You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Louise O'Neill on changing the traditional fairy tale script

Caroline Carpenter

Caroline CarpenterCaroline is deputy features editor at The Bookseller and chair of the YA Book Prize, as well as being a co-host of children's book radio ...more

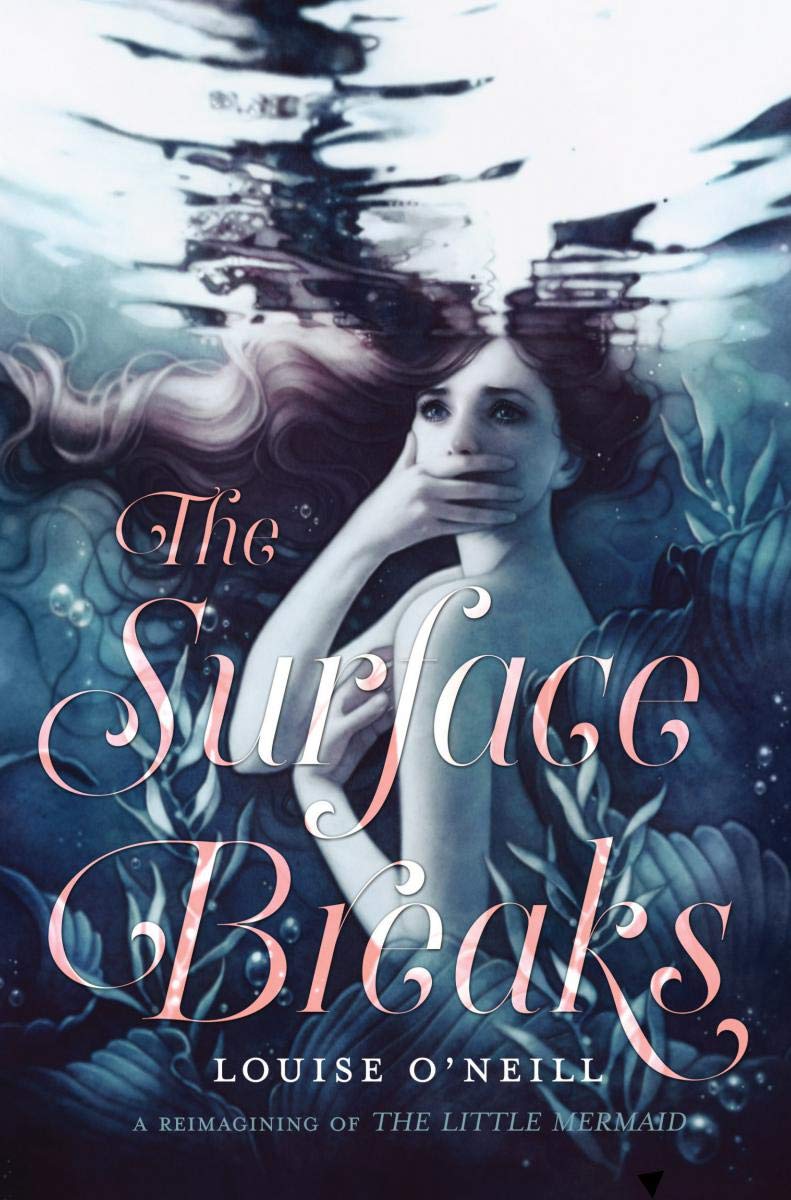

The Little Mermaid gets a feminist revamp in this thoroughly modern fairytale for the Trump era

Caroline is deputy features editor at The Bookseller and chair of the YA Book Prize, as well as being a co-host of children's book radio ...more

Prize-winning author Louise O’Neill was “knee-deep” in writing her first adult novel, Almost Love, in the summer of 2016 when Scholastic editor Lauren Fortune approached her about writing a feminist YA interpretation of The Little Mermaid. O’Neill says her first instinct was that she “should say no”, but she was hesitant to do so. She explains: “I’ve always loved this particular fairytale and felt an affinity with the little mermaid, and I felt like I would’ve really regretted it if I said no. So I said yes and took on the marvellous task of writing two books in one year.”

After finishing a first draft of Almost Love (out with riverrun in March) on a Thursday, she began penning The Surface Breaks (Scholastic, May)—a lyrical, modern retelling of the classic Hans Christian Andersen fairytale, set off the Irish coast—on the following Monday. She likens the process of writing them so close together to eating an incredible meal and feeling full, until dessert appears and you find room for more. Although it was coincidental, in retrospect O’Neill recognises that the two books share several similarities, including central female characters whose mothers have died, as well as themes around the silencing of women in relationships and the ways in which society encourages women to fulfil traditionally held aspirations. Ironically, the protagonist of Almost Love is obsessed with the sea, while O’Neill’s little mermaid, Gaia, is fascinated by life on land (her name means “of the earth”).

Under the sea

After producing two contemporary novels, Almost Love and, prior to that, YA title Asking For It, O’Neill found writing fantasy was “really fun” and a chance to let her imagination “run riot”. The 1989 animated Disney film of "The Little Mermaid" is perhaps the most widely known version of the story, but O’Neill chose to remain fairly faithful to the bleaker fairytale in her retelling, as it better suited her tendency to “skew slightly towards the darker side of life” in her writing. While the existing story arc was helpful when it came to plotting, she was keen to put her own twist on the tale, saying: “I wanted to honour the original fairytale but be much more empowering and fierce.”

A perfect representation of a patriarchal society, in which men are valued for their strength and their bravery, whereas women are valued for their physical attractiveness

The Surface Breaks is a vividly imagined portrayal of a magical underwater world of mer-folk and pearls, with the self-sacrifice of women at its heart. Like the original, it begins with the 15th birthday of the youngest and most beautiful of the Sea King’s six daughters. Turning 15 means Gaia can finally take her long-awaited first trip up to the surface of the ocean. There, she sees and falls in love with a young man and pins her hopes of escaping her restrictive life below on him.

O’Neill was eager to give her little mermaid more agency than she has had in previous incarnations. “I didn’t want to see her as passive or a victim; she’s just a girl who wants more than the world she grew up in thinks she is capable or worthy of. I wanted her to be more complex, someone who is just trying to survive, like all of us are.” Gaia has to contend with living in an underwater world that O’Neill describes as “a perfect representation of a patriarchal society, in which men are valued for their strength and their bravery, whereas women are valued for their physical attractiveness.” With her mother gone, Gaia’s entire life has been controlled by her father, including her imminent arranged marriage to a much older warrior mer-man.

The Sea King—who at one point says to Gaia’s betrothed: “If she were not my daughter, perhaps I would’ve chosen her for myself”—is “basically a stand-in for the patriarchy”, and O’Neill admits that her writing was “very inspired” by the US under Donald Trump and “the attempts to divide and ‘other’ people, and how dangerous that is”. The mer-folk share their world with the Russalkas (women who transformed into vengeful water nymphs following their tragic deaths) who have been banished to the murky Outerlands, where they are led by the Sea Witch, Ceto. She is another character that O’Neill wanted to reclaim.

The idea of the prince as saviour is very common in fairytales, and something I’m really interested in. It’s unrealistic and dangerous

She says: “There are a lot of problematic aspects of fairytales, and women tend to be divided into two categories: the good and the bad girls. For me, it was about exploring the fact that women contain multitudes. It smacks of sexism and ageism that in fairytales, the only thing that a single woman can be if she’s older is an evil, jealous crone.” Instead, O’Neill’s Sea Witch is “fascinating and sexy and comfortable in her own skin”. The author says: “She has chosen her own path in this world in which women are expected to do exactly what they’re told. I loved writing her scenes. I wanted her to be the most compelling character.”

A new prince

The figure of the prince in the original story also gains depth in this retelling. Privileged and handsome, Oliver is coping with the grief of losing his father a few years earlier, as well as the recent deaths of his close friends and girlfriend at sea. O’Neill explains: “He isn’t in a place emotionally to give Gaia what she needs but she’s convinced herself, because she feels so trapped in her own world, that he is her ticket out of there. The idea of the prince as saviour is very common in fairytales, and something I’m really interested in. It’s unrealistic and dangerous, and that’s something I hope to encourage young women to think more critically about.” Oliver’s resentful attitude towards his hard-working, ambitious mother also highlights to Gaia that life for women above the surface might not be quite as far removed from the Sea Kingdom as she had hoped.

O’Neill is currently working on a short story for an anthology, as well as preparing for the publication of Almost Love and The Surface Breaks, and a stage version of Asking For It, which is casting performers now and will premiere in June. She plans to take a break from writing novels until next year, although she already has a few ideas she wants to explore, and is interested in writing a play or TV screenplay. Whatever O’Neill tackles next, it is likely that, as with her work to date, it will interrogate patriarchal norms—something she says she “can’t seem to get away from” because it “pervades every part of life”—and contain her trademark cynical approach.

When I ask if she thinks she’ll ever write something happy, she laughs. She says: “I actually am generally very happy and positive. I’m always trying to look for the silver lining, and then as soon as I sit down to write, it just comes out really bleak. I would love to think that I was capable of writing something happy . . . Watch this space!”