted to take one of those friendships that has existed forever, and then put a lot of pressure on it.”

Getting home

Best of Friends is Shamsie’s first novel since Home Fire, for which she was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction for the third time. “The first two times I just knew there was no way I could win it,” she says frankly, but something felt different about Home Fire, a retelling of Sophocles’ Antigone, following siblings torn apart when their brother decides to follow in the footsteps of their jihadist father. “There was a moment I thought, ‘Oh god, this is awful, I’m starting to think I have a chance.’ Which is terrible, because then you have hope which could be crushed!” It did win, of course, as well as being shortlisted for the Costa Best Novel Award and longlisted for the Booker Prize. With rights selling in 25 territories, Home Fire reached far more readers than her earlier books.

I didn’t know it was possible for someone to look at a piece of work and understand so deeply

But for Shamsie, the turning point in her career came with her fifth novel, Burnt Shadows—her first novel to be shortlisted for what was then the Orange Prize. The four novels preceding that “had had nice reviews but they’d had small sales. I think that a writer today in [a similar] position, by novel three or four the publishing house would say, ‘I don’t think this is working out…’” Shamsie credits her longstanding friend and editor Alexandra Pringle, who won Editor of the Year at the recent British Book Awards, for her belief: “She never made me feel as though, if my next book isn’t a big success then I’m in trouble, and I think it’s very rare now to find editors and publishing houses that will keep faith with a writer for a number of years.” The success of Burnt Shadows “wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t written those earlier [novels] because as a writer you learn on the job, you take time to spread your wings and she really allowed me to do that. I think if there was a writer like me now… I don’t know if they would get to novel number five. That’s the sad truth about publishing today.”

The pair first met when Shamsie was 21, at university in America and determined to be a writer (a career she decided upon aged nine). Pringle was part of a contingent of agents and editors invited to speak to students, and Shamsie had submitted a four-page short story for assessment. “She raved about my story”, Shamsie remembers, laughing. “Everyone else in the room hated me, but she didn’t talk about anyone else’s work!” Then a literary agent, Pringle encouraged her to work the story into a novel. “When I sent it to her, it was just a skeleton of a novel really. There was one day in her office where we did a four- or five-hour edit. It was both at the level of the line and much bigger stuff. I remember walking out of there and just feeling my head spin. I didn’t know it was possible for someone to look at a piece of work and understand so deeply what it can be and talk to you about how to get it there.”