You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

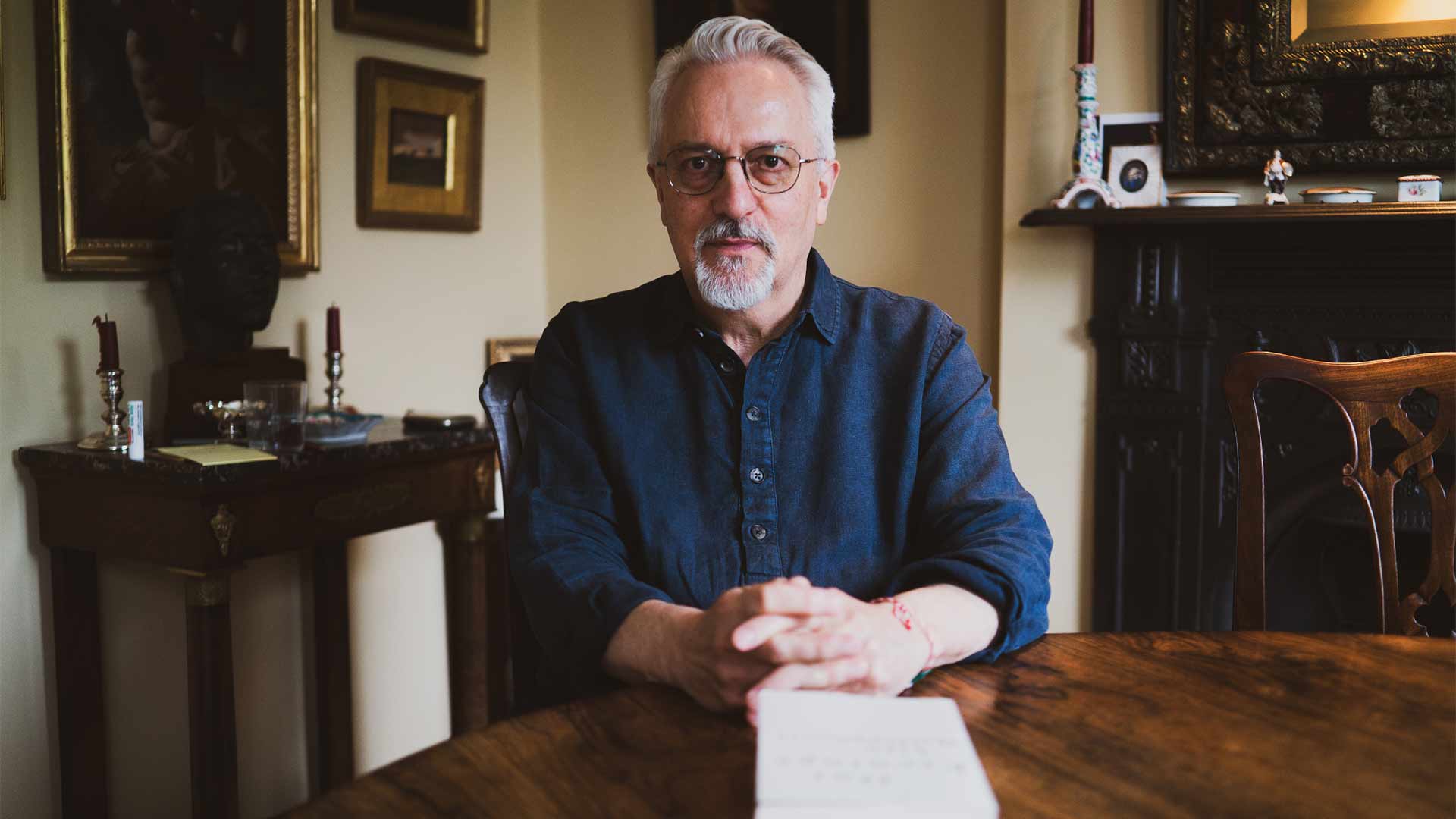

Matt Parker | 'I view a Sudoku as a tiny insight into what it's like to be a professional mathematician'

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

Ask mathematician Matt Parker what his favourite number is, and you won’t get some namby-pamby random answer like seven or 11 (even if 11 is the only palindromic prime number with an even number of digits). “At the moment, it’s 2,025”. “And why is that?” I enquire, acutely aware of my (scraped) Grade C in O-Level Maths.

“Because it’s a square number: 2,025 is 45 squared; 45x45=2,025. And because in the year 2025, I will turn 45. Very few people ever get to be the exact square root of a year: 1980 is one of the rare years where it works.”

It appears that Parker—whose début, Things to Make and Do in the Fourth Dimension (Particular Books, October) is set to do for maths what Keri Smith did for creativity, according to Penguin—was destined to be a mathematician from the year of his birth in Perth, Western Australia. Encouraged by his accountant father he started doing sums at the age of three or four. “He kind of tricked me into it, selling it as a reward and fun. Brainwashing is very effective. When I got to school, I already thought maths was brilliant. And even though I then realised that not everyone else was as excited about it, by then it was too late. The damage had been done”.

After a double major in Maths and Physics at the University of Western Australia, Parker trained to be a maths teacher, and moved to the UK in 2005. He was soon striving to make maths fun for the most reluctant of students. “If you say: ‘Alright, forget the fact that you’ve going to need this for a mortgage one day, but learn this bit of maths and you can do a card trick to annoy your friends and family,’ then you’ve got them.”

After a while, Parker decided that he wanted to try and enthuse a wider range of people about maths, and hit upon the idea of combining his passion with comedy. “I’d done bits of comedy when I was at university, and a lot of teachers make very good stand-ups—[they are] used to talking to an audience while monitoring what everyone’s up to and gauging the mood. So you come with all these transferable skills.” After a course in stand-up, he was soon gigging regularly on the UK comedy circuit, developing routines which were increasingly maths-themed.

A piece of the pie

These days, when Parker “mentally pie-charts up his life”, a third of his work is with schools and a third is stand-up comedy, with the final slice devoted to broadcasting and writing, although his first love remains teaching. Since 2010, he has been Public Engagement in Maths Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London; has appeared on BBC Radio 4’s “The Infinite Monkey Cage”; and has performed his stand-up maths routine in front of thousands of people around the world—including at the Hammersmith Apollo, where he did live maths in front of 3,500 people. In 2012, he and the Think Maths team (of entertainer/educators, which he founded) made a fully functioning computer using 10,000 dominoes. YouTube contains plenty more evidence of his maths-proselytising stunts, from the 49 Card Trick to a stand-up routine about barcodes.

The idea for the book arose naturally from all the fun activities Parker had developed, but structuring it so that the chapters would both stand alone and have a logical progression was an enormous challenge. “My girlfriend was writing a book at the same time, so we rented a cottage. I cleared all the furniture out of one room and filled it with bits of cardboard for the chapters, and my stack of ideas on Post-it notes all colour-coded to link together.”

Things to Make and Do in the Fourth Dimension is full of puzzles and hands-on activities to engage even the most arithmophobic, by making maths feel less about maths and more about life. Why slice pizza straight across the middle when there’s a more interesting way of doing it, one which shares out the central topping more fairly? While eating it, you can amaze your friends by fitting a 2p coin through a 5p-sized hole. Or by counting to a million on your fingertips, or making an emergency pentagon, or getting 12 oranges into “kissing” position. Some of the concepts in the book will boggle most brains not used to considering such knotty matters as hyperbolic geometry (“the Meissner tetrahedron, you know you want one”), prime numbers (“the A-list celebrities of maths”) and, err, knot theory. But there is still plenty to entertain readers whose grey matter can’t quite stretch to doing the actual maths.

Doing maths for its own sake is a raison d’etre for Parker, who often converts photographs into Excel spreadsheets for fun. “That’s the dirty secret of mathematics; that the vast majority of it happens solely because mathematicians thought it would be fun or interesting to look into it. Lots of people do Sudoku puzzles, because they’re kind of fun, and satisfying when you solve them. I view a Sudoku as a tiny insight into what it’s like to be a professional mathematician.”

“Where does the fourth dimension of the title come in?” I ask, slightly dreading the answer in the knowledge that the chapter on tiling mere 3D shapes has already blown a fuse in my brain. “Well, everyone is kind of aware of the fourth dimension, but no one knows what it is. Physicists try and own it by saying the fourth dimension is time, which it obviously isn’t. In the book I show people how to build a 4D cube out of straws, or at least a 3D shadow of what the 4D cube would look like. Because, despite our brains having evolved to deal with 3D space (using mathematical logic and a hands-on activity), we can still explore objects in a higher dimension than we can directly access.”

My multi-dimensional interview with Parker is unlike any I have ever done. I get to play with his Borromean Rings, for one thing. I come away with my name written out in binary (another of Parker’s many party tricks); a gift bag of three wooden, non-circular shapes that roll (demonstrating why 50ps and 20ps work in vending machines); and a new method of tying my shoelaces.

“You must be a hoot at dinner parties,” I say. And sure enough, while we have been talking, the Stand-Up Mathematician has been eyeing up my tallish, thinnish glass tumbler of Penguin HQ water. “Look at that glass. Which is bigger, the height or the circumference?”. I reply: “The height”, without a shadow of a doubt crossing my mind. “Well it’s got to be the circumference by a long shot. Because if I circle my thumb and index finger around it, I can’t touch them together. But if I measure the height with the same fingers, I’ve got a huge overshoot. Apart from the tallest, most extreme champagne flutes, it’s the same for all glasses.”

Do try this at home.

Metadata

Publication 30.10.14

Formats HB/EB

ISBN 9781846147647/9781846147654

Rights US (Farrar, Strauss, Giroux), Israel, Japan, Russia, Canada

Editor Helen Conford, Penguin

Agent Will Francis, Janklow & Nesbit

CV

1980 Born in Perth, Western Australia

1999-2002 Double major in Maths and Physics at the University of Western Australia

2003-2004 Qualifies as a teacher, teaches in Australia

2005-2009 Works as a maths teacher in the UK

2010-present Public Engagement in Mathematics Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London