You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Megan Nolan in discussion about her latest novel exploring family, morality and addiction

The themes of family and addiction lie at the heart of Megan Nolan‘s new novel.

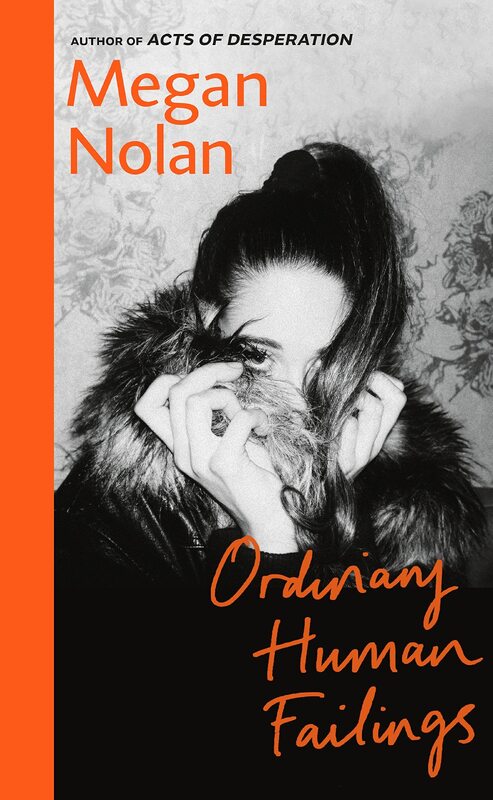

It was a single line in a book about a serial killer that planted the seed for Megan Nolan’s eagerly awaited second novel, Ordinary Human Failings. Over Zoom from a friend’s place in Brooklyn where she is currently cat-sitting—she grew up in Waterford, Ireland, and now lives in London—Nolan explains that, around eight years ago, she read Gordon Burn’s book about Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, Somebody’s Husband, Somebody’s Son.

Sutcliffe’s family were approached by a tabloid journalist after his arrest but before he stood trial and were offered the chance to stay in a hotel at the newspaper’s expense. “[The family] would have pocket money and limitless booze, basically, so it was to have a source on tap and keep them sequestered from other newspapers. [The book] didn’t go into any detail about what that was like, but I was very struck by the idea of what that hotel would have been like, what a pressure cooker it would have been.”

Ordinary Human Failings opens in 1990. Tom Hargreaves is a young ambitious tabloid reporter who, through pure chance, is the first to hear about a toddler who has gone missing on a London council estate. As he walks around the housing estate after dark in pursuit of the story, listening to the idle chatter and speculation of other residents, he learns that the missing three-year-old, Mia, was last seen playing with a slightly older child, Lucy.

One of the real overarching aims with the novel was that I wanted to counter the idea that there might be one reason for someone’s bad—I don’t know that I’d want to call it bad—behaviour

Thrillingly—from Tom’s point of view—it turns out that Lucy is the daughter of an Irish immigrant family who kept themselves to themselves and were regarded with suspicion by their neighbours. When Mia is found dead by the bins early the following morning, with bruising round her neck, Tom’s “missing person” story takes a potentially sensational new twist. The police take Lucy in for questioning and Tom befriends her family, spiriting them away to a hotel in the hope that they will spill their stories.

Heart of the matter

At the centre of the reclusive Irish family is Carmel, who was a teenager when she gave birth to Lucy. Carmel’s older brother Ritchie is a part of the household too, with their taciturn father, John. Tom sits with them in the bar until the small hours, waiting for the free booze to loosen their tongues.

Tom is convinced that the family are concealing a big secret, something he can turn into front-page news to bolster the story he has talked to his editor about. Nolan writes: “It could be interesting, could it not? he asked. Say this is true to whatever degree, say the kid of Family Bad Apples has maybe killed the kid of Family Do-Gooder. Even if it doesn’t bear out in the end, or doesn’t come to trial, or get a conviction, it could be interesting in the meantime. 90s Britain, the Battle of the Council Estate; feckless foreign wanderers with a whiff of abuse and chaos turn on the Deserving Poor.”

You will have to read the novel to find out if Tom unearths what he is looking for, but Nolan observes: “There’s a fairly simplistic way of thinking about trauma sometimes, where there’s a big explanation for everything and it’s this one event. One of the real overarching aims with the novel was that I wanted to counter the idea that there might be one reason for someone’s bad—I don’t know that I’d want to call it bad—behaviour, but that there’s some easy explanation for people’s unkindnesses and their violence and their lack of ability to live in a steady, normal way. That was why I wanted to go back into the past, not just Carmel’s past but her father’s.”

I have such empathy and interest in addiction, but it is very frustrating to be around somebody who won’t help themselves, so it was a challenge

Ordinary Human Failings then moves back in time, to Waterford in the late 1970s, to tell the story of why the family were compelled to leave Ireland and settle in London. All the family members are convincingly realised: dreamy Carmel (whose plans to leave small-town Ireland for brighter lights are cut short), her mother Rose and father John, but it is Ritchie, a chronic alcoholic, who is perhaps the most heart-breakingly and sensitively drawn. “It’s a terrible plague in every community, but where I’m from it’s pretty visible; it’s a small, tight-knit community and you really see the effects of addiction.” Nolan says that she knows people who suffer with the disease: “I have such empathy and interest in addiction, but it is very frustrating to be around somebody who won’t help themselves, so it was a challenge, and one I really wanted to do with Richie, to actually break down what he was thinking while he was doing these apparently insane things.”

Nolan is at pains to make clear that the act of violence in the novel is not based directly on any real-life crime committed by a child, “but I am fairly passionate about the dehumanisation that happens [in the aftermath]. People are so repulsed by the idea of a child doing something so dreadful and so violent that they almost can’t extend any empathy… that was one of the main things I was thinking about before I began writing.”

I was terrified to be honest with you, in a way that I wasn’t with the first one because the first one felt very like ‘this is my story to tell’,

Certain sections of the media are ready, especially with families from a working-class background, to “almost write people off as born evil, or born ready to do these things”. Nolan describes herself as being “from a notoriously bad estate in Ireland so I had [an] interest in the ‘bad’ areas, the ‘bad’ neighbours and estates”.

The author’s outstanding début novel, Acts of Desperation, marked her out as a fearless writer with its intimate, visceral account of a toxic relationship told from the inside. Whereas she drew on her own life for her début—she has said that the narrator’s feelings, impulses and emotions were based on her own experiences, but the events they were attached to in the novel were fictional—Ordinary Human Failings unfolds on a bigger canvas, with multiple characters and told in the close third person and marks a confident evolution in her writing.

In contrast to Acts of Desperation, which she worked on closely with her agent from the beginning, Nolan didn’t show Ordinary Human Failings to anyone until she had finished the first draft: “I was terrified to be honest with you, in a way that I wasn’t with the first one because the first one felt very like ‘this is my story to tell’, my one shot to tell an important thing about life as I see it and I didn’t see myself as [becoming] a novelist per se, as having an ongoing career.”

She wanted to try her hand at a “family saga” this time. “Not to be self-deprecating about the first one but do a proper novel, you know,” she says laughing. “The family is the heart of it for me, and I hope that those characters are what connect with people rather than the ostensible ‘mystery’. The family is what I think about when I think about the novel, and what I feel most proud of.”