You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

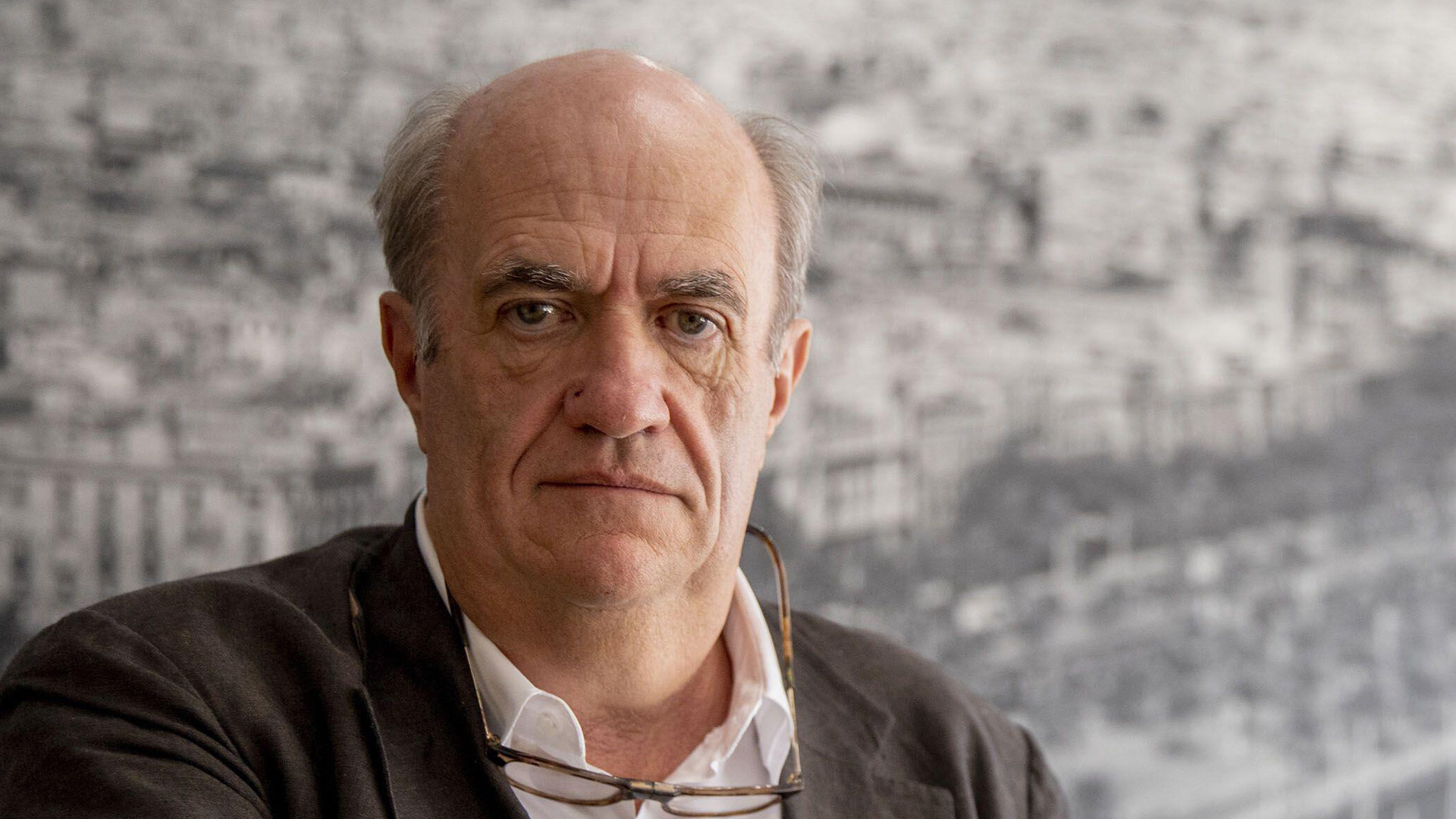

Long Ireland: Colm Tóibín on going back to Brooklyn and his return to Picador after 14 years

Colm Tóibín trundles into the Zoom an apologetic 15 minutes late. There has been a little kerfuffle with the time zone, as he is in the Catalan Pyrenees where he has had a home for 30 years.

No matter, he can be forgiven for Tóibín is hard at work, knee deep in the proofs of the Brooklyn sequel Long Island. Brooklyn is Tóibín’s greatest success commercially, shifting nearly 300,000 copies through Nielsen BookScan in the UK for £2.1m since its 2009 release, boosted by the 2015 film adaptation starring Saoirse Ronan.

The former journalist anticipates my obvious first question: why a sequel? He says: “The answer is, why not? The other answer is that there are very good reasons not. I mean, leave it alone – why interfere with people’s imaginations about what happens to the characters? Also, and this is not true for Hilary Mantel or ‘The Godfather’, but in general sequels tend to be pale.”

So Tóibín had resolutely dismissed revisiting Enniscorthy emigrée Eilis Lacey and her Italian-American beau Tony Fiorello’s story until “I got an idea walking down the street. And it came from nowhere. And it was an image. And it was a scene. And it was drama. I realised if I started with that – instead of taking up from Brooklyn as though you’re reading the same book – I would have something in the first three pages that would really require the reader and me to get going and think, ‘If you put this at the beginning, what next?’”

That beginning is so explosive it is under wraps at the moment, but what Tóibín can say is that the action has moved from the 1950s to the 1970s with Eilis and Tony, echoing the journey of many first or second-generation Americans’ immigrant experience, leaving the city for the titular suburbs. Tóibín says: “This isn’t glamorous The Great Gatsby Long Island – it’s absolutely suburban. People have nice gardens, it’s where you bring up your children. But it is very enclosed and Eilis has married an Italian so she has no friends, no cousins, no brothers. She’s isolated in the sense that she’s not part of an Irish community: no Irish dances, no Irish priests, no Irish boarding houses.”

A few years ago, Pulitzer winner Richard Russo came out with Everybody’s Fool, his sequel after a decade and a half to his hit Nobody’s Fool. He said that when writing the follow-up he couldn’t get Paul Newman – who played main character Sully in the Nobody’s Fool film adaptation – out of his head, so he gave up and the second book was in some ways a Newman-isation. Along a similar vein, I ask Tóibín if he was able to keep “Brooklyn” out of Long Island.

He ponders. “Not with Saoirse, as she played Eilis of an age; a woman 25 years later is very different. But Domhnall Gleeson, [as Jim, Eilis’ other suitor], was interesting. He played him as the sort of Irishman you never see in films or, indeed, novels: a man who doesn’t drink much, isn’t violent, is a quiet fellow who can be trusted. I told Domhnall he played a part without much precedent. It’s so easy to play the big, shouting Irishman, but we all have experiences of places where men are generally very quiet.”

An itinerant writer

There is another sequel of sorts for Tóibín as Long Island marks a move back to Picador after 14 years and eight books at Viking, following long-time editor Mary Mount’s return to run the imprint. Tóibín explains he likes

continuity and “the family”: his first editor at Picador before Mount was his now agent of 20 years, RCW’s Peter Straus; he has been collaborating with his US editor, Scribner senior vice-president and publisher Nan Graham, since 1998.

It’s so easy to play the big, shouting Irishman, but we all have experiences of places where men are generally very quiet

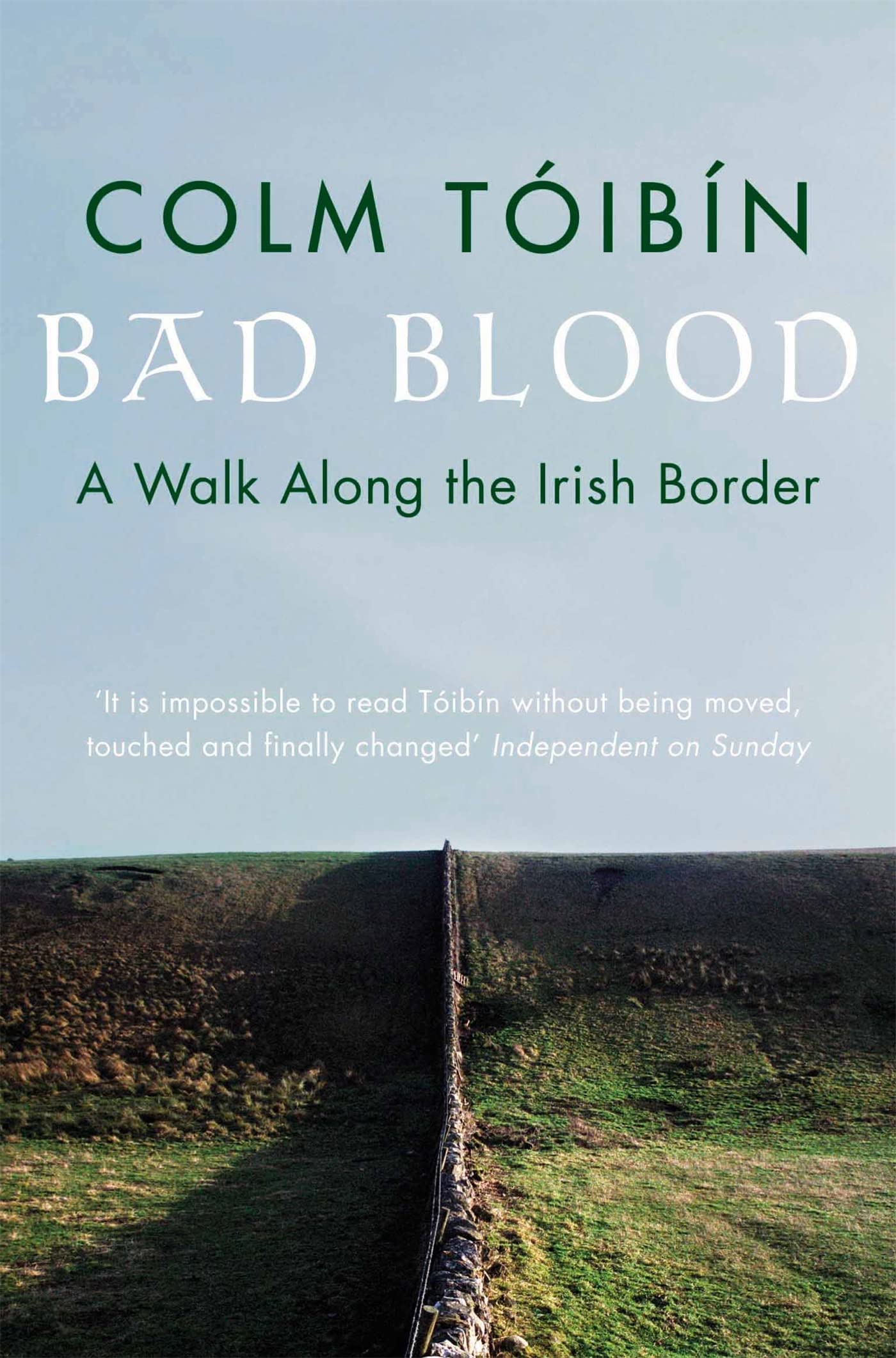

Just ahead of Long Island’s publication, Pan Mac will release the six-strong backlist of Tóibín’s previous Picador novels with a consistent series look, designed by Daisy Dickeson. These range from his 1990 début, The South – first published by Serpent’s Tail, though Picador later bought the rights – set like a number of his books in and around Tóibín’s home town of Enniscorthy, County Wexford; to The Blackwater Lightship, arguably his first ascension to the literary stratosphere with its 1999 Booker shortlisting; and The Master, his reimagination of Henry James’ life, which won the 2006 International Dublin Literary Award.

The Pyrenees is just one place Tóibín hangs his hat. For a good portion of the year he is in Los Angeles with his partner of 12 years, Hedi El Kholti, who co-edits the high literary press Semiotext(e). Plus there is time in New York, where he is a professor in Columbia University’s English department and back home to Ireland, often on duty as the Laureate for Irish Fiction, a post he has held since last year. In fact, he is away to Dublin a couple of days after we speak to begin a series of events with writers including Kevin Power, Aingeala Flannery and Joseph O’Connor.

A couple of eyebrows might have been raised when Tóibín accepted the laureateship as it is Arts Council Ireland-funded and Tóibín had publicly roasted the organisation a couple of years previously for its plans to cut some writers’ grants. He shrugs: “It’s a great thing, democracy. I was really, really concerned with what they were doing and had to make myself very clear. But I don’t think anyone on the Arts Council thought it was personal. We should be able to argue with them about what they are doing without the threat of cutting off all support for life. If not, it’s Russia.”

It’s a great thing, democracy. I was really, really concerned with what [the Arts Council] were doing and had to make myself very clear

But he took the laureate post because “I wanted to get involved. There are things that matter to me and one

of them is the relationship between libraries, readers and communities. The second one is the idea of a reading community. The idea is that this is very rich in Ireland, but it still has to be nurtured”. Plus, Tóibín says: “It takes a lot of time, but I get to talk with Naoise Dolan or to take a trip to Letterkenny in County Donegal to do an event with Luke Cassidy about his book, Iron Annie. I mean, these are the exciting things I want to do.”

Staying at home

A lot of those laureateship events are with the early career authors. That many are based at home and have not pursued their craft abroad, like many from Tóibín’s and previous generations, pleases him: “You don’t hear people saying, ‘Oh, in order to write I have to live in Paris.’

And there are very few Irish writers in London now. So Ireland has become a more comfortable place for writers – despite the fact that it’s incredibly expensive.”

Part of that staying at home might derive from Ireland’s social liberalisation over the past 20 years. Tóibín has welcomed this, but says the country is at an interesting point: “When I was working as a journalist in the 1970s and 1980s it was clear that the two impediments to progress in Ireland were the power of the Catholic Church and the IRA. And not just the IRA as an organisation but the ideology and tribalism around it. Once we dismantled those, the third pillar – equality – would come.”

But there has been a slowing down on equality, he says, by a government frozen on how to progress on issues relating to social and economic justice. “And the solution to this,” he goes on, “is a complete change of ideology in relation to what the state has to do, a different sort of politics. The problem for me is, the only one offering that solution is Sinn Féin. And my memory is too long, I’m too old, my stomach isn’t strong enough to vote for them. So I’m stuck.”