You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Natasha Brown follows her much-feted debut with a pin-sharp tale of class, wealth and manipulation

In a nutshell, I read books for a living. I interview authors for The Bookseller's weekly Author Profile slot and write the monthly New T...more

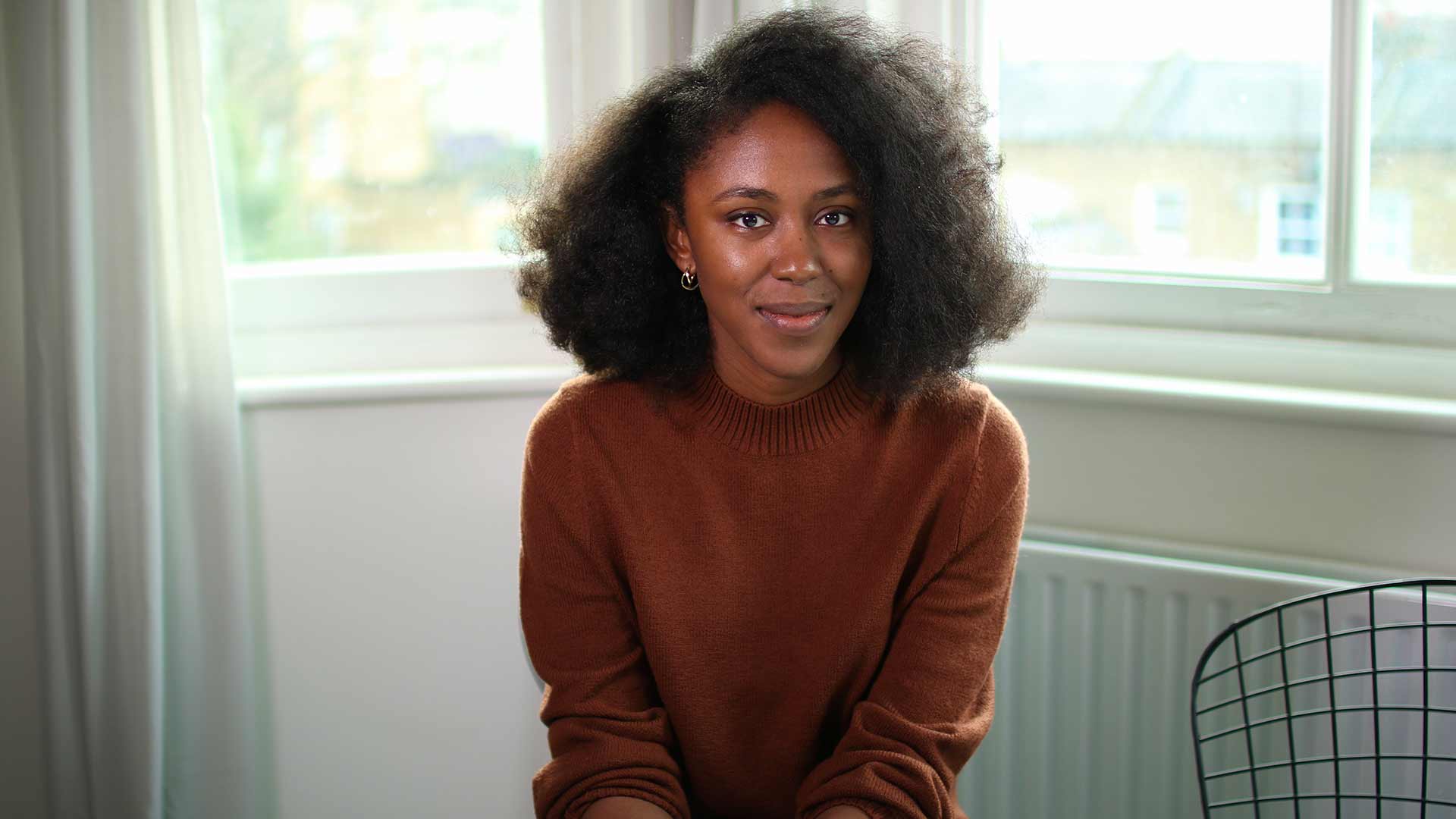

Now selected as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists, Natasha Brown returns with a dazzling second novel.

In a nutshell, I read books for a living. I interview authors for The Bookseller's weekly Author Profile slot and write the monthly New T...more

Natasha Brown’s first novel, Assembly, was one of the most-fêted literary debuts of recent years. Shortlisted for, among others, the Goldsmiths Prize, the Folio Prize and the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction, it also saw her named as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists in 2023. Her second novel, Universality, more than delivers on the promise of her first. It is terrific; a pin-sharp, savagely funny tale of class, wealth and manipulation.“I’ve always been really interested in this question of language,” says Brown, who is a warm and softly spoken interviewee, when we meet in a cosy bar in south-east London. Whereas Assembly was concerned with how the unnamed narrator, a Black British woman, “interacts with the words around her, I thought it would be interesting to take a look at people who use words – people who are very good at using words – for profit, to change people’s minds, to create narratives.”

Universality opens with a (fictional) piece of long-form journalism titled A Fool’s Gold, taken from Alazon magazine. It begins with an attack, the weapon a gold bar that was subsequently stolen, at an illegal rave held at a banker’s country escape during lockdown. As a news story it was quickly forgotten. But, the Alazon journalist writes: “The missing gold bar is a connecting node – between an amoral banker, an iconoclastic columnist and a radical anarchist movement.”

The article tackles the mystery of the attacker’s identity and the whereabouts of the stolen gold bar. The plucky young journalist interviews the legal owner of both the Yorkshire farm, where the rave took place, and the gold bar. Richard Spencer is a banker who, the journalist writes, had enjoyed “all the excessive fruits of late capitalism… multiple homes, farming land, investments and cars; he had household staff; a pretty wife, plus a much younger girlfriend”. Other players scrutinised in the piece include the squatters (or “self-sustaining community” depending on who you ask) who had taken over the farm: Indiya, a Home Counties hippy art student turned eco-activist and self-described “hardcore Marxist” and the (amusingly named) fellow radical, Pegasus. Also making an appearance in the piece, which goes viral, is another journalist, Miriam Leonard, aka Lenny, a popular right-wing newspaper columnist and author of No Mo’ Woke.

This opening section of the book was inspired by Tom Wolfe’s New Journalism movement, Brown tells me: “Taking novelistic techniques and applying them to non-fiction writing… the idea that journalists can transcribe the subject’s thoughts and feelings and motivations for doing things”, a sort of blurring of fact and fiction. Brown had noticed how “this sort of narrative has really heated up on the internet”, citing Cat Person, the short story by Kristen Roupenian, which appeared in the New Yorker and went viral online, that some readers mistook for journalism.

Becoming a full-time novelist would really make me worry about taking risks in the way that I write

Brown is also “a fan of linked short story collections or novels-in-flash and the way they play around, with earlier sections reverberating later on. I thought it would be really fun to do that in a way that you don’t quite see how they fit together to begin with.” Indeed, the subsequent sections of Universality – each named for the location where they take place: Edmonton, Weybridge and a prestigious literary festival in Cartmel – reveal more about the characters in A Fool’s Gold and their hidden motivations, including the author of the piece, freelancer Hannah. No spoilers here, but by the end of the novel, an economical 128pp, Brown has ingeniously turned what you think you know on its head.

She is an admirer of Herman Koch (The Dinner, Summer House with Swimming Pool): “He’s really good at creating these nasty characters and bringing you inside their minds, slowly revealing not just their nastiness, but how their nastiness is supported by social niceties.”

In Universality she wanted to “embrace some of the nastiness”. Richard Spencer, the filthy rich banker, was the first character to take shape. He appears in Assembly as “a very minor character”, says Brown, but she had already fleshed him out: “With Assembly I wrote from the other characters’ perspective before I wrote the narrator’s perspective, so I had a novel’s worth of background material.” He was followed by Lenny, “his worst nightmare”, who is a monstrously compelling character. Does Lenny believe her own right-wing rhetoric, or does she do it for clicks and giggles, I wonder? Brown says it was fun to “really lean into the ambiguity” here. She researched by reading a lot of columnists of a certain stripe: “It took a lot of research to get her voice and pull it off consistently, particularly because she breaks out of voice quite often or adopts different ones. It was very tricky, but I felt she was very satisfying to get right.”

Brown skewers her characters to the page and has a gift for capturing social situations with precise attention to detail. The Edmonton section involves Hannah hosting an awkward dinner party for three friends from whom she has drifted apart since university, the ever-widening gap between her freelance income and their big salaries proving almost unbridgeable until her sudden, unexpected success with the piece: “I think it’s that social interactions don’t come very naturally to me. You know, I’m a maths geek. It took work and effort to figure out how to feel effortless or appear effortless in social situations. I think when it doesn’t come easy, you think more carefully, perhaps, about actually how are people doing it.”

Brown read mathematics at Cambridge University and didn’t even consider English literature: “I don’t know; it just seemed like not even a possibility, I guess.” It meant dodging the long reading lists: “I got to read what I wanted to read.” And in any case, pure maths is very creative she says: “You can prove one result multiple ways, but some proofs just feel more elegant and more beautiful than other proofs.” She went straight into a finance job in the City but is now taking the career-break she always planned to take in her 30s to concentrate on writing. What surprises me slightly, given her outrageous talent, is that it is very much a break, and she plans to return. Because, as she explains, becoming a full-time novelist “would really make me worry about taking risks in the way that I write, because if you do something that for whatever reason doesn’t pay off, that’s a few years of labour and a few years of income”. She would rather “time-box this and say: ‘This is something I’m doing for a while. It goes how it goes.’ I have fun with it and then I go back to what feels like real life to me.”