You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Leo Vardiashvili in conversation about his debut novel, a tale of family, war and loss

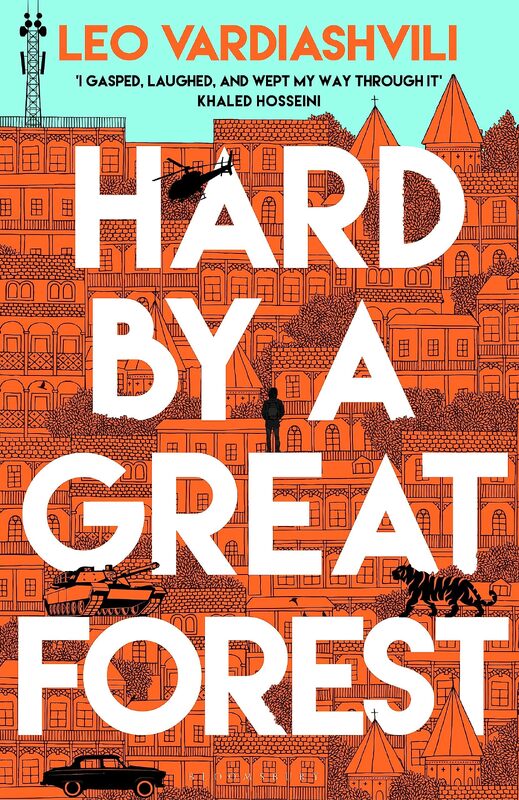

Bloomsbury’s lead literary début for 2024 is a multifaceted tale of a family torn apart by war, by Tbilisi-born Leo Vardiashvili.

Bloomsbury’s lead literary début for 2024 is a rich, densely layered novel which manages to be several books in one: a picaresque adventure story, an intimate account of a family torn apart by war, and a tale powered by a central, propulsive mystery—that of a father who has gone missing on a trip back to his home country. It is also wildly funny and piercingly sad, often on the same page.

Hard By a Great Forest is narrated by Saba and by the end of the first page we know the bones of the story to come. “See, war trumps most things. You’ll find that a volley of AK-47 rounds fired right down your street will override almost any other concern.” When Saba was eight and his brother Sandro two years older, the family managed to flee Tbilisi, which had descended into the chaos of civil war after Georgia broke away from the Soviet Union in 1991. With their dad, Irakli, the brothers arrived in London as refugees, but their mother, Eka, stayed behind.

Now, after two decades in the UK, Irakli has returned to his still shattered homeland to find Eka. But within weeks he disappears, after sending a last email: “My boys, I did something I can’t undo. I need to get away from here before those people catch me. Maybe in the mountains I’ll be safe. I left a trail I can’t erase. Do not follow it.”

The theme of going back home to find it different is from my own life

Saba abandons his life in London and flies to Tbilisi, running into trouble almost immediately when his passport is confiscated at the airport. He is rescued by Nodar, the mouthy driver of a decrepit Soviet-era taxi. Saba ends up staying in Nodar’s flat and, as Nodar drives him around the city he vaguely remembers from childhood, on the trail of the missing Irakli, it transpires that the taxi driver is himself an exile, from South Ossetia, the breakaway region of Georgia that has recently been occupied by Russia. Hard By a Great Forest goes to some dark places and some passages are distressing to read but the story is leavened by humour, particularly the exchanges between Saba and Nodar, and the hospitality of the ordinary people Saba encounters along the way (“A guest is a gift from God”, he is told).

Autobiographical elements

First novels are often assumed to be strongly autobiographical—which is not always the case, of course—but author Leo Vardiashvili’s early life shares some similarities to Saba’s. Born and raised in Tbilisi, Vardiashvili came to London with his family in 1995 as a 12-year-old refugee. Nearly 20 years passed before he returned to Georgia again, and memories of that trip were an influence on the novel, he says when we meet at his publisher’s offices in central London.

“The theme of going back home to find it different is from my own life,” he says, “and there are some anecdotes from the characters in the book that are lifted from my own life. But for the most part I was very conscious of making it not just a story about my family because no one wants to read that. At least, that’s what I thought when I was writing it.”

Vardiashvili always wanted to be a writer, he says. After arriving in the UK he started at a north London comprehensive in Year 8 and remembers sitting at the back of the class, dictionary in hand, struggling to understand a word. By Year 9 he was writing essays in English for homework with ease. Later, he read English Literature at Queen Mary University of London in Mile End. He wrote lots of short stories and sent them to “random online journals that you’ve never heard of and no longer exist. One of them got published, I’ve got a copy somewhere, they misspelled my name…”

Although he felt the need to establish a career (he is now a tax advisor for Ernst & Young) as “the starving artist thing” was not an option, he was always writing, “working towards something”.

That kind of sums it up, it doesn’t matter [who is doing the shelling], you’re destroying things, you’re hurting people’s families

In 2015 a news story from Georgia hit the international headlines: a great flood washed away the city’s zoo and led to the animals wandering the streets of Tbilisi. It was the prompt he needed to begin what would become Hard By a Great Forest (one of the escaped zoo animals makes a memorable appearance).

The novel took him six or so years to write, around the day job, “from 6 p.m. until falling asleep, and weekends”. He sent the finished manuscript to his agent in February 2022, and one month later she took it to the London Book Fair. It subsequently sold to Bloomsbury in an overnight pre-empt and in 14 territories, including Georgia, which Vardiashvili is particularly happy about as it means his relatives will be able to read it.

Keeping it in the family

Hard By a Great Forest is a novel about Georgia which illuminates the country’s troubled post-Soviet past and the deep trauma of war, but it is at heart the story of a family. “I tried to keep politics as much out of the book as possible,” says Vardiashvili. “There’s a conversation towards the end of the novel between Saba and Nodar where they are talking about the shelling of South Ossetia. I think it’s Nodar who says: ‘It’s a shell, it kills anyway, it doesn’t matter where it came from. I don’t care if it’s the Russians or Georgians.’ And that kind of sums it up, it doesn’t matter [who is doing the shelling], you’re destroying things, you’re hurting people’s families.”

Vardiashvili also wanted to explore “the refugee experience, the stuff that you don’t read about in the history books. It doesn’t really get mentioned, the kind of family-level trauma that happens where you’ve lost a grandma and you never get to see her again. I think that is consistent in any war.”

Extract

Where’s Eka?” We must have asked a thousand times.

Our mother stayed so we could escape. See, war trumps most things. You’ll find that a volley of AK‑47 rounds fired right down your street will override almost any other concern. We heard gunfire by night and saw brass twinkling on the pavement in the morning, as though it had rained shell casings all over Tbilisi. Sounds manageable so far.

But when a stray tank shell breaks the sound barrier by your bedroom window, screams on, and deletes the corner grocery shop and the entire family living above it, you’ll begin to make plans. Our parents, Irakli and Eka, made plans to get us all out, divorce be damned.

Getting out of the country meant shady bribes, stolen travel stamps, and counterfeit certificates. What money the family scratched together was barely enough for one parent and us children. Eka didn’t even have a passport. Together we couldn’t leave the country.

Meanwhile, the civil war was warming up, bullet holes in familiar places and people no longer a surprise. We had to go. Eka stayed and we escaped with Irakli.

That’s how we became motherless, Sandro and I. I was eight and Sandro was two years older. At that age, the difference was a whole ocean of experience.

“My favourite books are those that make me feel something,” he says, citing Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in particular - "So that’s what I was aiming for.” Later, he adds: “If at any point reading [my] book you cry, or nearly cry, or laugh out loud, that’s gold to me. That’s all I want: for it to be entertaining and for people to feel something real. And maybe get to know Georgia a little bit as well.”