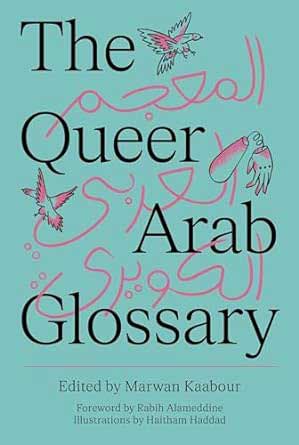

Marwan Kaabour chats about his book, The Queer Arab Glossary

The Queer Arab Glossary, compiled by Lebanon-born writer and graphic designer Marwan Kaabour, explores the Arabic queer experience.

"Slang fills in the gaps where conventional language fails", according to Marwan Kaabour, the editor and compiler behind The Queer Arab Glossary — the first published collection of Arabic LGBTQ+ slang and idiom, which is published by Saqi in early June. It is rare for most people to have any true insight into the Arabic queer experience—be they within that intersection or on the outside of it — and this gloriously confident book will be an eye-opening, often unashamedly sexual, revelation and an education to most.”

But despite being frequently rooted in the day-to-day trade of sexual expression, the book acts as a canny entry point into something a lot deeper. "It might seem niche in its subject matter," Kaabour reckons, "but in the course of learning about the language, you’re going to learn about colonialism, you’re going to learn about the history of the region, too."

Kaabour was born in Lebanon, Beirut, in 1987, into — as he sees it — "the extreme privilege of a loving and supportive family" His mother was a painter, his father a protest musician. Both never felt his queerness was "an issue of serious contention". Having graduated from university into a career as a graphic designer, a feeling he was settling down too soon drove him to start a new chapter of his life in London.

In the course of learning about the language, you’re going to learn about colonialism, you’re going to learn about the history of the region, too

Kaabour eventually became ensconced at Barnbrook — the multifaceted design studio headed by Jonathan Barnbrook. In his time there, he worked on projects for Banksy’s “Dismaland” and designed the much-praised The Rihanna Book, a Time Magazine Best Photo Book of 2019. Kaabour’s first major project however was "Takweer", an Instagram page that has since become a thriving platform and community for all things Arabic and queer — be they memes, slogans, pop-culture snippets or deep dives into queer history. It is never not thought-provoking, visually arresting or playful — that last quality being frequently lost in the issues-centred coverage of either Arabic lives or queer worlds. "We live, we party, we cruise and we fuck," states Kaabour. "We make connections and relationships; these things exist in all our lives. It would be a shame just to focus on the onslaught of documentaries and films about how tormented we are because we are multifaceted, complex, contradictory human beings. It’s important that we show the full range of stories around us."

An average "Takweer" post might feature clips of a spectacularly camp Egyptian pop performance from the 1980s, or a knowing nod and wink at the perhaps-inadvertent campness of some founding tenets of Islamic tradition, such as the ‘winged, ornate, androgynous and flamboyant creature’ of The Buraq: a bejewelled horse-like creature that once carried the prophet Muhammad.”

Named knowingly to evoke both the word "queer" and the Arabic word "takwir" (meaning ‘to create in the form of a sphere’), "Takweer" is an almost entirely unique cultural repository, a rare link between two concepts that many outside the Middle East are rarely prompted to compute: that there is such a thing as a thriving culture around being gay, lesbian, bi, trans and LGBTQ+ in the Arabic and Muslim worlds.

"We sometimes appear in pop culture and in history as though we are a Western import," reckons Kaabour. "But it’s a fallacy. I try to debunk those myths by showing people what we do. It’s easy to just look to things like the Stonewall Riots and “RuPaul’s Drag Race” and other iconic Western queer landmarks, but it is a lot nearer and dearer to our heart to find those reference points in our own environment. With The Queer Arab Glossary, I wanted to show how our language is rooted within the Arabic language."

Kaabour began to dwell on the plurality of words, phrases and slang idioms that Takweer’s community had exposed him to, many rooted around sexual characteristics, tropes and desires. "Because I’m from Lebanon, my dialect is Levantine," states Kaabour. "I am familiar with the dialects of neighboring countries, but not slang from further away. When I interacted with people from other regions, they would use words I didn’t know to describe things like gay or queer or lesbian. So I thought it would be interesting to create a linguistic mapping of queerness in the region." Very quickly this led to Kaabour owning a heaving spreadsheet of sexual expressions on his computer, detailing words such as "Abū Frūkh" (a word in the Gulf dialect to describe an older gay man who is attracted to twinks) or "Shawwāya", which in Maghrebi literally means a "grill rack" but denotes a versatile gay man who flips over during sex, like meat on a grill.

Around 300 similar words are all lovingly distilled into The Queer Arab Glossary, and are bolstered by eight supporting essays that elucidate on linguistics, history and queerness under titles such as "An Effeminate Moroccan" or "Are You a Pan-Arab Nationalist or Just a Man Who Sleeps With Men?"

The evolution of language

Further highlights of the book are the illustrations by Palestinian artist Haitham Haddad, which work to pick out certain words from the glossary and, according to Kaabour, "personify them to create these almost mythological queer Arab deities. Maybe they were words that have a negative connotation, but here we inject them with joy and pride and see them exist in an almost fantastical world". Thus we see the word "shaykha"—a word used by lesbians as a term of respect for an older lesbian of high regard—illustrated by a majestic woman sitting confidently on a throne, a sleeping cat at her feet.

Feeling it was "vital for this book to be published by an Arab publisher, to retain complete authorship over the subject," Kaabour came to regard Saqi—the independent academic and trade publisher with a focus on the Middle East and North Africa—as the best fit for the project.

It’s uncertain just yet whether the book will be released in the region it focuses on. "In the past year specifically, there has been a spike in violent, aggressive, homophobic attacks in the region," says Kaabour, which makes independent bookshops nervous about displaying it. "I think it has to do with the fact that queer people are slowly but surely becoming more public and visible." Interestingly, the word "queer" is used increasingly across the Arabic world (just as its use has spiked in the UK in recent years), which perhaps informs Kaabour’s choice of "queer" in the title. He feels it was a natural choice for the times. "Although there has been a lot of discourse lately around how lots of us have adopted it versus specific labels like ’gay’, in the moment that the book was published, this was the closest term I could get to being the right one. Language will endlessly be fluid and changing. And all of these crazy fights we have about language will be irrelevant in a few years."

While language may never be set in stone, it’s a rare blessing for all of us that The Queer Arab Glossary manages to capture a slang consciousness that otherwise might have slipped by.