You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

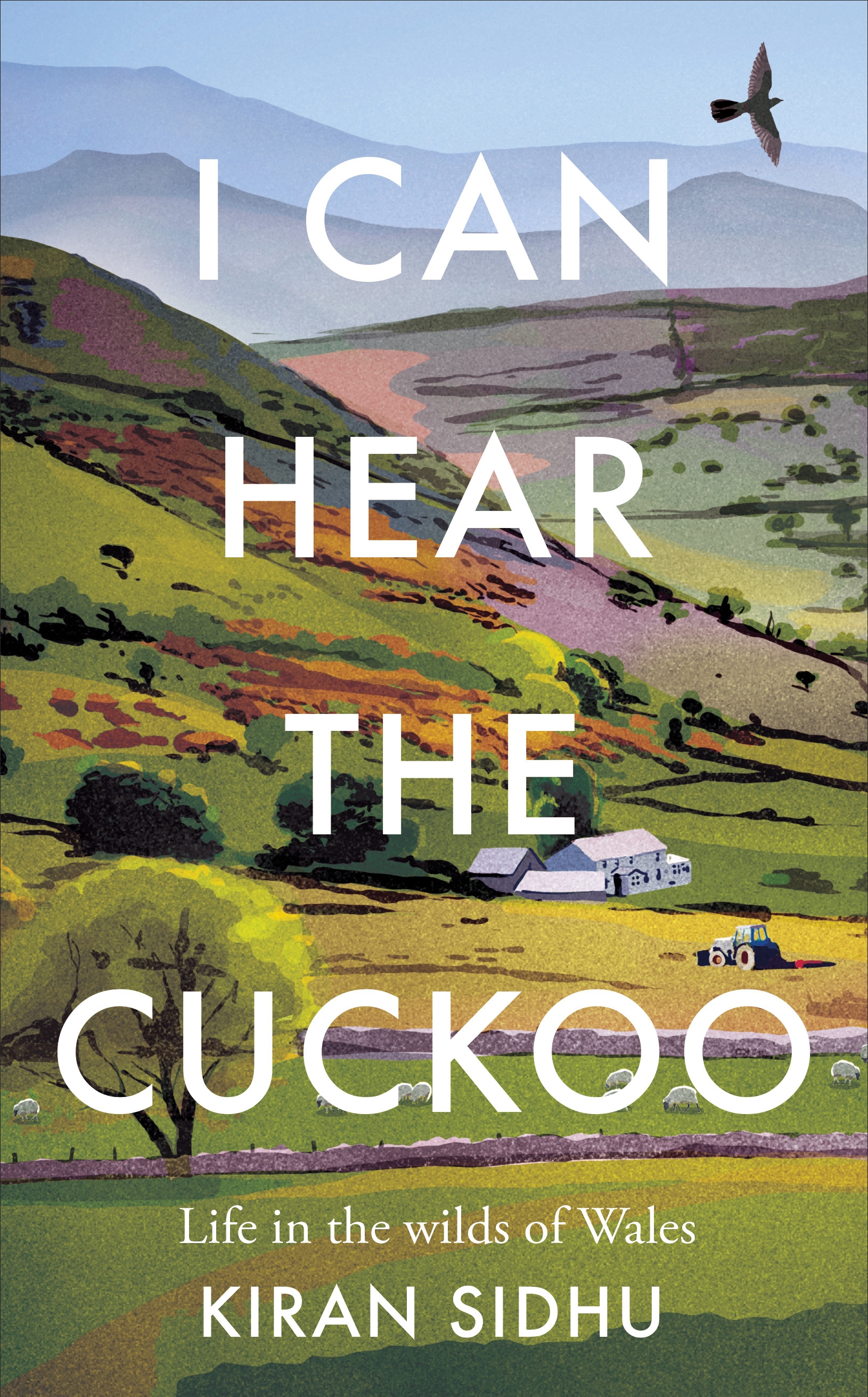

Kiran Sidhu on what the countryside can show us about life in her latest book

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

A move from London to a rural community brought Kiran Sidhu a whole new philosophy on life.

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

Poleaxed with grief after the death of her mother, and struggling with toxic family relationships that had erased her sense of self, freelance journalist Kiran Sidhu left London and settled with her husband in a remote valley in Ceredigion, west Wales, in 2020.

So a fairly conventional narrative, you might think, of life crisis prompting a shift from town to country. But what’s particularly striking about I Can Hear the Cuckoo: Life in the Wilds of Wales—Sidhu’s account of her move to west Wales—is the philosophical vein that runs through it. For it’s really about what living in a small rural community can teach us about life.

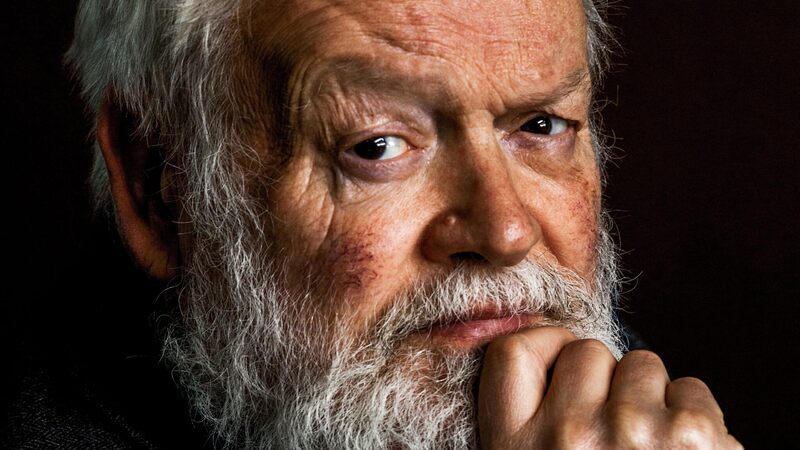

The story of how I Can Hear the Cuckoo came to be written is a remarkable one. In 2021, Sidhu—who studied philosophy at university—wrote an article for the Guardian about 73-year-old sheep farmer Wilf Davies. Born in the valley which he has scarcely left since, Wilf taught her that the cuckoo arrives in April. The article went viral. “It was crazy,” Sidhu tells me when we meet via Zoom. “The ‘Today Show’ were talking about it in America, and in the UK ‘This Morning’ wanted to interview Wilf. “I gained 500 new Twitter followers and four directors got in touch wanting to make a film.” A second article that focused on Sidhu’s friendship with Wilf also went viral, and resulted in her being contacted by agents and publishers proposing a book.

The film inspired by Sidhu’s article appeared last year. Entitled “Heart Valley” and directed by Christian Cargill, written by Sidhu and produced by Pulse Films, it won Best Documentary Short Film at the 2022 Tribeca Film Festival. For 19 glorious minutes it shows genial, thoughtful Wilf tending to his sheep, going about his farm duties, and for his customary evening walk as he talks about an unvarying routine that brings him a deep contentment, despite its challenges. “The valley has been made to the shape of my heart. Everything’s perfect,” he says.

“Wilf’s very existence intrigued me because he’s everything I’m not,” says Sidhu. “While we’re told that variety is the spice of life, here he was living in a very small world. And that challenged me and led me to some fundamental, philosophical questions about what it means to be happy.”

I wanted to know about the cows, I wanted to know about the pigs. I was curious. And people like that

While Wilf’s deceptively humdrum life also provides a leitmotif in I Can Hear the Cuckoo, the book is much broader in scope than the film, introducing us to other people in Sidhu’s close-knit home community. There’s Sarah who gets Sidhu sledging for the first time when the winter snow arrives; 70-year-old Jane who lives at the top of a mountain with three dogs, 10 geese and four alpacas, and is a dab hand at DIY; and Donna who teaches Sidhu how to trim goat hooves. Throughout the book, there are themes of rebirth and renewal and of respect for the rhythm and seasons of the earth.

The sense of belonging Sidhu finds in I Can Hear the Cuckoo is also tribute to her innate inquisitiveness about her valley home. “I wanted to know about the cows, I wanted to know about the pigs. I was curious. And people like that,” she tells me.

It can be brutal. Sometimes crows come and peck out the eyes of newborn lambs, and you see lorryloads of sheep going off to the abattoir. Life and death sit very closely together in the countryside

In the book, she tells how she chose to watch a farmer named Ernie slaughter her neighbour’s pigs. “I wanted that experience because I asked myself: why wouldn’t I watch it? I eat meat. So why should Ernie be the ogre because he’s doing the killing and I’m just doing the eating?” In this way, Sidhu never romanticises her rural life, nor does she shy away from the cruelties of nature in the raw. “It can be brutal. Sometimes crows come and peck out the eyes of newborn lambs, and you see lorryloads of sheep going off to the abattoir. Life and death sit very closely together in the countryside.” Counter-intuitively, this starkness helped Sidhu confront and move through her bereavement. “I never thought I’d ever write about the death of my mother because I was afraid to look at it. But the countryside teaches you that there’s a time to live, and a time to die.”

Ultimately, I Can Hear the Cuckoo is also a profound book about a community which thrives on the diversity of the people who live there. “Because Wilf is so different from me,” says Sidhu, “he has everything to teach me. Friendship can be born from mutual admiration, not just affinity. However different we may be, we share a valley here and that’s the thing that keeps us together.”