You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

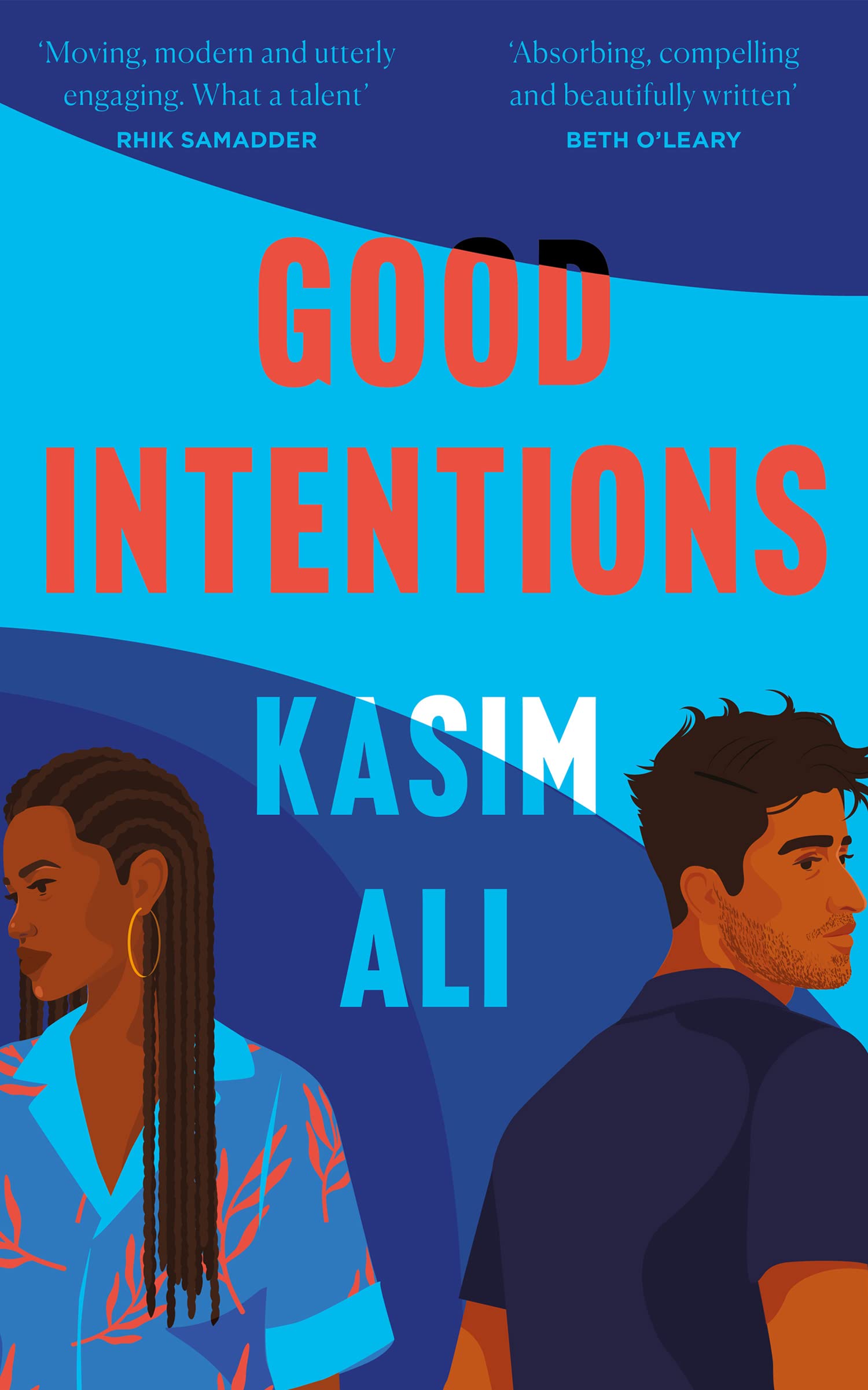

Kasim Ali discusses masculinity and race in his début novel Good Intentions

Début novelist Kasim Ali talks masculinity, his fascination with parents, and writing an interracial romance without a white person.

Kasim Ali, whose début novel Good Intentions was published by Fourth Estate in March this year, is talking about “Pachinko”, the “incredible”, he says, Apple TV+ drama series based on the 2017 novel by Min Jin Lee.

Talking over the phone from Newcastle—he is visiting from London for a friend’s birthday—he explains how he cried at every episode “because it really moved me” and “that’s the kind of person I am”.

Growing up “very poor” in Birmingham, he says “I used to feel shame in being that kind of person.” Ali “wasn’t a boy who liked football or cars, or whatever you deem to be masculine”, but someone who “read books and much more appreciated the company of the women in the family” and the South Asian community he grew up in. Like Nur, the protagonist in Good Intentions, he loves to cook. “The men in my family were like, ‘Why is he cooking, why is he cleaning?’” he recalls.

As a result, Ali was “always massively interested in the question of what it means to be a man”. It’s one of the central questions at the heart of Good Intentions, which tells the love story of Nur, a Pakistani Muslim, and Yasmina, a Sudanese Muslim; and Nur’s decision, four years into their relationship, to finally tell his family about it. Plagued by fears he is being a “bad son” for having, and hiding, a Black girlfriend, he turns to his male friends for guidance and advice.

I wanted to write an interracial romance that didn’t feature a white person

“When I was writing Good Intentions, I wanted to write about a boy who wasn’t afraid to be physically and emotionally vulnerable with his friends, who would have conversations with men in his life that were open and honest about how he is feeling. And it’s not a bad thing. Because people like that, like I, exist. And there is strength in being in tune with your feelings,” he says.

Writing the character of Imran, Nur’s best friend, incidentally became one of Ali’s favourite parts of the story, though he wasn’t planned. “Initially, I was frustrated with seeing interracial relationships on screen,” he explains when asked what inspired Good Intentions. “On the page, but mostly on screen, I think, ‘There’s a white person plus a non-white person.’ Whereas in my world, I would see all kinds of combinations, if you will."

“So I wanted to write an interracial romance that didn’t feature a white person. When I sat down to actually write that, I realised that if one of them is brown and one of them is Black, then I can talk about anti-Blackness in the South Asian community. And then I thought, my protagonist has to be a young man. So then I can talk about masculinity. And that’s kind of how the thought process happened."

“When I was writing it, it started with the very simple idea of an interracial relationship without a white person. Then all of these complexities arose through the writing itself.” Out of the writing came Imran, “one of my favourite things about Good Intentions”, Ali says. “Like, I love him. I think he is fascinating and really cool and really funny. And I didn’t plan for him. I truly love him so much because he goes through this journey in the book that I did not plan. All I knew was that Nur needed a friend. And then he became this complex character. I didn’t plan for him to be a gay Muslim. When I was writing, it just happened. It just felt right that he was [a gay Muslim].”

What I’m really interested in is the question of: do we give our parents a chance to evolve with us? Or do we just accept that they are who they are?

Imran’s relationship with his parents by turn helps Nur consider his own parents, his expectations of them. “It’s fascinating to me as the author that I sat down and subconsciously created a mirror narrative to Nur’s relationship with Yasmina through Imran. And his relationship with his parents and his family,” he says, adding that alongside questions of masculinity, parents show up again and again in his writing.

Parental guidance

The novel opens on New Year’s Eve, Nur in his childhood home surrounded by family and “the tightness in Nur’s chest grows as he watches the screen”. He thinks he knows how his family—his parents in particular—are going to react when he tells them his girlfriend is Black.

“I am fascinated by parents,” Ali explains. “Along with the whole masculinity thing, those are the two things I’m completely fascinated by. What I’m really interested in is the question of: do we give our parents a chance to evolve with us? Or do we just accept that they are who they are?”

He was wary, he says, when writing Good Intentions, of building a narrative where “[Nur’s] parents are just racist, like, capital-R Racist”, when “it’s actually got a lot to do with how [Nur] perceives his parents.”

Writing for me is such an intrinsic part of my life. Now, I’ve been doing it for so long I can’t not write. I’m always writing

“It’s about the unwillingness in him to give them a chance, because he has already decided who they are and what they are, which is something I think we are all guilty of with our parents, when actually, they’re just as human as we are,” Ali says. “My mum is 48, right. So I would like to think that when I’m 48, I will have the ability to change my mind on something. If I think that I could be that person, why is she not allowed to be that person? Why are parents generally not allowed to be those people?”

Plenty more to come

This interest in relationships and their complexity is something he is taking into his next novel. The second book in the same deal as Good Intentions, which was snapped up for a six-figure sum in 2020—after Ali wrote the novel over six weeks in 2019—is, Ali says, a book about a toxic friendship spanning 10 years.

“I’m fascinated about relationships and the kind of weights that we place on them, and I think actually what I’m referring to is the sort of social contract of relationships, like, how much burden are we willing to accept before we accept that this is breaking?” he explains.

“[These characters], they are such good friends at the start, but then you realise they are quite poisonous to one another. But it’s all about that loyalty that you have to your childhood friends, even as you’re growing and changing.”

Good news for readers is that it’s unlikely to be the last we hear from Ali. For a début novelist, it would be an understatement to call the 28-year-old prolific. Good Intentions was his 22nd novel, after he wrote a staggering 21 in the seven years between the ages of 17 and 24. “I’m writing another one now,” he laughs. “Writing for me is such an intrinsic part of my life. Now, I’ve been doing it for so long I can’t not write. I’m always writing.”

He references “a version of Good Intentions which I never wrote, but it was in my brain”, where he dives deeper into questions of class and financial inequality, things his own background and subsequent move to London and into the world of publishing—which he has worked in for five years—have prompted him to consider. Perhaps this is what we might see Ali’s eye turn to in the future.

Extract

Nur’s two weeks are nearly up and he still hasn’t said it. It’s the day before he has to go back, returning to a question that he will not know how to answer.

There can only be one answer.

He is sitting at the top of the stairs and it is nearly midnight; his parents are in the living room, waiting for the fireworks to start. He said he was going to get his phone. That was ten minutes ago. In a few minutes, the celebrations will begin.

…

The clock counts down and down until there are only single digits left, and then there is nothing and there is noise. Fireworks flash and fill their screen, are so loud that they may as well be in the room with them. His mother laughs, shouts ‘Happy New Year!’ and they all shout it back. Mariam takes a video on her phone and Nur sees but doesn’t mind because he knows that one day he’ll want to look back at this moment and remember how things were before he changed everything. To see what his world looked like before it crumbled around him.

“When I started writing it, and there were all these other issues in it, I realised there wasn’t the space to navigate that,” Ali explains. “So I left it out. But it’s something that I care deeply about. I think at some point, it is going to be in a book that I write. Because it’s important.”