You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Maria Ressa shares how we can all speak truth to her power in her new book

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

Nobel Peace Prize-winner Maria Ressa has long spoken truth to power—and in her new book, she shares how others can too in order to build a better world

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

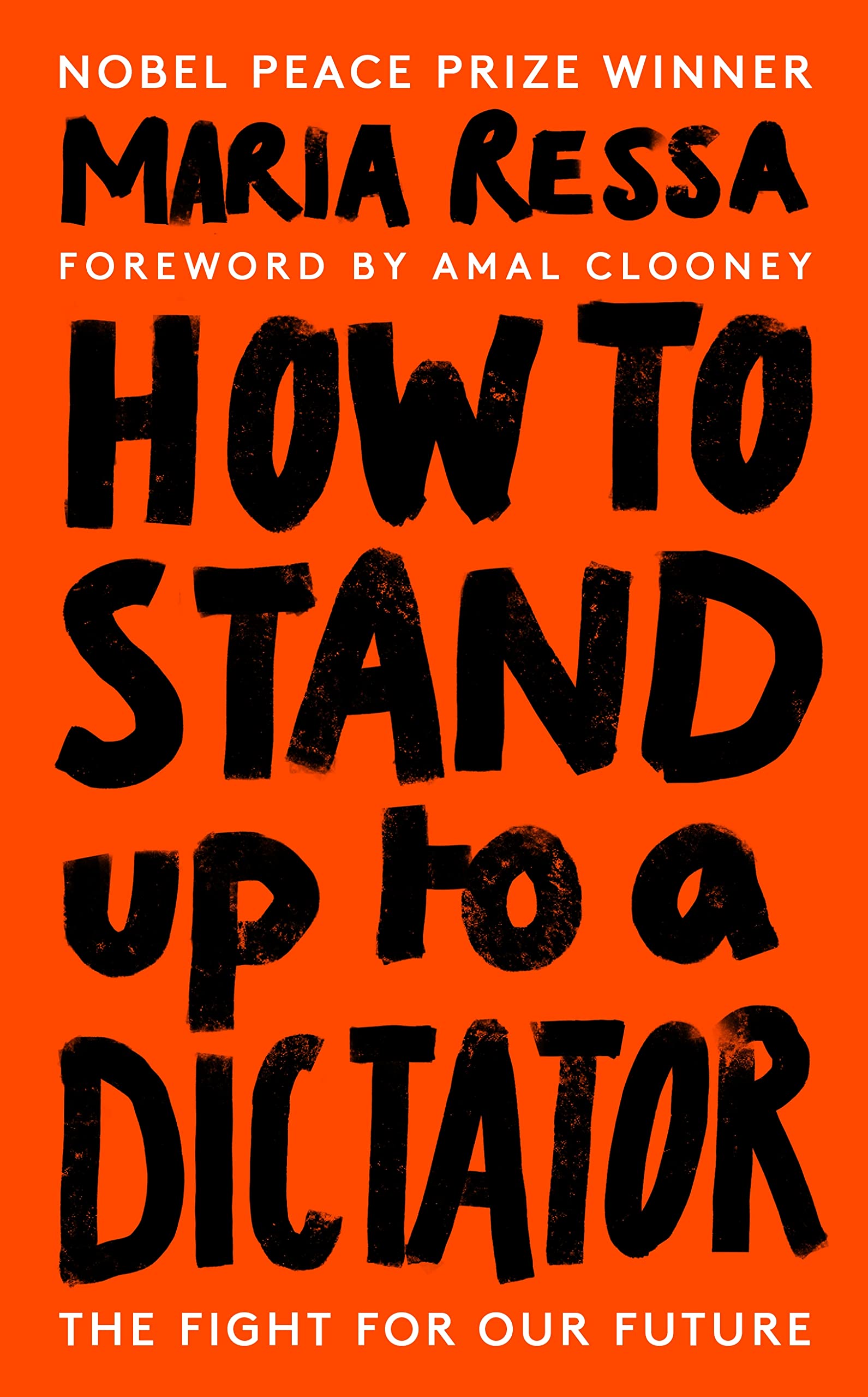

"I may go to jail. For the rest of my life—or, as my lawyer tells me—for more than 100 years. On charges that should never even have made it to court. The breakdown of the rule of law is global, but it has become, for me, personal. In less than two years, the Philippine government has filed 10 arrest warrants against me.” So writes Filipino-American journalist Maria Ressa, winner of the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize, in the opening chapter of her remarkable book, How to Stand Up to a Dictator: The Fight for Our Future (W H Allen).

Part memoir, part manifesto, it charts Ressa’s career in journalism as an Asian migrant to the US who subsequently returned to her homeland. It reflects her conviction that “an invisible atom bomb has exploded online”, killing our freedoms in the process.

An ebullient presence on my screen, Ressa speaks to The Bookseller via Zoom from New York City, where she has flown from her home in the Philippines to give a speech at the Chautauqua Institution; the same venue where Salman Rushdie was attacked on 12th August. It’s a prospect that is unlikely to daunt Ressa, a veteran of speaking truth to power who has won many awards for her work, but has also endured numerous virulent attacks designed to destroy her professional reputation. In bestowing the Peace Prize on Ressa alongside fellow journalist Dmitry Muratov from Russia, the Nobel Committee called them representatives of all journalists who stand up for such freedoms “in a world in which democracy and freedom of the press face increasingly adverse conditions”. Human rights barrister Amal Clooney, who has advised Ressa and has written the foreword to the book, says of her: “Maria Ressa is five foot two inches, but she stands taller than most in her pursuit of the truth.”

I think in this age, we have forgotten what journalism is, and it’s been cheapened to the point where it’s meaningless

I begin by asking Ressa about her own freedom to travel: she is due to speak at the Edinburgh Festival and at an Ebury showcase in London at the start of September.

Currently on bail, she recently lost her appeal against a conviction for cyber libel in a Philippines court and now faces a lengthy prison term, pending a mooted appeal to the Supreme Court. “I have to get court approval each time I want to travel. This time it was granted. But it’s been random. In 2020, the government prevented me travelling five or so times, including a trip to the US when my mother was having an operation. I never know whether I can travel until the day before my flight is supposed to leave. I’ve learned to be OK with it but it’s part of the reason why I’m so adamant that we protect these freedoms—because it’s so easy to lose them.” While some of the cases against Ressa have been dropped, it remains to be seen which will be pursued by the new Philippines administration of President Bongbong Marcos (son of Ferdinand and Imelda), who was elected in May. “Holding the line”, as Ressa calls it, of investigative journalism has cost her media company Rappler “tremendously, both in terms of time and money”, with the prospect of bankruptcy a constant threat, alongside that of incarceration.

Crossing continents

Born in the Philippines in 1963, Ressa migrated to the US at the age of 10. After graduating from Princeton University, she returned to her native country on a Fulbright scholarship and stayed. There she built a distinguished career in broadcast journalism, reporting from across Southeast Asia for CNN, and later joined major network ABS-CBN as the director and producer of Probe, the first and longest-running investigative news magazine in the Philippines.

In 2012, she launched Rappler, a digital media company for investigative journalism, along with her three female co-founders—or “manangs” as she calls them, a Filipino word which translates as “older sisters”. In recent years, Rappler has focused critical attention on the regime of former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte, including his controversial anti-drugs campaign, which has resulted in a death toll so high that Rappler dubbed it “a war waged against the country’s own population”.

It is this reporting that has landed Ressa with multiple arrest warrants. She has also long taken Facebook to task for allowing its platform to be used “to spread fake news, harass opponents and manipulate public discourse”, because she believes that as the world’s largest distributor of news, it presents “one of the gravest threats to democracies around the world”.

Over time you realise that if you don’t stand up to a bully, it dictates everything

At the heart of How to Stand Up to a Dictator is a call for a return to rigorous investigative journalism, “operating under a strong standards and ethics manual”. She tells me: “I think in this age, we have forgotten what journalism is, and it’s been cheapened to the point where it’s meaningless. If I hear someone call a journalist an influencer, I get crazy. Because journalism requires so much discipline and courage to do well.” Right across Southeast Asia and beyond, from the Philippines to Indonesia and Singapore, she has witnessed many transitions of leadership, and this experience has instilled a belief that the “quality of a democracy is determined by the quality of its journalism”.

Ressa also makes much in the book of having strong personal values, “so you’re very clear what lines you can’t cross”. The memoir part of the book is instructive in showing how Ressa’s own values were forged as “the shortest, only brown kid” in her public elementary school, where she experienced bullying. “Over time you realise that if you don’t stand up to a bully, it dictates everything. And what social media has done is put us right back in grade school.

It’s like a popularity contest where a bully can gain great control over the landscape and where popularity can turn into mob rule.” In her Nobel acceptance lecture, Ressa called for a collaborative “person-to-person defence of our democracies”, and in her book she aims to show how we go from the “personal to the political, and from individual values to a pyramid for collective action”.

I think so many people—the majority of us, the moderates in the middle—tend to keep quiet

In answer to my question about how this might translate into individual actions, she says: “It’s not just that you pledge not to be corrupt and not to violate the principles of free speech yourself, but that you also pledge to call out corruption and the suppression of free speech in your area of influence. I think so many people—the majority of us, the moderates in the middle—tend to keep quiet.” Global initiatives with similar aims are also crucial, she says—and indeed, a few days before our interview, Ressa was appointed to the UN’s inaugural leadership committee on internet governance.

She argues there could not be more at stake right now, with more than 30 national elections due to take place across the world in the next couple of years, including in Brazil, Turkey, India, Indonesia and the US. “If nothing substantive is done, by the end of 2024 we will we have elected enough illiberal leaders to tilt the geopolitical power balance”, she says.

Extract

“The struggle of man against power,” wrote Milan Kundera, “is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” We have been laughing at memes and forgetting our history. Even our biology, our brains and hearts, have been systematically and insidiously attacked by the technology that delivers our news and prioritizes the distribution of lies over facts—by design.

I have lived through several cycles of history, chronicling the wild swings of the pendulum that would eventually stabilize and find a new equilibrium. When journalists were the gatekeepers to our public information ecosystem, those swings took decades. Once technology took over and abdicated responsibility for our emotional safety, history could be changed in months. That’s how easy it became to shift our memory through our emotions.

When that happened, it destroyed the old checks and balances on power and transformed our world.

It’s a terrifying prospect. But although Ressa is a woman with every reason not to smile, she does so frequently. Throughout her distinguished career, she says she has experienced the worst of human nature, but also the best of it, telling me of a man she met as a reporter whose house in the Philippines was constantly destroyed by typhoons, but who always shared what little food he had. “I’m always on the side of hope. Because while I’m old enough to know that evil exists, to do good, you have to believe there is also good in the world. And that’s where I am.”