You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

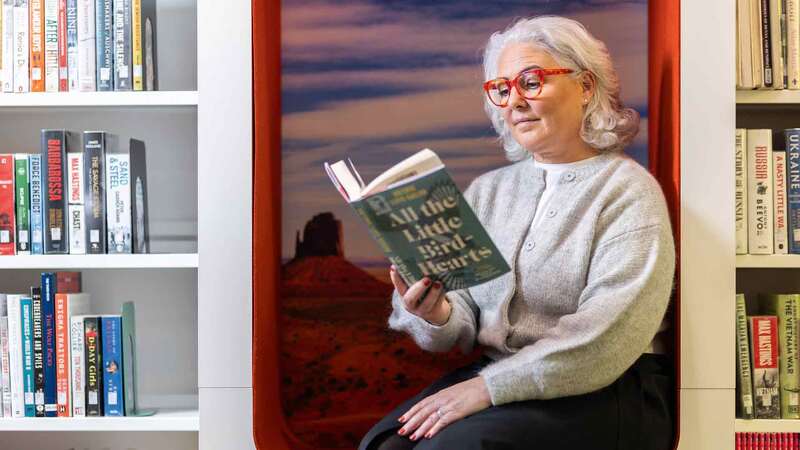

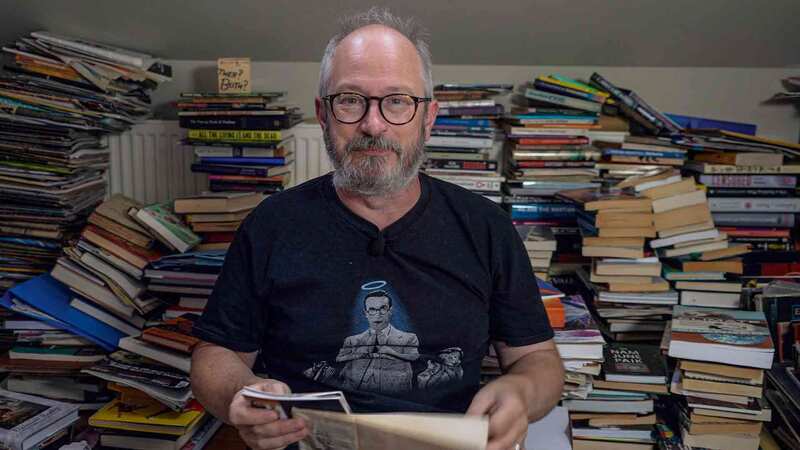

Kevin Maher | 'A high premium is placed on humour in Ireland; the craic is a big deal'

Kevin Maher describes himself as the “world’s laziest novelist.” Author of The Fields, the critically acclaimed coming-of-age novel set in 1980s Dublin, his follow-up novel is the story of Jay, a hapless young man from Ireland who arrives in London in the early Nineties. In Last Night on Earth (Little, Brown) Jay moves quickly, and in a blur of mistakes and mishaps, from the world of unskilled labouring to the glamorous and cocaine-fuelled roles of film critic and documentary maker and from a single, clueless man to a recently divorced, still clueless father of a difficult three-year-old.

Maher moved to London in the early 1990s, working as an unskilled labourer before moving into the world of television as a film reviewer for “The Big Breakfast”, film editor of The Face and a presenter on “Screen Time”, an Irish TV show about film. He says that, “as with The Fields, it is a really lazy exaggerated version of my own life. I know novelists that write based on their travels abroad and have research trips to find the muse but they are all monied and independently wealthy and it is a real bugbear of mine that I have to have a job. I have a job, I have a mortgage to pay, three children that suck up money. It fascinates me, the class element in writing. No one is really talking about it. It sounds like I’m really chippy about it, and I’m not, it’s just that some of us have mortgages to pay. Although I’m sure other authors that have those things as well would just tell me to get my shit together.”

If The Fields is a coming-of-age story, then Last Night on Earth is more a novel about a man ageing—perhaps not growing up, but definitely growing older. At the bleeding heart of the novel is the demise of Jay’s marriage to Shauna, in the wake of the difficult birth of their child Bonnie, as they both come to terms with the true realities of parenthood. Maher says that “being at the birth of a child is enough to blow your mind, and having a child puts enough of a strain on your relationship that you can imagine two people having a divorce because of it”.

At a point in the novel, Shauna tells her insalubrious and unconventional therapist Dr Ghert of the relief she felt when someone told her it was all right to occasionally want to “throw your baby out of the window”. Maher says he wanted to explore the truth behind the delicate emotional balance of being a parent.

“An NCT nurse actually said that to us and a lot of it was a reaction to things I had been reading. I was really annoyed about We Need To Talk About Kevin. I read it when we were on our second child and I got so angry because it was just a mis-selling of the story. There is a line down the middle: 50% of the time it’s really, really difficult and 50% of the time you’re ecstatic. I didn’t have an agenda, it was more of a subconscious thing. If you’re writing about the subject of parenthood in an even marginally honest way, you have to tell that side of the story: where you go from being an independent couple that goes for drinks and chats with friends to a person that basically serves and works for someone else. Sometimes it feels like you are almost in a perpetual sense of trauma.”

Mother country

In The Fields it is the relationship between teenage narrator Jim Finnegan and his father that fills the pages, but with his latest novel Maher wanted to explore the uniquely Irish tradition of the Irish Mammy. “Freud said something like ‘a boy that feels totally loved by his mother can handle anything’, and I wanted to write about that, and prod around in the sometime uncomfortable relationship between boys and their mothers, no matter how close they are. The Irish Mammy is a very real thing in Ireland. No one even blinked an eye when Daniel O’Donnell dedicated love songs to his mammy, it’s just one of those things.”

Set in the London of the 1990s, with Boyzone and D Ream on the radio, Tony Blair in power and the Millennium Dome slowly changing the skyline, Maher describes Last Night on Earth as his “dementia and postnatal depression” novel. “Writing about the ‘90s felt a bit like Alzheimer’s to me. It was quite sociable time for me, before I got married and had kids, so I went out a lot and there was a lot of drinking. Writing The Fields was very clear, I had a real pinpoint on the ‘80s, whereas London in the ‘90s is very hazy, so I had to make it non-chronological.”

He adds: “The only thing I did was loads of research on the Millennium Dome. I wasted hundreds of pounds on books on the Dome. I’m probably one of the world’s foremost experts on the Dome but, very kindly, my editor [Clare Smith at Little, Brown] cut everything on the Dome out of the book, all of the information about rivets and steel beams. It was that classic, crap amateur novelist thing of trying to show off everything you know, when you definitely don’t need to.”

A lot of laughs

Despite honing in on issues that are not often mined for humour—such as domestic abuse, infidelity and drug addition—in Last Night on Earth Maher writes with great comic precision, and is happy to gently and humorously prod at Catholicism and the new religion of the 21st century: therapy. Dr Ghert and the Dublin Fathers of Jay’s past give the novel some ridiculous, laugh-out-loud moments—including the idea that Jay is Jesus Christ returned to Earth.

Maher says: “Ireland is really secular now, but even secular people know a lot about religion and Catholicism—it seemed like a subject area that was just in the air. So weirdly to me, the idea that Jay is the Second Coming didn’t seem that ridiculous. I also spent a fair bit of time in Scotland, writing The Fields, and I spent time around therapists and new age healers . . . I’m always a little bit suspicious of them. The gender split where I was [staying] was something like 80 women to 20 men, and there were some really dodgy characters. Maybe it is a cowardly cynicism, but I’ve always been a bit skeptical of therapists. I’ve been to some good ones that I’ve loved, but with Dr Ghert I wanted him to be a tiny bit creepy and a bit of a horrible prat.”

I write all day for the Times, so when it comes to writing the book at 11 p.m., I just want to give myself a laugh

Maher describes comic writing as, “almost a means-of-production question”: “I write all day for the Times, so when it comes to writing the book at 11 p.m., I just want to give myself a laugh. My main goal when I’m writing is to give myself a break and a laugh. Life to a point is absurd, and it is funny. A high premium is placed on humour in Ireland—the craic is a big deal—and even from a young age I’ve been aware that even quite serious situations can be incredibly funny. It’s all about context.”

Maher is currently working on a third novel, which “is so much fun. It’s set in the modern day, which is a huge relief, among men in their 40s, and it is looking at men who have this big question mark as to their function. The characters are a bit more sympathetic, which makes it easier to write I guess. It’s a bit like Fight Club . . . but without the punching.”

Metadata

Publication 02.05.15

Formats HB, EB, PB

ISBN 9781408705070/ 9781408705094

Rights United Agents will be selling rights at this year’s London Book Fair

Editor Clare Smith

Agent Jim Gill,

United Agents