You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Laura Cumming in conversation about the glory of Dutch art

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

Observer art critic Laura Cumming on how great art can teach us to see the world in totally different ways.

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

"There’s a buoyancy in Dutch art and in the world it depicts. It’s energetic, it’s ebullient. It dries your tears.”

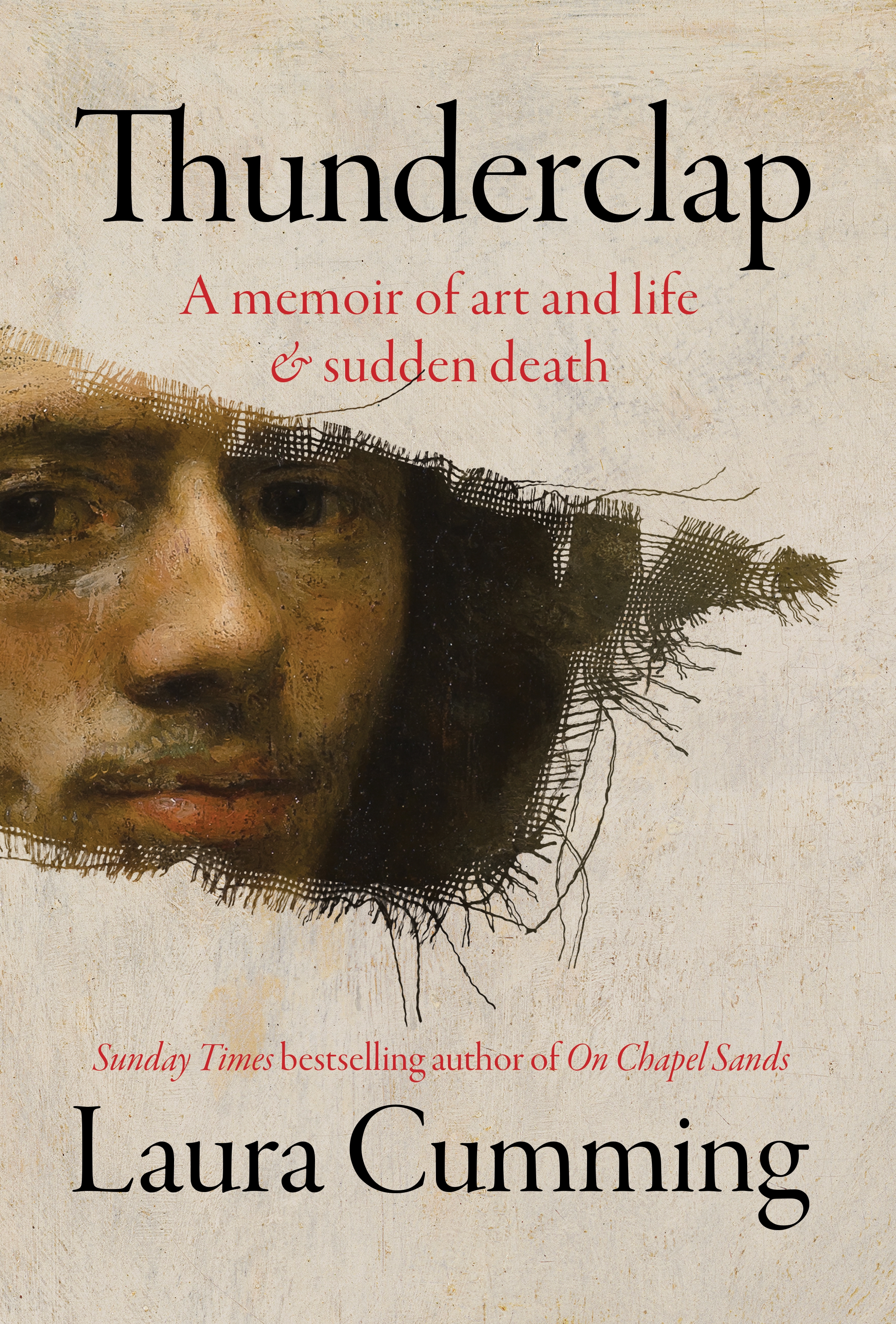

Over tea at the British Library, author and Observer art critic Laura Cumming is talking about her lifelong passion for the art of the Dutch Golden Age; a passion which infuses her forthcoming book, Thunderclap: A Memoir of Art and Life & Sudden Death. It’s a love she shared both with her mother—whom we met in Cumming’s last book, On Chapel Sands—and her father, Scottish artist James Cumming who taught her about colour, light and the rewards of looking closely, and to whom Thunderclap is, in part, a loving tribute.

“In On Chapel Sands, I wanted to see through my mother’s eyes. In this new one I wanted to see through his,” Cumming says. While quite different in subject matter, both books have Cumming’s spellbinding storytelling in common. Thunderclap is as deftly told as any thriller, culminating in a lightning strike of a final paragraph which makes the hairs stand up on the back of my neck each time I read it. It is also an astonishingly rich book about the glories that are revealed to us when we look at great paintings with careful attention, and an open heart. How a work of art can suddenly open our eyes in a thunderclap of clarity.

I suppose this is the miracle of art, and the nobility of those who make it: the transcending of all private suffering

It is partly its sheer ubiquity which endears Cumming to 17th-century Dutch art. “Go into any museum anywhere in this country and you will find a Dutch painting. There were more painters in the Dutch Golden Age, painting more paintings, than anywhere else in history. And with the rise of a new middle-class, they were painting for people like you and me, depicting the world in which they were living. That makes it an infinitely habitable world, and I feel as if I’ve been moving around inside it my whole life.” Even, she tells me, in lockdown when museums and galleries were out of bounds. “I have Dutch postcards all over my house, and they spoke to me from their domesticity to my domesticity in a way that no other art did. All those courtyards and streets, and doors that led into rooms that led into other rooms, were a huge solace because they gave me infinite other places to go.”

Dutch paintings shine from some of Cumming’s earliest memories too, including the postcards given to her during her Edinburgh childhood by a doctor as a reward for losing weight. “I’m eight years old and I’m being made to go on a diet and you might wonder about the psychological effect of that! Well, the effect was: it made me love Dutch art, because every time I lost a couple of pounds, I got a postcard of a Dutch painting.” Prior to that, there was a family trip to the Netherlands after her father received a small grant to study Dutch painting. That trip has burned bright in her memory ever since. “It was the only time we ever went anywhere abroad so it seemed like the most exotic place on earth to me. The design of lights, the flatness of the roads that had been dredged out of the sea, the great roundels of cheese.”

Cumming has revisited the museums and galleries of the Netherlands many times since, most recently to review the current blockbuster Vermeer exhibition at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum of which she wrote in her five-star review that it was a “near-perfect show”. If you love art history, Thunderclap will not disappoint. While such well-known names as Vermeer and Rembrandt do feature, Cumming is on a mission to acquaint people with the work of artists she regards as “tremendously overlooked”. These include the floodlit still lives of Adriaen Coorte; the humour-filled flower paintings of Rachel Ruysch; and the sunlit depictions of church interiors by Emmanuel de Witte, where, despite the artist’s life of poverty and utter misery, “everything is peace and beauty”. “I suppose,” Cumming writes, “this is the miracle of art, and the nobility of those who make it: the transcending of all private suffering.”

They paint to speak directly to us. And not just to our eyes but to our hearts

But the star turn in Thunderclap is an artist who is in Cumming’s eyes, “the most advanced and progressive of that time”: the elusive Carel Fabritius. Best known for his exquisite rendering of a goldfinch (the one that glows from the cover of Donna Tartt’s novel), tantalisingly few of his enigmatic paintings survive: only 13 confirmed artworks. Writing that “he cannot paint even so much as a side street in Delft without making it appear transfixingly strange”, Cumming illuminates what she finds extraordinary and precious about his work. Her father shared her sense of wonder. Standing before Fabritius’ portrait of silk merchant Abraham Potter on that early trip to the Netherlands, he made a note in his sketchbook—read much later with a thunderclap of recognition by his daughter—of being struck by its “modern eyes”.

“A View of Delft” which hangs in London’s National Gallery is perhaps Cumming’s best-loved Fabritius. In Thunderclap she describes how, as a young woman in her 20s, living in London and in the throes of a disastrous love affair, she would take refuge in front of it. “This tiny painting that nobody ever seems to notice shows a man in black sitting in the shadows. At the time, he seemed immutable, totally loyal, but also tremendously enigmatic and basically I had a crush on him. In time I stopped seeing the real man, but I carried on seeing the painted one.”

To this day, more is known about Fabritius in death than in life. On the morning of 12th October 1654, in his home town of Delft, a sudden explosion was followed by a thunderclap that could be heard more than 70 miles away. Everyone in the artist’s house was killed instantly by the blast which was caused by the igniting of an underground store of gunpowder. Fabritius died a few hours later of his injuries. He was 32.

Extract

My father’s art is a body of colour drawn through the mind and eye. I see him now, removing his glasses to renew his sight with his palms after the long studio night, leaving on the canvas a glory of cobalt, cerulean, gold, all the way to black and white and every yellow.

Seeing is everything. Looking is everything.

It was for him, it is for me. If I had no more speech, hearing or movement, I would still have the active life of looking; and the luxury of its replay in my dreams at night.

The insatiable longing is constantly and miraculously fulfilled; pure joy, total gratitude. And art increases this looking, gives you other eyes to see with, other ways of seeing, other visions of existence. Art and artists enlarge

our world.

What survives to this day of Fabritius, of all the Dutch artists she cherishes, and of her own beloved artist father who died of cancer in 1991, is Cumming’s enduring preoccupation. Ultimately Thunderclap is a book about the immediacy, the transcendency, the immortality of great art, by great artists who, asserts Cumming, don’t make art to be part of some long tradition as art historians would sometimes have us believe. “No, they paint to speak directly to us. And not just to our eyes but to our hearts.”