You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

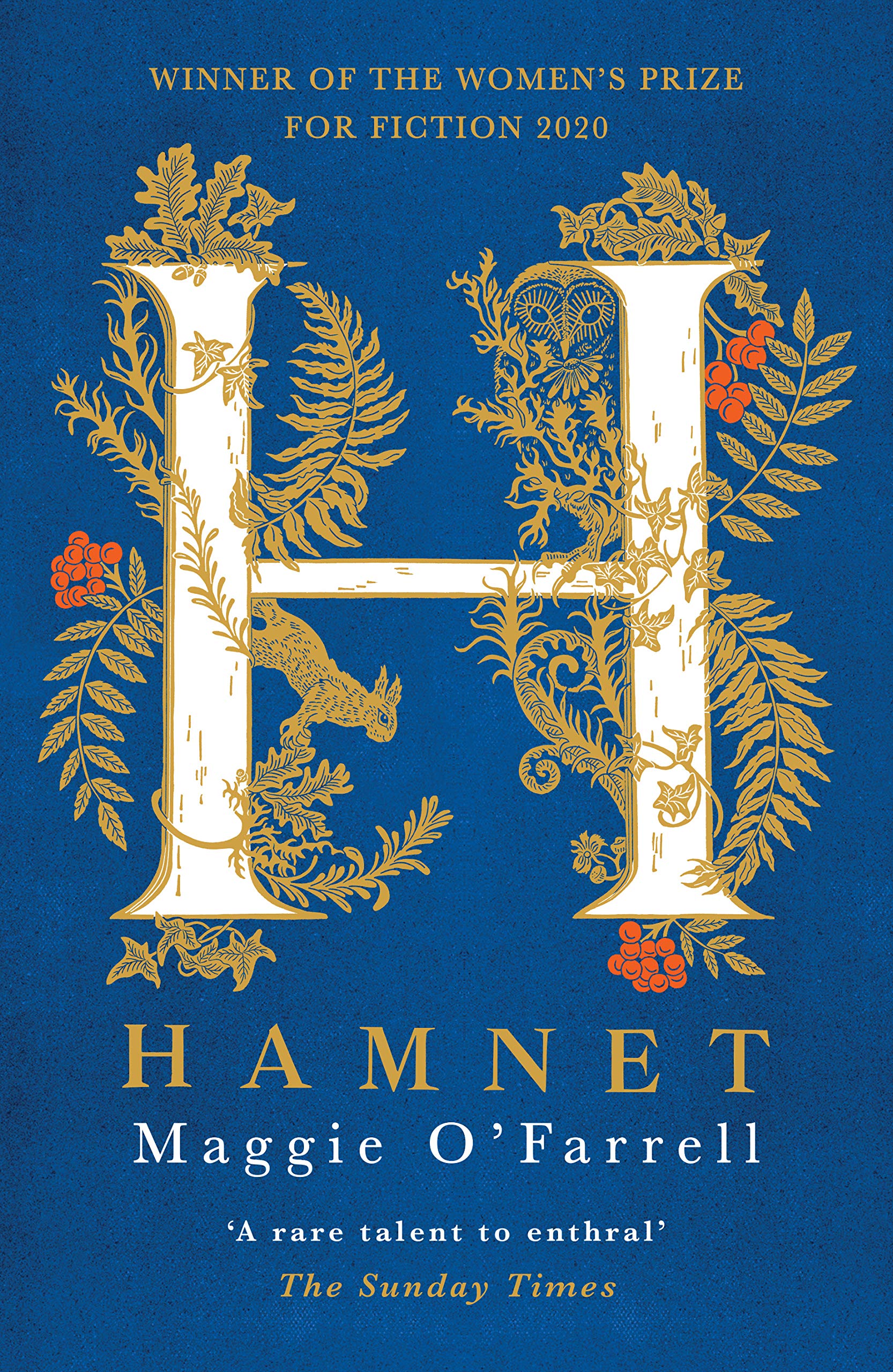

Maggie O'Farrell talks about uncovering lost stories and voices in her new novel, Hamnet

After seven novels and a hit memoir, Maggie O’Farrell turns her hand to historical fiction with the tale of Shakespeare’s lost young son, who inspired his most famous work

In order to trace the roots of Maggie O’Farrell’s eagerly awaited new novel, one has to travel back 30 years or so, to a chilly Scottish classroom where an English teacher named Mr Henderson was preparing to teach “Hamlet”. He told his class that Shakespeare had a son called Hamnet, who died several years before the play was written. Now, sitting in a warm café in north London, O’Farrell remembers her younger self being immediately struck by this, wondering what it meant for a father to name a tragic hero after his dead son.

A few years later, reading English at Cambridge, she discovered that Shakespeare’s only son barely merited a paragraph in even the chunkiest biographies, and this information would always be followed by a comment about the high child mortality rates of the time. “The unspoken implication was that it didn’t really matter because it happened such a lot. Even before I had my own kids [she has three], I thought, ‘How can that be true? He was 11!’” she exclaims, disbelievingly. “It would have had an enormous impact.”

These people, this household, who were so important to one of the best writers who has ever lived, have been all but forgotten

Hamnet (Tinder Press, March) is O’Farrell’s tender response to this neglect. In beautiful, lyrical prose, it tells the story of Shakespeare’s lost son, Hamnet, and imagines the tragic events of August 1596. “It’s a story about a boy who has been consigned to a literary footnote. I wanted to give him a voice, and his mother and his sisters too,” she says. Hamnet had a twin, Judith, and an elder sister, Susanna. “These people, this household, who were so important to one of the best writers who has ever lived, have been all but forgotten.”

The novel is also the untold story of Agnes, Shakespeare’s wife and Hamnet’s mother—more commonly known as Anne Hathaway. O’Farrell takes issue with the depiction of Anne/Agnes as an older woman who lured Shakespeare into marriage (she was 26, he was 18) and from whom he couldn’t wait to get away to London. Her Agnes is a free-spirited, intuitive woman from a wealthy family, a herbalist and the novel moves back in time to show how Shakespeare, when he was still an impoverished tutor with a disgraced glove-maker father, fell deeply in love with her. “I wanted her to be this character who had her own brand of intelligence and perspicuity about people. She saw something in him because she could see into people, and that’s why she chose him.”

Close to home

O’Farrell has wanted to write Hamnet’s story for years, she says, so I wonder why now? Her answer is surprising: “I’m not a very superstitious person, but I was very superstitious writing about an 11-year-old son dying, while my own son was still not yet that age,” she says. “I knew that I would be thinking about my son. That’s just what happens when you are creating the character of a boy; you are thinking about how they behave, what their interests are, how they talk, how they come into a room. And I knew that I would have to put myself inside the skin of a woman who watches her son die and lays him out for burial. And I couldn’t do it!” she says. “I couldn’t do it, until [my son] was safely past that age.”

Hamnet’s death, and his lifeless body being laid out and prepared for burial by his mother, is one of the most powerfully moving depictions of grief and loss I have ever read. “I had to write it outside the house,” O’Farrell tells me. “It was almost as though I didn’t want to summon that image inside the house where my children lived.” She wrote those heartbreaking scenes in a dilapidated greenhouse in the garden of her home in Edinburgh, in short bursts, interspersed with walks around the garden.

Hamnet is O’Farrell’s first historical novel, but her eighth novel overall. For a novelist who has made her name with contemporary fiction, I wonder if she found writing historical fiction based on real events constraining at all? Not at all, she says. Her previous book was the memoir I Am, I Am, I Am: 17 Brushes with Death, and with Hamnet “it was such an enormous relief to go back to making things up!” Writing a novel set in the 16th century was, she notes, “a really interesting discipline... It felt like going right back to the beginning [as a writer] and starting out all over again. I had to forget everything I had learned—you can’t just reach for your usual metaphors.” She poured over an enormous Oxford English Dictionary with a magnifying glass, checking for first usages and jettisoning any anachronistic words, no matter how perfect the image. “It made me work incredibly hard, and really pare it all back to the very bare bones, which is a very exciting way to write; fine-tuning the language and keeping a sharp weather eye on everything you are doing.”

I wanted to know what it felt like to dig a patch of ground, to plant these plants from seed, to watch over them and water them

The novel is rich with detail about 16th-century domestic life, which is due to the fact that whenever O’Farrell reached an impasse with the writing, she would go off and do some practical research. Besides learning how to fly a kestrel and mudlarking in the Thames, she planted her own Elizabethan medicinal herb garden, despite not being much of a gardener, and went on a course to learn how to turn the herbs into medicines. “I wanted to understand the labour involved in these tasks, because that’s the thing I kept coming up against, particularly about women’s lives at the time, that we have no concept of the labour involved. I wanted to know what it felt like to dig a patch of ground, to plant these plants from seed, to watch over them and water them.” She also wanted to “get really close to the sensation of what it would be like for your child to have a deadly illness, and all you have are these [herbs]. How would that feel?”

Two decades in

Publication of Hamnet in March 2020 will mark 20 years to the month of O’Farrell’s début, After You’d Gone, which achieved immediate critical and commercial acclaim. Eight novels and one memoir later, with numerous Costa Novel Award shortlistings—and a win for The Hand That First Held Mine in 2010—and a devoted readership, O’Farrell visibly squirms when I ask about her impressive career. But to stay at the top of the bestseller lists for 20 years is no mean feat. She is that rarest of writers; a genuine literary/commercial crossover. “You have to write the book that you can’t not write,” is all she has to say about her success. “You mustn’t try and second-guess what people might want, or what your editor might want.”

Unusually, O’Farrell has been with the same editor, Mary-Anne Harrington, since the very beginning and says “my books wouldn’t be anywhere near what they are without her help and insight”. Writing a book, says O’Farrell, is a bit like ascending a mountain: “You get completely lost, in a bog or a forest, you have no idea where the summit is. And your editor is the person flying down to you, with a light and a snack and a map, saying, ‘You know what, the summit is over there!’”