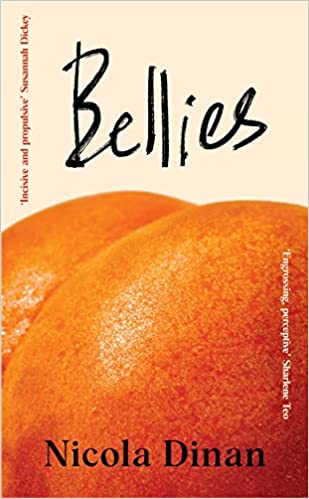

Nicola Dinan in conversation about her debut novel Bellies, subversion and fallibility

With a TV adaptation in the works, Nicola Dinan discusses her vivid, intimate début novel, Bellies.

Nicola Dinan, author of hotly anticipated début Bellies (Doubleday), began writing at a young age. “I think as soon as I became a teenager I was already writing stories, and to this day me and my childhood best friend still exchange fiction that we’ve written.” However, she tells me, speaking over video call from her home in Hackney, that this came to a “complete stop” while she was at university, reading Natural Sciences at the University of Cambridge, and in the years that followed as she trained to be a lawyer.

Looking back on that time, she says: “There was too much going on to really even think to put pen to paper, and I had become disconnected from this idea of using writing as a way to reprocess things I was going through. It wasn’t until a few years ago, maybe the year before I started writing Bellies, that I rediscovered not only the creatively written word but also that as a means to re-experience some of the emotions [I had felt] in a new, fictionalised way”.

Bellies begins as boy-meets-boy, giving the traditional meet-cute a queer twist, when awkward, self-conscious Tom encounters charismatic playwright Ming for the first time at a university party. Their attraction is instantaneous and, as the novel unfurls, we witness their relationship evolve. It traces their move to London, to embark on life together as young adults, and charts the ripple effect of Ming sharing her intention to transition. Against the backdrop of Kuala Lumpur, New York and Cologne, life’s vicissitudes play out and Tom and Ming are left to grapple with what those shifts mean for their relationship.

I wanted a messiness within each character and I do think offering both perspectives, and offering both perspectives where one is critical of the other, is necessary and helpful in achieving that

Dinan grants the reader privileged access to both sides of the relationship, telling the story in chapters written from Tom and Ming’s separate perspectives. What results is a wry, minutely observed coming-of-age that deftly captures the closeness, intensity and vulnerability of romantic love. This almost split-screen structural approach brings depth and complexity to the characters she has drawn. “I think by doing that it made it a lot easier to create two characters where neither was the good guy or the bad guy either. That moral complexity and dubiousness within each character was sort of necessary for the book. And not just Tom and Ming, I wanted the whole cast of characters to be equally fallible… I wanted a messiness within each character and I do think offering both perspectives, and offering both perspectives where one is critical of the other, is necessary and helpful in achieving that.”

Although dealing intimately with love, Dinan does not characterise the novel explicitly as a love story. She says: “I suppose it is a love story, but in a lot of ways it’s a subversion… It subverts the tropes of a love story in that Ming’s journey creates this fundamental incompatibility between Tom and Ming. So these two characters are left to negotiate what love actually is. That is the story: two characters negotiating what love can be between two people when other things are in the way.”

It’s not actually helpful to the cause to have these perfect characters, because when you create a solely virtuous narrative around a group of people, people look for ways to prove that wrong

As a trans woman, Dinan has her own experience of transitioning. In Bellies, she was keen to look at something “which is seen as so personal” from the perspective of someone one step removed. “I was interested in what it meant to be on the outside of someone else’s experience—and an experience that is deeply personal to them, like someone’s transness.” It was also important to her to offer a more pluralised view of queer and trans identities which, at times in fiction, can be relatively one-note. “[Ming] does things and you think, ‘Oh my God, you’re awful’ or, ‘You’re being awful in this moment’. But at the same time, just like the rest of us she is allowed to be...” Elaborating, she says: “There’s an impetus to create this virtuous image of a trans person who can do no wrong. I find that very limiting…I want trans people to have the freedom to be a bit shit too.” Instead she advocates for fully fleshed-out, authentic, multitudinous representation. “If we truly want to aim for fiction being an effective way to raise empathy for disenfranchised and marginalised communities, we have to write characters that are fallible. It’s not actually helpful to the cause to have these perfect characters, because when you create a solely virtuous narrative around a group of people, people look for ways to prove that wrong.”

Picture this

Dinan is in the process of adapting Bellies for screen after the TV rights for the book were picked up by Element Pictures, the production company behind “Normal People”, in a 15-way auction. She has found moving from prose to screenplay an “incredible experience” but not one without its challenges. “I think your tools as a screenwriter are perhaps more limited than they are as a novelist, because in a novel you construct the visual world to the level of granularity that you like. But with screenwriting, there’s something to the process which means you relinquish control over things like minute expressions on characters’ faces, or how things might look visually, to other people like actors and directors.”

The flip side is that this offers new opportunities for creativity, she goes on to explain, adding: “You’re working with different constraints and that means that certain arcs within each character change. Going into the project, it was so important for me to have a high level of fidelity between the book and the TV show. What I’ve realised now, having started on that process of developing the TV show, is that that level of fidelity which I initially envisioned just isn’t necessarily possible—and it wouldn’t necessarily make for a better adaptation.”

Extract

I got up from my chair and walked on to the grass. I stared back at the house. You could see clearly through the windows. The staircase leading up to my attic, and Sarah’s room. I wondered if people across the way watched us moving around like small figurines in a doll’s house, and whether they would notice we were gone. It was dwarfing that a place could feel so littered with my memories of it and yet have no visible trace of me. Flakes of skin, hair, fabric would all have fallen into the cracks of the wood and deep within the carpet, down into places where the sweeping bristles of a broom or the wheezing mouth of a hoover couldn’t reach. But even then, when the time came, that dark-green carpet would be ripped out and the floors replaced, and eventually our hair and skin would decompose, replaced by the hair and skin of whoever came after us.

Dinan is also currently working on a second novel, Disappoint Me, which has reached the third draft stage. She describes the process, which has been a very collaborative one and involved a lot of close work with her agent, as “fantastic”, noting the perspective that already having one novel under her belt has granted. The drive to put pen to paper once again was partly born out of a gnawing worry. “I think there’s been so much anxiety around Bellies [and a] sense of ,‘Oh wow, this is really my baby’. The only thing I could think of to try and [overcome] that anxiety was to write another book—and remind myself that there are always more words in the world.”