You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

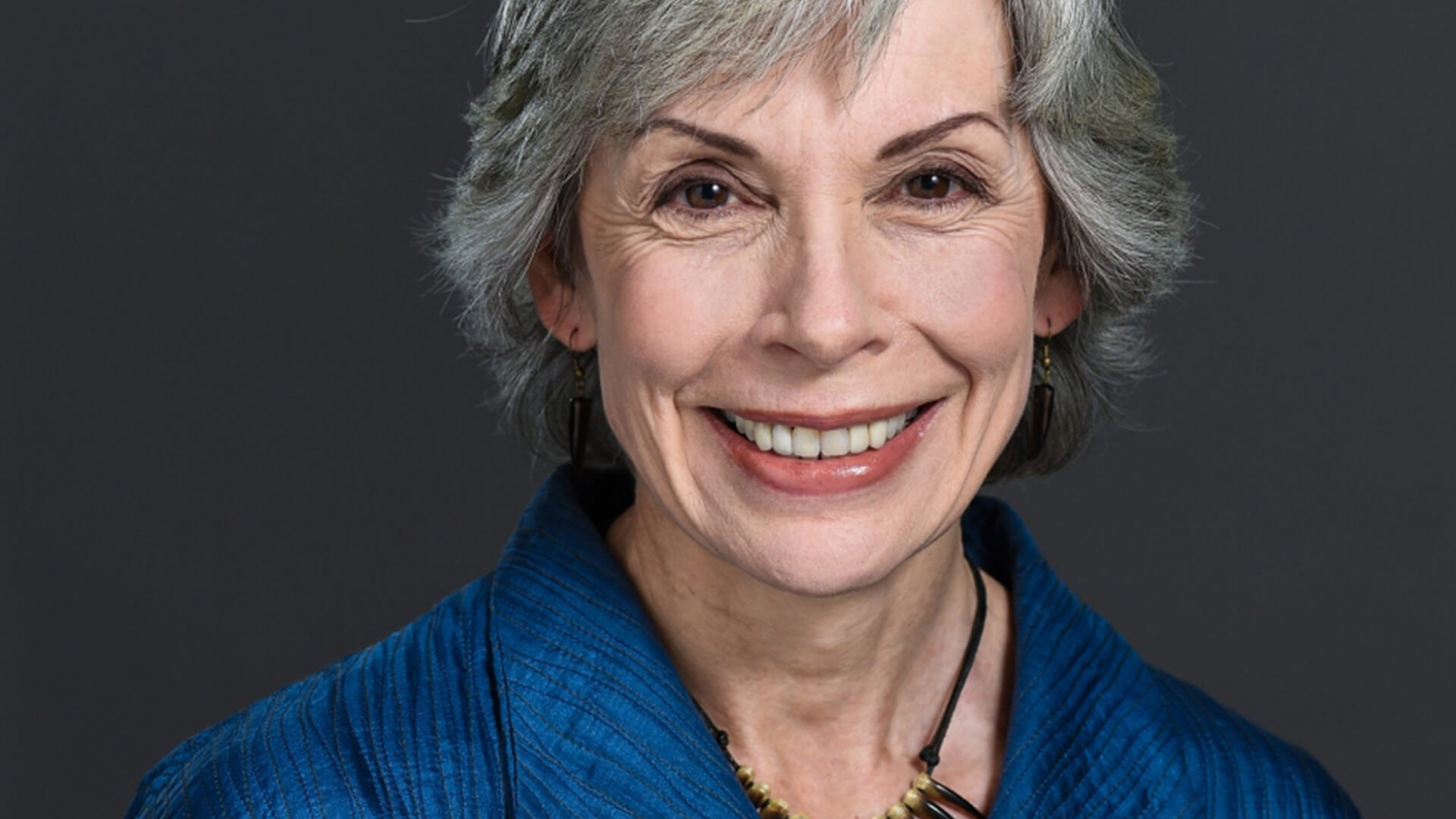

Michelle Paver, the Stone Age, harsh existences and the beauty of nature

Michelle Paver’s latest novel is a return to the world of her bestselling Wolf Brother tales

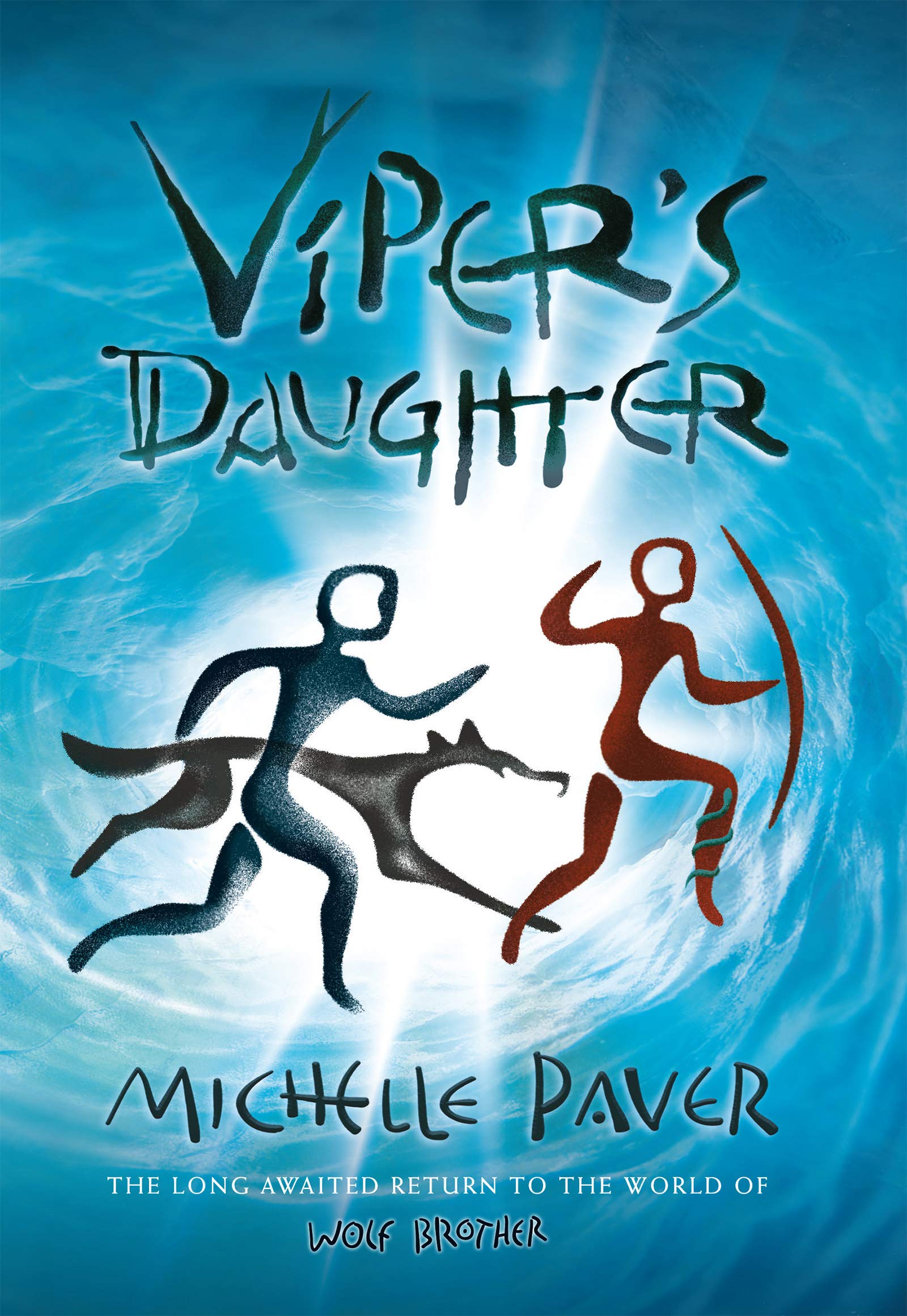

Michelle Paver never intended to write a sequel to her bestselling Wolf Brother series. “I’ve always said—and I meant it—that was it. It was six books, it had shape to it, I’d given Torak and Renn a good send off and I meant it, totally.” But in April, 11 years after the sixth book, Ghost Hunter, comes Viper’s Daughter, a brand new adventure set in that Stone Age world, published in hardback by Head of Zeus.

I meet Michelle in early December, the buzz of festive central London a world away from the ancient forests of her stories. Wolf Brother was published in 2004 to huge acclaim: the media was hungry for the next Harry Potter, and Paver recalls being on the “News at Ten” on launch day. The book introduced Stone Age boy Torak and his animal companion Wolf, and the thrilling tales of clans, demons and survival, which have gone on to sell more than three million copies in 37 territories.

I had to take the view that I was introducing a nine-year-old to these books and this world

Paver has written many other bestselling books for both children and adults—the Bronze Age Gods and Warriors series; gothic thrillers Dark Matter and Wakenhyrst—but I get the sense that none have touched her in quite the same way. “Normally when you write a book, I find the characters leave you,” she explains, “like they’re your grown-up children and they’ve gone off. But genuinely, Torak and Renn and Wolf did stay with me. I thought about them a lot.”

Paver speaks with such affection that I am only surprised it has taken her this long to return to them. Enthusiasm from fans was another factor: she continues to receive letters from readers young and old. The most common question is always: Please, will you do a sequel? “That has an effect,” she laughs. But, she stresses, the concept of a new book hinged on “a really good idea”. Then in 2015, Paver was in north Norway, tramping through a snowy forest, when she saw the Aurora Borealis pointing north and felt the essence of her story begin to stir.

Picking up

Viper’s Daughter takes place just two summers after the events of Ghost Hunter. It was, Paver tells me, “very important to grow it organically” from the earlier books. How is the relationship between Torak and Renn developing? What is the fallout from everything they have been through? For existing fans, it has to seem like the next instalment but at the same time “it needs to be completely standalone and a completely new introduction” for first-time readers.

This “tricky but fascinating” challenge of bridging old and new readers was, Paver admits, the toughest task in writing the book. “I had to take the view that I was introducing a nine-year-old to these books and this world. They’ve never been in the Stone Age before; they don’t have a clue who Torak, Renn and Wolf are. How do I make them feel immersed and care about this strange, rich new world?” Research and brainstorming followed—“always”, she laughs, “more fun than the actual writing”. Along with a re-read of the existing books, Paver created a “bible” of continuity notes, chronicling every detail of Torak’s world. Very quickly she realised the story would be three books, due in part to the narrative arc of her “stonkingly good” villain. In the interest of minimising flying she planned two research trips to serve the trilogy: one to Alaska and the Haida Gwaii islands off British Columbia, the other “a wild trip” up the Bering Strait to remote Wrangel Island, the last home of the woolly mammoth, which plays a key part in the book.

They have this grim existence, but the sense of beauty and observation of animals is fantastic

Paver’s journeys permeate her work with rich detail, bringing not only the landscape to life but the human existence too. She encountered the Chukchi people, whose tough childrearing customs inspired the book’s Narwhal clan. She shows me a tiny delicate seal, carved from antler, which lives on her writing desk. “They have this grim existence, but the sense of beauty and observation of animals is fantastic.” Her own extraordinary wildlife experiences become Torak’s: polar bear tracks on every single beach; a wolverine frozen mid-snarl; a mammoth tusk sticking out of a dry river-bed.

Changing times

Fifteen years ago childhood looked very different, without phones, Alexa or social media. Does Paver find her readers much changed since the publication of Wolf Brother? She had fears of a generation lost to screens, but finds that for many modern children her books offer a refuge from modern life. She sees “a yearning for a world without screens.

Yes, it’s rough and Torak and Renn go through some difficult times, but it’s this amazing world where there’s no climate change, lots of animals, no pollution. It doesn’t matter what you look like. What matters is you don’t make any noise when you’re hunting.” The physical freedom and sense of wilderness taps into children’s passion about the environment and living sustainably. Loneliness is another common feature of children’s letters to her, and the character of Wolf and the “total loyalty” of his bond with Torak speaks deeply to those readers.

Paver writes first in longhand, then on a 23-year-old computer backing up on floppy discs. She describes herself as a meticulous self-editor. “What I call my first draft has already been through multiple drafts.” Viper’s Daughter and, before it, Wakenhyrst, have seen her re-united with Fiona Kennedy, her editor and publisher of the original series at Orion Children’s Books. She is clearly thrilled to be working with Kennedy once more and tells me it would have been “unthinkable” to do another Wolf Brother book without her.

"Right from the start, she absolutely got what I was trying to do, it’s always been such a wonderful editorial experience.”

Paver has enjoyed success writing for both children and adults; how differently, I ask, does she approach the two disciplines? The children’s books, she explains, tend to have shorter chapters with cliffhanger endings to keep the pages turning, but she works to one very specific guiding principle. “I very much want to make sure that any child reader doesn’t feel worse about the world when they’ve read my books.”

Although there are some very dark moments, “I visualise a golden thread of loyalty and friendship, and love personified in the friendship of Wolf and Torak,” she says. “Hope is so important. Everything you do can make

a difference.”