You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Nazneen Ahmed Pathak discusses her children's debut, new magic and British-Bengali history

Community lies at the heart of Nazneen Ahmed Pathak‘s middle-grade début inspired by British-Bengali history.

In 2013, Nazneen Ahmed Pathak had just given birth to her son. “I started to think about the fact that he didn’t have any stories that were about his identity and his heritage,” she tells me, speaking over video call from her home in Southampton.

Pathak’s son is third-generation British-Bangladeshi, and both sides of the family are from places very much connected to the British Empire. Prior to maternity leave, Pathak, a historian, had been working on a project about religious communities in the East End of London. As an area she knew well, she expected the work to focus on Muslim communities in the 1960s. “Immediately I became aware that the diverse communities that live in London have been there for hundreds of years.”

Communities of colour have, she explains, always been connected to the UK port cities through empire, slavery and colonialism. “When we start to look at those relationships, we begin to understand the idea of belonging in a very different way.” Her work revealed Bangladeshi seafarers, known as Lascars, who had been travelling in and out of ports around the world for hundreds of years. “In the 19th century, some men would jump ship in East London, marry local women, have families and settle.” This was alongside African and Chinese communities and Eastern European Jews fleeing persecution. “All these communities were living together in 19th-century London in a mirror of the way we live together now. I wanted to bring this to life in my story. It was an extraordinary moment for me, [discovering] that we had always been here.”

Empire tale with a twist

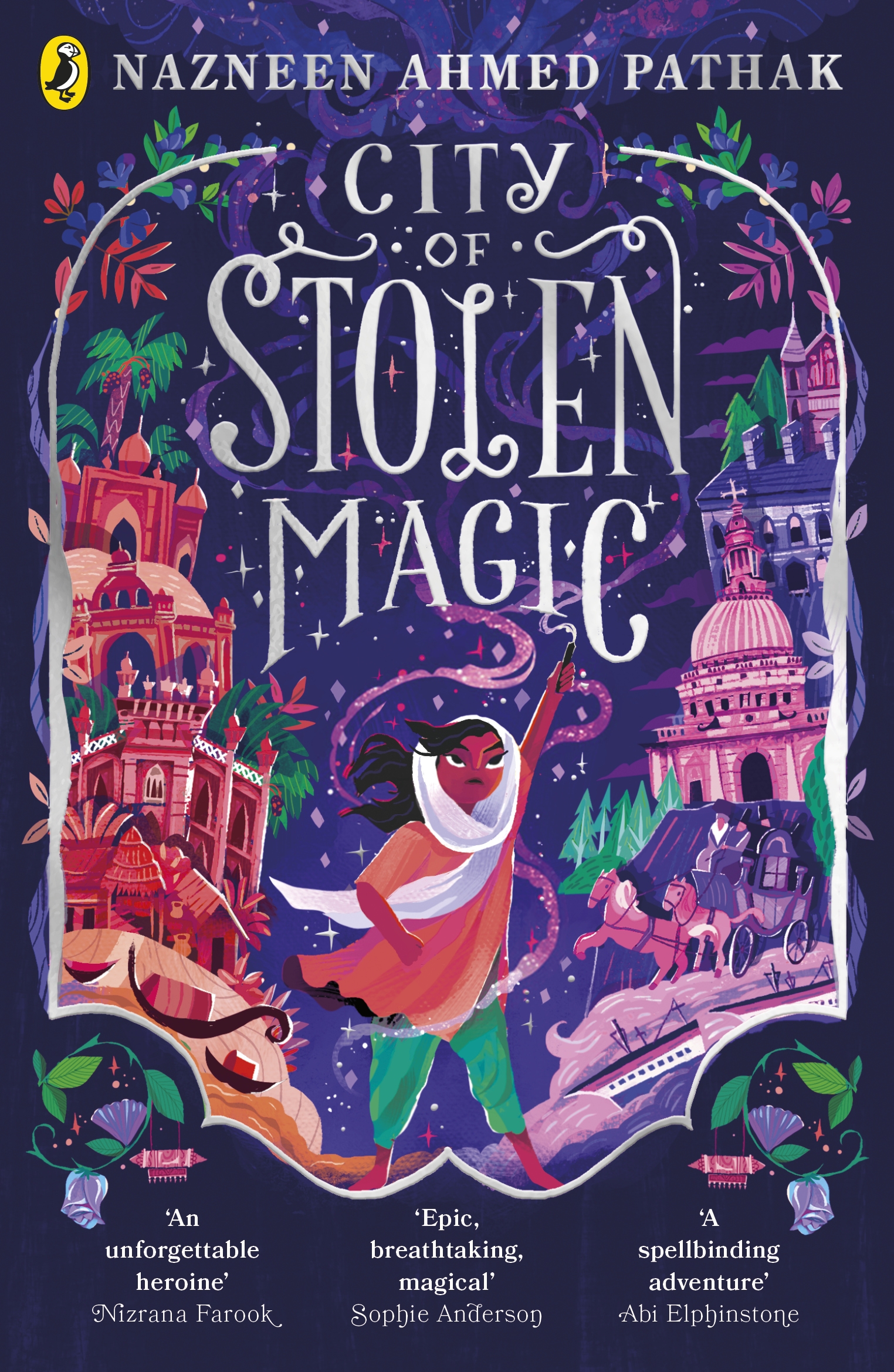

Pathak brings this history to life in her middle-grade début, City of Stolen Magic, which will be published by Puffin in June. The book begins in 1855 in rural Bengal, where we meet Chompa, a young girl in possession of a powerful, instantaneous kind of magic that she is forbidden to use. “Chompa is nosy, confident and wilful,” says Pathak, and the character eschews her mother’s “writing magic” which requires patience, precision and study.

There were spirits who lived in trees, amulets that could protect you, all kinds of aspects of magic and folklore that I did not see in stories

Chompa takes matters into her own hands—with terrible consequences; the all-powerful Company is drawn to her village, looking to abduct and sell magical people for their own profit. When her mother is taken, Chompa follows, first to the city of Dacca and then onwards to London, aboard a fabulous magical ship powered by a djinn. Along the way she meets friends and supporters, including other magical children. In London, Chompa realises that it is not only her mother who is in danger, but the whole magical community. “She has a much bigger challenge,” Pathak explains, “taking on the Company and this massive colonial system”.

The scope is epic and the adventure high-stakes, told against an incredibly rich and vibrant backdrop of life in 19th-century India and England. Pathak was also keen to draw on stories from her heritage and expand the “pointy hat” magic she saw in much children’s fiction. “There were spirits who lived in trees, amulets that could protect you, all kinds of aspects of magic and folklore that I did not see in stories.”

The idea of charms, pieces of scripture written as protection, was also powerful. “I was interested in that as a writer, as a way of building a magical world that celebrates writing as a kind of power and form of liberation.” But it was Chompa herself who drove the story. “She is such a dynamic character,” Pathak laughs. Inspired by Roald Dahl’s Matilda and Philip Pullman’s Lyra, the indefatigable Chompa has her own charm and presence in abundance. She also discovers that magic comes with a price, losing her hair part-way through the book. Pathak wrote this from her personal experience of losing her hair to alopecia universalis. “I wanted to seed it in there, that we don’t all have to look the same, that there might be changes in the way we look that we can come to terms with; that there is a core to us of who we are that goes beyond what we look like.”

Much of the City of Stolen Magic is woven around real-life people and events. The nefarious Company recalls the East India Company which ruled India; the Palace of Wonder echoes exploitative human exhibitions of people of colour throughout Europe in the 19th century. Lascar Sal was a real woman, married to a seafarer of Yemeni heritage, who ran a lodging house in East London. “She was jumping off the page demanding to be in the story,” Pathak recalls. “History is a treasure chest of stories,” she continues. “When we start to look at archives and look in the right places, we find so many extraordinary gems of stories we can use to make that period come alive.”

When we start to look at archives and look in the right places, we find so many extraordinary gems of stories we can use to make that period come alive

Scrutinising historical accounts and choosing which stories to tell presented the biggest challenge. Pathak often describes her writing as “embroidering untold stories”. “The Archive, with a capital A, is something that is arranged by white, middle-class men. There are so many stories, particularly of communities of colour, that we simply do not have.”

Bookish English childhood

Born in London, Pathak grew up in Surrey, a bookish child for whom libraries offered “a haven for peace, calm and mindfulness”. She wrote through her childhood but stopped at university. Her initial inspiration for City of Stolen Magic was stymied as she juggled work and early motherhood, returning to the story in 2016 when she was accepted to Penguin Random House’s WriteNow mentoring scheme. She describes this as a “serendipitous” moment which gave her the confidence to finish the book, and one that was invaluable in demystifying the publishing industry.

Extract

Chompa had always known she could do magic. She knew she could move and transform things, little things, if she focused hard enough and channelled that focus through her index finger. But whenever she raised that finger to show her mother what she could do, Ammi would fold her hand round her daughter’s and gently forbid it.

“You mustn’t, Chompa. It’s dangerous, and it’s not real power,” she would say, pushing Chompa’s book towards her. ”Please, learn your Farsi letters so you can help me write these charms.”

Letters. Why did she have to learn them when her finger-magic was so much faster, so much stronger? But Ammi insisted; and it was Ammi’s writing-magic that put food on their table. And so Chompa sat in the shade of the mango tree, grimacing and grunting as she bent over her book to make sense of the words in front of her.

On the left were the neat blocks of Bangla, all hanging from straight lines, with little curved tails underneath, and umbrella loops over them. Their meaning came clear and fast to her. On the other side of the page, though, was the slanting, looping lace of Farsi. It flowed like the river they lived by, carrying the meaning of the letters away from her before she could catch it.

How does she hope readers will respond to City of Stolen Magic? “I hope they take away this idea of a living London that is full of diverse characters… and that it starts to make them see that communities of colour have been here for a very long time. That’s what I wanted to bring to life, for my son, for all those children who had not known about this history.”