You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Laura Noakes, her début children's novel, subverting expectations and promoting representation

Charlotte Eyre

Charlotte EyreCharlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed ...more

Début author Laura Noakes’ action-packed novel set in Victorian London seeks to subvert expectations about what disabled children can do, making them the heroes of the story.

Charlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed ...more

Laura Noakes was studying for a PhD in legal history when she fell down a “rabbit hole” of looking at how disabled children were institutionalised during the Victorian era.

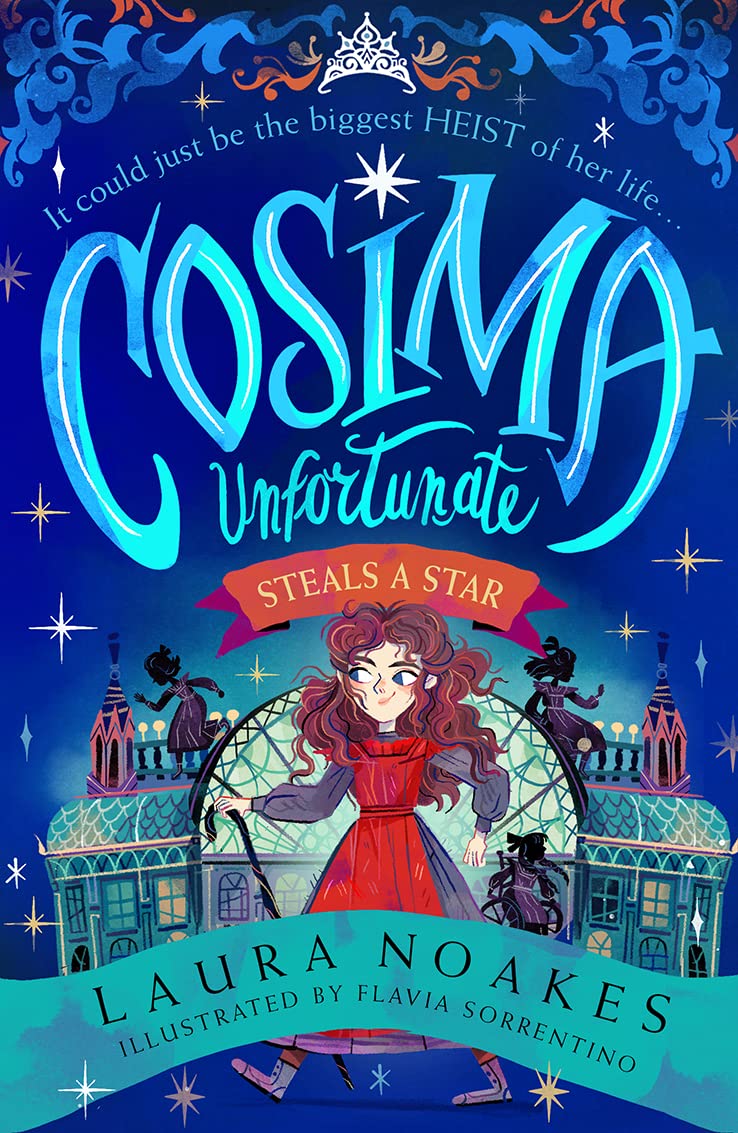

“I immediately thought ‘that’s a good story’,” says the début author, whose historical heist novel Cosima Unfortunate Steals a Star, out in May, features not just one but a whole group of children with disabilities. And this isn’t a novel designed to make you feel sorry for Cosima and her group of friends, who are all dynamic and brilliant, using their wits and skills to outwit one of the most powerful aristocrats of the time.

The year is 1899 and Cosima, Pearl, Mary and Diya live at the Home for Unfortunate Girls in Kensington, London. When they are visited by Lord Francis Fitzroy, the man behind the upcoming Empire Exhibition, they decide to pull off their biggest heist to date and steal the legendary Star Diamond of India.

A lot of the problems with being disabled aren’t because of the disability itself. A lot of it is about accessibility

Cosima, like her creator, has hypermobility, and Noakes says she always gravitates towards writing characters who have the same disability as her. She also wants to show what disabled children can do. “Even now, the most surprising story to feature a group of disabled kids is a heist,” she says. “It’s very action-packed. I thought that would be the best way to kind of subvert expectations.”

The other girls have different disabilities—one has anxiety, another uses a wheelchair—and some of the most exciting bits of the story are when, at points in the plot where it looks like they are about to get caught, they come up with an invention just in time, like a winch made by Diya to bypass some stairs.

“A lot of the problems with being disabled aren’t because of the disability itself. A lot of it is about accessibility. Like when you turn up to train stations and you can’t get over the bridge,” says Noakes. “Disabled people and people who are chronically ill constantly have to have a plan B in the back of their head. Innovation is quite innate when the world isn’t built for you.”

As well as the Home, a lot of other historical research crept into the book. The girls are helped by a fabulously feminist journalist called Aggie, who is based on Nellie Bly, famous for going undercover to expose conditions in mental institutions. And why send the girls off to an exhibition all about empire? That was based on the Great Exhibition of 1851, where there really was a famous diamond—the Koh-i-noor—on display.

It’s so important to capture how people experience disability and chronic illness in different ways

The Koh-i-noor is currently part of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom but is regarded by many as colonial loot, and there was a “real message that went all the way through the Great Exhibition that was pro-colonialism”, says the author. “I wanted to subvert that… You can still see the legacy today in the British Museum. I come from a small town and a lot of people don’t know about the realities of empire. We are not taught about it in school.”

Gaining momentum

Noakes started writing Cosima’s story in June 2020, towards the end of the first Covid-19 lockdown. But a real turning point in the book’s creation was when she was accepted onto the WriteMentor summer programme, where one of her mentors was author Maz Evans.

“She gave me so much confidence and that’s what transformed it, really. Over a year I had constant feedback and I was just chipping away at it,” she says.

I want disabled children and readers to see themselves as heroes in their own stories. They’re not just there to put a plot point forward or to be some kind of inspiration

Her New Year’s resolution last year was to query publishers (expecting the process to take at least six months) but it is at this point in Noakes’ story that things start to move really fast. Lydia Silver at the Darley Anderson Children’s Book Agency made an offer within a week and the book went out on submission in March. There was then an auction and HarperCollins acquired world language rights, which was “gobsmacking”, she says. “We were in Glasgow for my birthday when I got an email from Lydia saying that HarperCollins were interested. I kept wandering around and bumping into people in Primark.”

Disabled heroes

Noakes is full of praise for the care taken by HarperCollins over how she will do promotional events and how they can accommodate her disability in, for example, schools. Disabled people are often made to feel like they are “a bit of a problem” in the workplace, Noakes says, but she is keen to stress that her foray into publishing has been the opposite. The team at HarperCollins has been “amazing”.

She has also noticed the push in publishing for more books by disabled authors and illustrators, singling out authors like Lisette Auton, whose début The Secret of Haven Point (Penguin Random House) was released in February last year.

“It’s really heartening to see. There are so many people with disabilities and there are so many different disabilities. It’s so important to capture how people experience disability and chronic illness in different ways. And it does seem like there’s a push towards more disabled characters being written by disabled authors, which is great in my opinion.”

Noakes’ contract was for two titles and at the end of Cosima Unfortunate Steals a Star someone from the heroine’s early childhood comes to find her, setting up the story nicely for book two, but Noakes says she would be open to writing more books in the series.

Extract

Cosima pressed her face against the frost covered window of the ground floor of the Home for Unfortunate Girls, her breath fogging up the glass. She could just about make out a shadowed figure striding purposefully towards the front door. Muffled sounds drifted through the flimsy walls, and Cos caught the swoosh as Miss Stain welcomed in the mysterious guest from the snowstorm outside. The well-to-do ladies Miss Stain had invited round for tea weren’t due for hours yet.

Footsteps thundered towards the schoolroom.

‘Mr Stain is coming,’ Cos hissed to the others. ‘Hide everything!’

As fast as she possibly could Cos creaked herself upright, her joints performing a cacophony of painful clicks. Activity buzzed through the schoolroom as maps were torn down from the wall, contraband items hidden hastily under loose floorboards, and Diya shoved her half-finished invention into the cupboard.

Cos grabbed her walking stick, made from an old broom Diya had found in the back of a cobweb covered closet, and limped across the groaning floor.

She sat with a thud on a cramped school desk just as a peephole, embedded in the door, opened. A beady eye peered inside, glaring at the children.

But for now, what does she hope readers gain from book one? “I want disabled children and readers to see themselves as heroes in their own stories. They’re not just there to put a plot point forward or to be some kind of inspiration. They have agency and they are able to be the drivers of their own stories,” she says. “For non-disabled readers, I want them to understand that disabled people can be heroes. There are challenges with being disabled but really we’re just normal people.”