You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Malachi McIntosh on morals and fairytales in his short story collection

First hone your craft via the short story, says Malachi McIntosh, former editor of literary magazine Wasafari. Then you can attempt the novel.

What is it about short stories that appeal to you?

I think I’m a bit of an accidental short story writer. Most of my education took place in the US and my desire to write really crystallised while I was over there doing a BA. At the time I studied, the model I absorbed for a writing career was that you hone your craft learning the art of the short story and then you, effectively, graduate to writing novels. During my BA I wrote a lot of short stories—all in pursuit of some kind of mastery, and then a magic graduation that never quite came about.

What I like about short stories is that they offer infinite possibilities for play. Experimentation in a novel can get exhausting, but the brevity of the short form means you can attempt some zany things and not overstay your welcome in your readers’ heads. That’s kind of how they function for me: as playgrounds and laboratories to try things out, test ideas, discover answers I didn’t expect, and explore.

What resonated with and surprised you while compiling your stories into the collection?

So many things. This project began with a recognition that I had years’ worth of stories on my hard drive that I had never really tried hard to do anything with. I would send a story to two or three magazines, get the nice rejection letter, and just give up on it. After two decades of doing that I had a bulging file on my computer called “Oddities” and, in a general pandemic-inspired life-reassessment, I went into it and started rooting around and thought that some of the work had some hope.

The Emma Press had put out one of its regular calls for pitches and, knowing Emma Dai’an Wright, its editor-in-chief, through my time [as editorial director] at [literary magazine] Wasafiri, I asked if she would be interested in looking at a pitch. I threw together what I thought were the best stories on my computer, expecting another nice rejection and she said, basically, surprisingly, “I like these but not these, what else have you got?” It was the first editorial conversation like that I’d ever had—hopeful. I then sent some alternatives and some more alternatives and ideas and, after maybe two months, we were working on a collection.

One of the best suggestions she made from an early conversation, that quelled a lot of anxiety, was that the stories didn’t have to be thematically unified, that they only needed to harmonise with each other in the way songs might on a good mixtape. So I guess the biggest surprise was how well thinking of it like a collection of music worked for me. And then, in the final reshuffling of material, how the stories all, unintended by me, were at some level about storytelling—about the kinds of stories we tell to ourselves about ourselves and the stories we tell about other people to position and make sense of ourselves. It was a completely accidental theme. It’s a totally logical preoccupation of someone writing their first collection, but it really surprised me. I’m still not fully sure what to make of it.

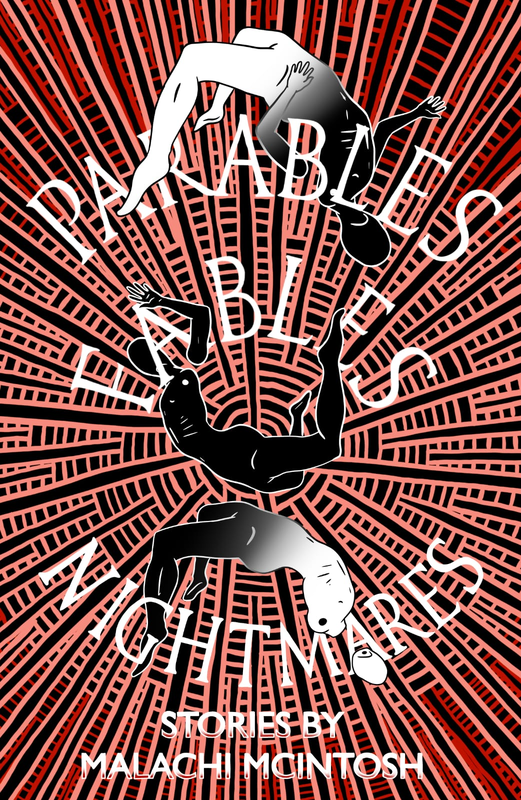

The title for your amazing collection is Parables, Fables, Nightmares. Parables and fables are genres that suggest a moral imperative; what morals are the tales imparting on the reader?

An important final stage of writing fiction for me is always to ask, “So what am I saying here? What is this thing revealing to me about what I think about the world?” I’m not sure if everyone who writes asks that or if it’s an emanation from my day job [McIntosh is a lecturer of English at the University of Cambridge]. I’ve also been frustrated by what I feel is a kind of overarching nihilism in a wide range of contemporary narrative. I find the sum total of much written in the last few years is something along the lines of, “Everyone is compromised. Everything is morally suspect. Shrug.” Which is something I just can’t follow.

We have spoken of mutual adoration of John Gardner, who has a little cameo in the book, and my favourite work of his is On Moral Fiction, which basically argues that all good fiction has a moral imperative and, further, ought to. I’m not sure if I agree with the last part, but I do feel that the books that have moved me most in life have had some animating interest in the good—what it might be to live well, even if only by portraying its absence.

Elements from fairytales permeate a number of the stories, for example we have döppelgangers in “Mirrors” and a ghastly arrival in “Limbs”. What is about fairytales that resonate with you?

This is one of those things that I really wouldn’t have seen myself. I would go back again to being moved by stories with a clear moral imperative, I think. And perhaps stories that aren’t too hung up on realism.

My favourite story is “The Emperor’s New Clothes”. It’s a perfect parable of the self-perception of those in power and how it’s enabled by those who pretend they don’t see what they see in order to advance their own interests. Once you have read it and understood it, it functions as a lens through which all sorts of actions in the world beyond the story can be read. I suppose I aspire to writing with that force; writing in a way that could change the way a reader sees the world.

You can’t move for multiverses these days, so if you were to send a story to yourself when you were editor at Wasafiri, what advice would you give your younger self about your writing?

Lord, I think I would say, “Just keep writing”. As I get older I wish I could reach back to that younger self and say, ‘It’ll be alright. It worked out alright”, about so many things. A really concrete piece of advice is to stop editing. To know when to stop. There’s a Toni Morrison Paris Review interview where she talks about worrying a piece of writing to death, and I did that all the time—revised and revised and revised the magic out of something, the way you can erase and redraw a pencil sketch into just wrinkled paper.

We are arguably in a boom of interest in Black British writers, but the thing about booms is they tend to bust. What do you think publishers and writers can do to make sure the boom is sustained?

Stop presenting Black writers as primarily valuable for their anthropological interest, for what they can potentially teach readers about the perspective of the Other. Read our work and present us as artists, like our peers, hurled into the lives we’re in and using our writing to make sense of where we are and the world around us. It’s true that no small percentage of Black writers through history have written works that focus on the experience of being minoritised, but through that they have tried to illuminate another aspect of what it’s like to live in their era. We write about being. We think about living. Value us for that.