You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Luke Kennard on his second novel, The Answer to Everything

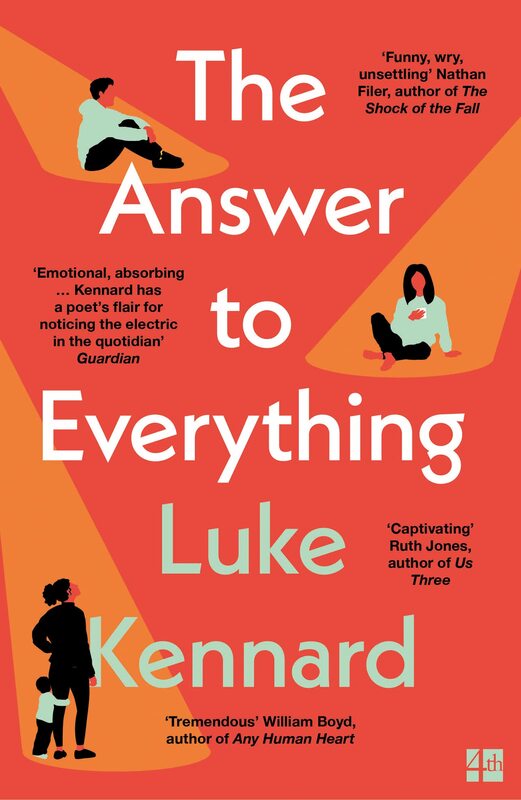

The second novel by acclaimed poet Luke Kennard is a sharply observed and often comic tale of dangerous midlife liaisons.

Luke Kennard arrives on Zoom looking slightly flustered: he has been teaching a poetry workshop to third-years at the University of Birmingham, and it’s only just finished. “It’s good to be on campus again. The only good thing about teaching on Zoom is that you immediately know everyone’s name,” he says. “But I’m so sorry to have kept you waiting.”

Kennard, who has kept me waiting for all of two minutes, is head of Birmingham’s department of film and creative writing. He’s also an award-winning poet: earlier this autumn he won the Forward Prize for Best Collection for Notes on the Sonnets (Penned in the Margins). Set at an awkward house party, it is a response to Shakespeare’s sonnets. The judges praised his book for capturing the “uncomfortable elements of human interaction and the changing nature of love”.

But Kennard isn’t here to talk about poetry, or not really, or about academia, or not really. He’s here to discuss his second novel, The Answer to Everything (Fourth Estate), which charts how an emotional affair blooms via WhatsApp between two neighbours. It’s a painfully honest, moving look at the realities of being a parent, and where that loss of a sense of self can lead. It’s also really, really funny.

Emily, the mother of two young children, is struggling. She and her husband Steven—dependable but monosyllabic—have moved to a new estate, but she feels lost and unfulfilled with life, with parenthood, with her marriage. “Why did she feel, permanently, as though she were waiting for a train that wasn’t arriving at a station that no longer operated?” When the couple meet their new neighbours Elliott and Alathea, also parents of young boys, she and Elliott begin texting late into the night.

“Emily was never sure why she laughed so much in correspondence with Elliott, or at least typographically represented it. It seemed to have less to do with whether something was especially funny and more mutual validation,” writes Kennard insightfully. Soon their relationship has crossed over into something Emily is hiding from Steven, even though she is sure that having an affair is the sort of “sad, dull, disastrous thing which adults did, and even in her thirties with a husband and two children of her own, she still felt sort of like a child”.

Text appeal

The novel started, says Kennard, with the idea of these hundreds of obsessive text messages going back and forth. “There are levels of intimacy that we have rapid access to now that we didn’t before, and there is something interesting and dangerous in that. When a text message cost 12p to send, they were generally quite terse,” he says. “I was investigating where the line was. Obviously with Emily and Elliott, it very quickly becomes more than just a quick check-in, they develop this sort of emotional dependence with each other; they manage to have a secret co-dependent relationship alongside their real-world relationships. I felt as though that might be a common enough experience to resonate.”

Emily and Elliott’s back and forths are sharply amusing, as each does their best to impress the other. Kennard is fascinated by that disconnect between the version of ourselves we can project via social media or text, and the reality. “A real relationship is when you have enough respect for that person to prioritise the real them over your version of them—you’re not constantly being like, ‘This is not how my idealised version would behave’,” he says. “But you can always collude with somebody in any type of emotional affair, you can collude with them to create an idealised version of each other—a kind of fictional us, a fictional self and a fictional them as well—that you can then just cause a world of pain to. It’s real and unreal at the same time, and you can sort of get away with it to yourself, even if you would like to think of yourself as someone with standards and morals.”

Kennard is also very good on the simultaneous boredom and adoration that comes with being a parent to very young children; at one point, Emily sees a film of herself playing in the park with her son Arthur. While she remembers the moment as a fun, playful one, in reality she is shown to be “vacant, staring, not at her son but into the middle distance”. Kennard has children of his own, who are currently nine and seven, but they were much younger while he was writing the novel back in 2017.

“It’s the sheer physical exhaustion of it: a two-year-old needs picking up constantly, comforting constantly, you do not have a moment to finish a thought, let alone a verbal sentence with anyone, let alone your partner. It’s having to do what feels like the hardest thing you have ever had to do, on very little sleep, on very little inner resources,” he says. “My feeling was that this can put you in a quite vulnerable position where you’re like, ‘I need an escape’. That’s part of what triggers things between Emily and Elliott: there’s a vulnerability there that maybe wouldn’t be there at different times in their lives.”

The poet’s path

Kennard has written both fiction and poetry since he was young, studying English Literature at Exeter University before taking an MA in creative writing, and then working for four years at Somerset County Council in the finance department, which left him with “so much mental energy to put into writing”.

He then embarked on a PhD, on the prose poem, and in 2007, when he was 26, became the youngest poet ever to be shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best Collection for The Harbour Beyond the Movie (Salt). He has been teaching at Birmingham since 2008, writing “three failed novels” before The Transition, his début, was published in 2017. He currently has a draft book of poems he is working on, about Jonah, the follow-up to his collection Cain (Penned in the Margins), and is in the first stages of drafting his third novel.

Poetry, he says, is easier for him to write than fiction. He wrote his Forward Prize-winning collection in spare half-hours because “it was so process-driven, it was like, read a sonnet, react to it in some way, get something down about that, and then eventually go back and revise it”.

He adds: “Maybe it’s the kind of poetry I write, which is really self-conscious and quite narrative-driven, but quite dreamlike as well. I find that I can just tap into that, I can just start writing and I really quickly know whether I’ve got something or I haven’t. If it’s not going anywhere, if it’s falling flat, I just scrap it, it’s 20 minutes and it’s fine. But sometimes you catch something. And it’s kind of a pleasure anyway, you’re just playing with these ideas, you’re playing with language. It feels like... I’m not a talented musician, but it feels like a kind of musical improvisation, just the sheer joy of playing an instrument.”

With fiction, though, he says he has “to set myself a word-count target, and the painful thing about that is that sometimes you have 30,000 words and you realise it’s not going to go anywhere. There’s not enough to it. The writing isn’t beautiful enough to sustain the lack of plot. It feels like a lot more time and effort to let go of. I’m never upset about scrapping a poem, I’m always upset about scrapping fiction.”