You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Kate Elizabeth Russell talks about her debut novel exploring coercion and consent

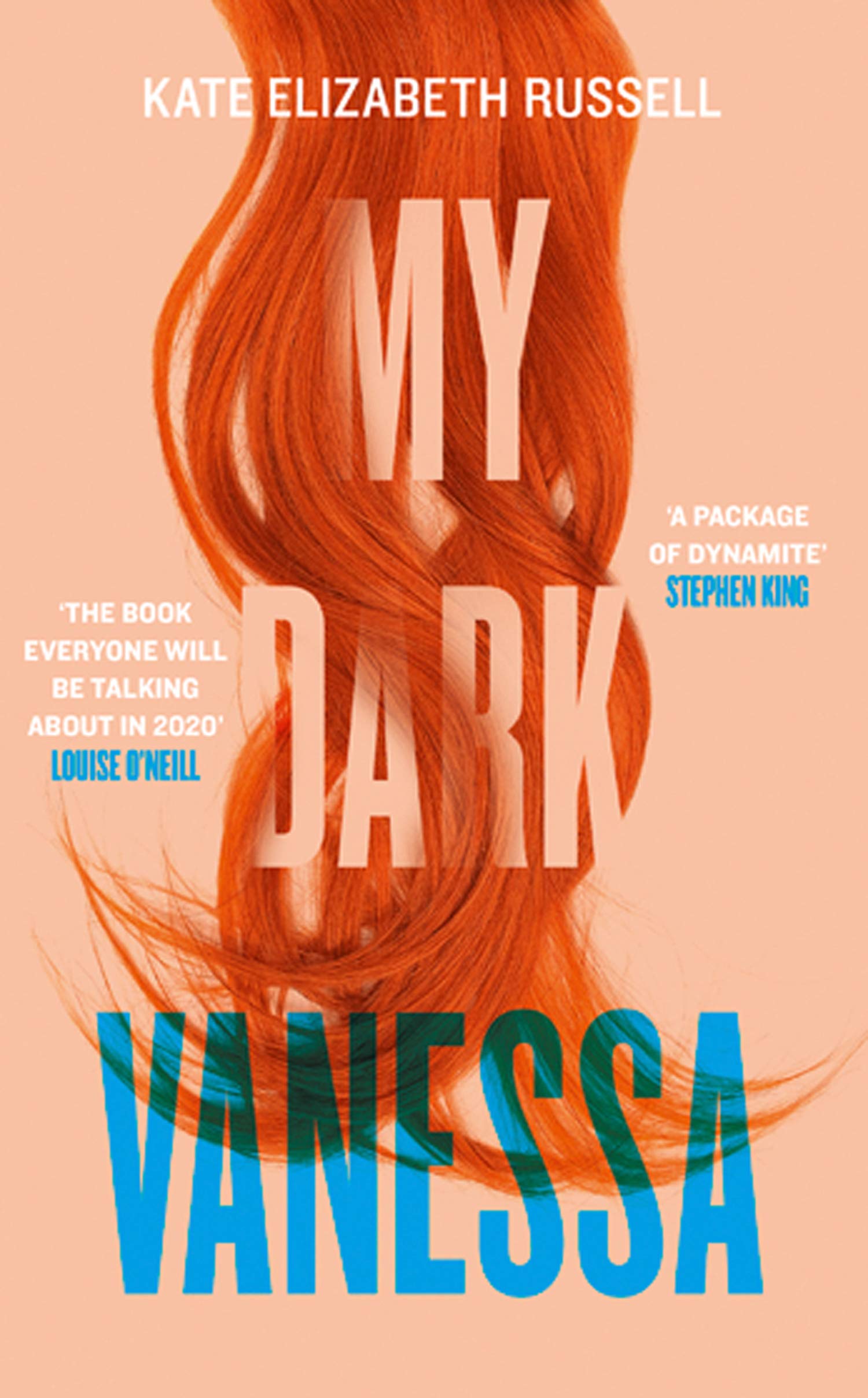

The first novel from Kate Elizabeth Russell has caused a stir on both sides of the Atlantic, and the literary tale of a teacher-student relationship lives up to the hype

Gut-wrenching. Riveting. Devastating. Just a few of the words that early readers of My Dark Vanessa have used to describe what is shaping up to be one of the début novels of 2020. Bought in a massive seven-figure pre-empt in the US, and for a six-figure pre-empt here by Fourth Estate, it tells of the sexual relationship between a 15-year-old girl and her 45-year-old high school English teacher. Every so often a novel arrives seemingly ripped from the headlines and My Dark Vanessa will be published in the turbulent wake of #MeToo and the sexual abuse scandals of Harvey Weinstein and Jeffrey Epstein. It is a strikingly well-written literary novel which grapples with issues of consent and coercion.

It opens in 2017 with 32-year-old Vanessa Wye learning that her high school English teacher, Jacob Strane, has been accused of sexual abuse by another former student of his. Vanessa is certain that her relationship with Strane wasn’t abusive, but loving. But the accusation will force Vanessa into a reckoning with her past, and the narrative she has told herself over and over during the intervening years—that Strane was the great love of her life.

If I had hated him completely it would have ended up as a much different novel!

The novel moves back in time to 2000 and we meet Vanessa as a bright, intellectually precocious teenager in her second year at Browick, an elite boarding school in Maine. Vanessa does not share the affluent background of her classmates, and she has fallen out with her closest friend over a boy, so she is already set apart from her peers. She is thrilled when her new English teacher appears to take a close interest in her. He comments on the poetry she has written and lends her books to read. One day, in the classroom beneath the desk, he presses his knee against her leg and things move rapidly from there. Before long she is spending nights at his house. What makes this such a chilling read is that the reader can see Strane’s actions for what they are: isolating and grooming a trusting young woman. But, crucially, the reader also sees the situation through teenage Vanessa’s eyes. She is made to feel special, chosen, and his attention is exhilarating.

A complex centre

When first-time author Kate Elizabeth Russell speaks to me over the phone from her home in Madison, Wisconsin, she explains that she wanted the novel to be a “layered experience, where you can understand Vanessa’s view of everything—as you’re getting it all through her first-person voice—but then there are these moments where Strane lets slip, through dialogue, how calculated he is in his attentions.” The reader sees Strane clearly as a sexual predator, but he is not a one-note villain. “I may be more sympathetic to him than most readers are—I had to be, because I was writing him. If I had hated him completely it would have ended up as a much different novel! To a certain degree I think that Strane believes that the relationship that they had was ‘real’, so I wanted to show these little slips, these little glimpses into his psyche that the reader would pick up on.”

I was working on the book every day, sometimes for 10 hours a day

The novel alternates between Vanessa’s present and her past. Her adult life is chaotic: she holds down a job as a hotel receptionist while getting as stoned as possible when she’s not working. It’s clear that her life, post-Strane, has not lived up to expectations and that the consequences of his abuse have stretched far beyond her time at school. When a journalist gets in touch to ask her to corroborate another student’s accusation, her life begins to unravel still further. It was while Russell was working on this central plotline that the whole #MeToo movement erupted. “I’d close my Word document and bring up social media, and it was like my novel was playing out in real time,” she says now.

It caused her some anxiety that her novel would be seen as “opportunistic” or capitalising on the scandal in some way, whereas she had, in fact, been working on it for years, “not constant work, but it was always there, something I was plugging away at”. At 16 she kept a journal, trying to make sense of her own experiences—although she is at pains to say My Dark Vanessa is not autobiographical—and developed the characters who would become Vanessa and Strane. Towards the end of her PhD in creative writing at the University of Kansas, she says, “I was working on the book every day, sometimes for 10 hours a day.” When the book was finished it took 66 query letters to find a literary agent, but once she finally did, it sold within 48 hours.

Russell is now 35, so I wonder how the novel changed over the years she was working on it? “The focus was always on this relationship between a girl and her teacher, from the very beginning, I always knew that was the core of the novel. In earlier versions I was more concerned with the idea of Strane being a tragic figure, the sort of Humbert Humbert idea of, ‘Oh, this poor man, he did wrong, but look at him suffer.’ But getting older, and coming into my own—both as a woman and as a writer—made me realise I didn’t have to write it that way. I could focus on Vanessa.”

On the subject of Humbert Humbert, My Dark Vanessa has been perceived by some as a 21st-century update of Nabokov’s 1955 novel Lolita—the book’s title is taken from a line in his 1962 novel Pale Fire—and Russell says that is not quite right: “It’s more that Vanessa is living in a world which is saturated with the Lolita trope.” Russell first read Lolita aged 14: “I love the novel deeply but it’s obviously so troubling at the same time. The way that it’s been used, and co-opted and misunderstood, I think, was on my mind throughout the entire writing process.”

Extract

When Strane and I met, I was 15 and he was 45, a perfect 30 years between us. That’s how I described the difference back then—perfect. I loved the math of it, how he was exactly three times my age, how easy it was to imagine three of me fitting inside him: one of me curled around his brain, another around his heart, the third turned to liquid and sliding through his veins.

At Browick, he said, teacher-student romances were known to happen from time to time, but he’d never had one because before me, he never had the desire. I was the first student who put the thought in his head. There was something about me that made it worth the risk. I had an allure that drew him in.

It wasn’t about how young I was, not for him. Above anything else, he loved my mind. He said I had genius-level emotional intelligence, that I wrote like a prodigy, that he could talk to me, confide in me. Lurking within me, he said, was a dark romanticism, the same kind housed within himself. No one had ever understood that dark part of him until I came along.

In a world where our understanding of abuse is changing almost week by week, to describe a pupil/teacher relationship—with its huge imbalance of power and control—as an “affair” now seems very wrong. Russell agrees: “I think when Vanessa uses that word to describe it, it’s almost aspirational in a way, like, ‘This is what I want it to have been.’ Because what other words exist? It wasn’t a relationship, and I don’t think Vanessa would use that word anyway. She’s not going to use words like ‘abuse’. So the words don’t exist. Which presents an interesting obstacle both for the character, and also for the writer: if the words don’t exist to describe what it is that you’re writing about, then how do you handle that?”