You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

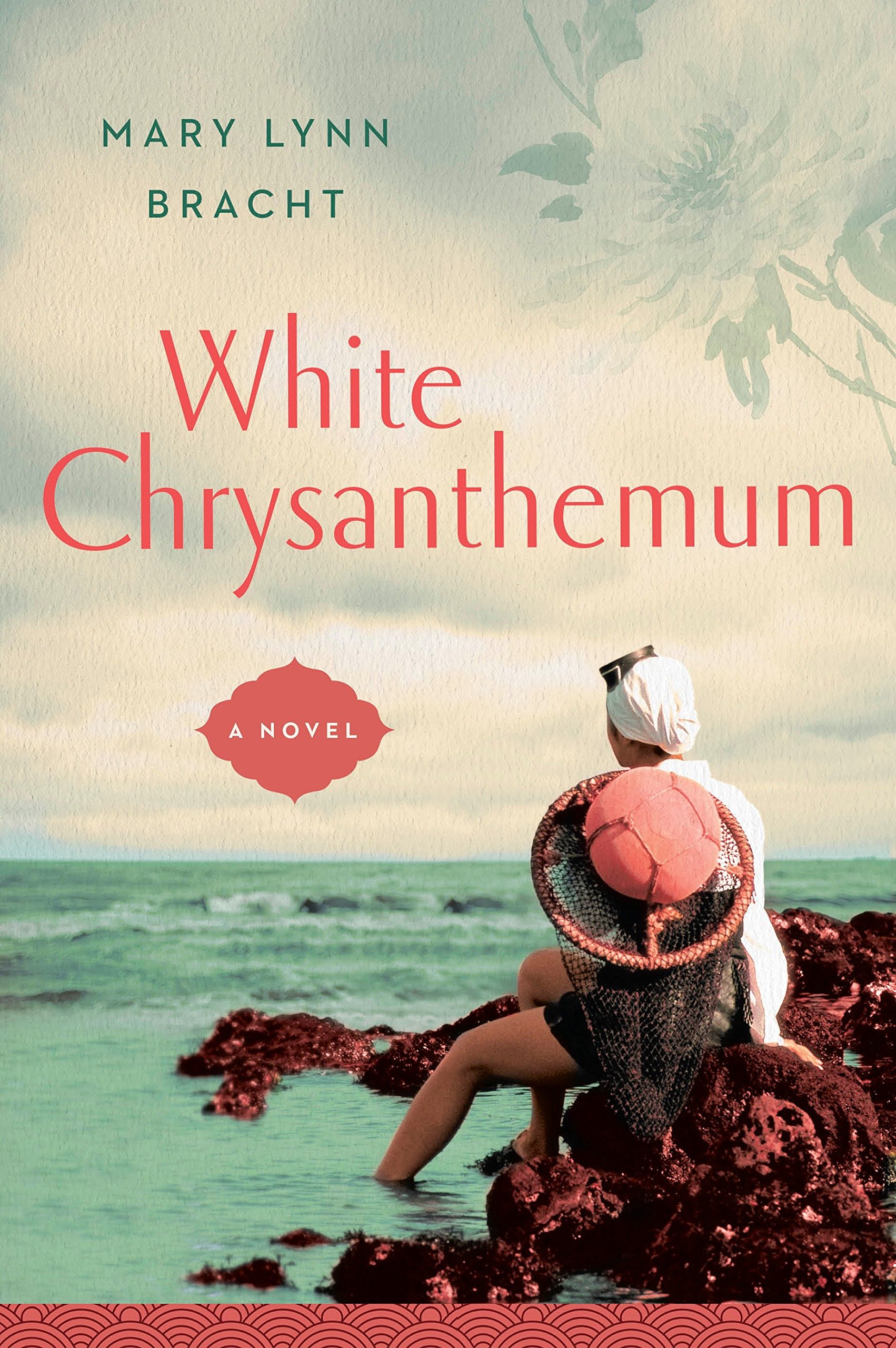

Mary Lynn Bracht breaks the silence on the plight of Korea's 'comfort women' in her historical debut

A literary historical début, the redemptive tale of two sisters torn apart by the Second World War, breaks the long-held silence on the plight of Korea’s “comfort women”

Women’s stories resonate with me. Powerful women. I feel like my mother and her friends are survivors of their own histories,” Mary Lynn Bracht says, as she explains the inspiration behind her moving début, White Chrysanthemum (Chatto, January), which has seen her literary career come into bloom. Thrusting a forgotten corner of history into the light, and already eliciting comparisons with Memoirs of a Geisha and The Kite Runner, Bracht’s novel was pre-empted in the US and the UK for six-figure sums within hours of final edits at last year’s London Book Fair.

The novel introduces 16-year-old Hana who, while protecting her little sister Emi, is forcibly taken away by a Japanese soldier to become a “comfort woman” for the Japanese army. Reinforcing the book’s feminist thread, the women are from a fiercely proud lineage of haenyeo (female divers who harvest marine life from the ocean floor) on Japanese-occupied Jeju Island, Korea, where, unusually for the broader patriarchal society, they are the breadwinners. Despite the atrocities each is forced to suffer in the other’s absence during the war—as the narrative moves between Hana’s struggle to survive in the 1940s, and Emi’s struggle with survivor’s guilt as an elderly woman—their sense of self and sisterhood endures.

What does it take to endure that kind of slavery and want to live? Who was that person? I knew it was the haenyeo

“They had to keep going, they had no choice. I can’t imagine . . . I can’t, and I can, all at the same time,” says Bracht. “For me, I had to think, who are the women who survived? Because out of 200,000 [registered “comfort women”], by the 1990s, only 250 were still alive. That’s a massive amount of dead women. What does it take to endure that kind of slavery and want to live? Who was that person? I knew it was the haenyeo.”

But while Hana comes to represent the historical pain of all “comfort women” (or “grandmothers”, as they were also known) coerced into military brothels, it is Emi, who avoids that fate, to whom Bracht feels she is closest. “She survives the war and continues to live in Korea, and is an example of the women who just got through it, sort of like my mother and her family,” she says. “When nothing happens to you except life, that can be just as hard.”

Before resolving to become a writer, Bracht wanted to be a soldier like her father, who, when traveling in Korea in the 1970s as part of the US military, met Bracht’s mother. They would later move the family to suburban Texas, where Bracht grew up in an expat community of Korean women, many of whom left behind difficult pasts but, like her mother, are survivors and storytellers. “I grew up always listening to these stories from my mother’s homeland, so I was always interested in what was out there, what was beyond Texas. Anytime I thought, ‘What do I want to write about? What inspires me?’, it was always my mother and things about her life and her history,” she says.

It wasn’t until Bracht had swapped drills and combat boots for an anthropology degree, however, that she discovered the subject of her first novel, in time opening the door for her to pursue her passion. Initially discouraged from the writer’s life, Bracht was in training to become a fighter pilot when a chance module took her in a different direction. “I’m from a very small town, nobody became a writer!” she laughs. “I wanted to write stories, I always had stories. But I decided not to, so I went to college to become a fighter pilot. In my freshman year I was on the airforce scholarship and somewhere in there I took an anthropology class. And I thought, ‘I don’t want to kill people, I want to study people.’

But it was this terrible thing in history that just shocked me

“When I heard about the ‘comfort women’, I was at a point when I was already researching Korean history. Probably over 12 years passed before I decided I would put this somewhere. I wrote a short story, which became my masters thesis, which became my novel. So it was a very long journey. But it was this terrible thing in history that just shocked me. I read a lot of the stories and they were very difficult reading—very tearful, a lot of pauses. It’s like a re-living. I came to it from a historical point of view because it’s a story that’s not really told.”

Breaking the silence

“When I asked my mother, ‘Did you know about comfort women?’, her response was shocking. She said, ‘Oh yeah, everyone knows about them’. And that was it,” recalls Bracht. “I think part of it [being accepted] is that terrible things happened to women in Korea throughout history anyway. It struck me that this feeling is still keeping the ‘grandmothers’ searching for justice and resolution to what happened to them today. It was this feeling of, ‘Yeah it happened, it’s not that big a deal’. To me, imagine what if you were that woman? You’re about to die, and all your life people have been calling you a whore. Argh, that just killed me.”

Anything that has to do with sex is, ‘hush-hush, let’s not talk about it, we don’t want to talk about it

Although tens of thousands of women were tricked or kidnapped into sexual servitude for the Japanese military during the war—testimonies suggest that some were forced to have sex with up to 50 men a day—the issue was buried for half a century. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the mood of the country changed and, in 1991, the first “comfort woman” came forward. By this time very few were left, begging the question, how many died in those years of silence? And how was it left unacknowledged for so long, given the scale of the tragedy? “The mistreatment when they came forward was just terrible. People said they were money-grabbing whores,” says Bracht. “At the time, chastity was life or death. And to have this happen to you, there is no talking about it. If you can escape talking about it, pretend it never happened, you can possibly have a life.”

Still seeking justice

Not only were the women forbidden to speak of the abuse they suffered: in December 2015, as part of a ¥1bn deal between the Japanese and Korean governments intended to settle the matter, a monument erected in their honour was ordered to be removed from outside the Japanese embassy in Seoul. “When things happen to women like this, the government is trying to sweep it under the rug. It doesn’t want to remember. It doesn’t want the statue and the memorial to remember the victimhood and survival of these women. It would rather they just silently go away,” says Bracht. “Anything that has to do with sex is, ‘hush-hush, let’s not talk about it, we don’t want to talk about it, we can’t put it out there right away’. No, what’s going to happen to the women, and the children? You can’t just leave them out.”

Extract

Hana knows that protecting her sister means keeping her away from Japanese soldiers. Her mother has drilled the lesson into her: never let them see you! And most of all, do not let yourself be caught alone with one! Her mother’s words of warning are filled with an ominous fear, and at sixteen Hana feels lucky this has never happened. But that changes on a hot summer day.

It is late in the afternoon, long after the other divers have gone to the market, when Hana first sees Corporal Morimoto. Her mother wanted to fill an extra net for a friend who was ill and couldn’t dive that day. Her mother is always the first to offer help. Hana comes up for air and looks to the shore. Her sister is squatting on the sand, shading her eyes to look toward Hana and their mother. At nine years of age, her sister is now old enough to stay on the shore alone but still too young to swim in the deeper waters with Hana and her mother. She is small for her age and not yet a strong swimmer.

Hana has just found a large conch and is ready to shout at her sister to express her joy, when she notices a man heading toward the beach. Treading water so that she can lift herself higher to see him more clearly, Hana realizes the man is a Japanese soldier. Her stomach knots into a sudden cramp. Why is he here? They never come this far from the villages. She scans the beach within the cove to see if there are more, but he’s the only one. He is heading straight for her sister.

When asked if she’d consider the book a feminist novel, she pauses. “I think it’s a human novel. It’s about women, it’s about what happens to women in war, and these particular women in sexual slavery. But I hope everyone reads it, actually. When I was doing research I’d go to bookshops [to read about the war] and not only were the patrons all male, the books are all male too—it’s all about fighting and that kind of sacrifice. This is the other side. I think it’s a hole in our history; I would like to see it filled a bit more.”