You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Nnedi Okorafor's 19th novel explores what it means to be human, and is her most personal yet

Katie Fraser is the chair of the YA Book Prize and staff writer at The Bookseller. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International ...more

Death of the Author explores how life and art intersect in a genre-defying tale.

Katie Fraser is the chair of the YA Book Prize and staff writer at The Bookseller. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International ...more

Nnedi Okorafor has always defied categorisation. When she first began querying publishers at the very start of her career, “They would say: ‘We don’t know what this is. We don’t know if this character is Nigerian or American.’ As if that matters. Why does she have to be one or the other?”

Speaking to me over video call from her home in Phoenix, Arizona, Okorafor continues: “In my early publishing days, this idea of Black characters on the cover was something that I had to fight with, because there was this general attitude that if there was a Black character on the cover, the book would automatically not sell as much. It was basically systematic racism.”

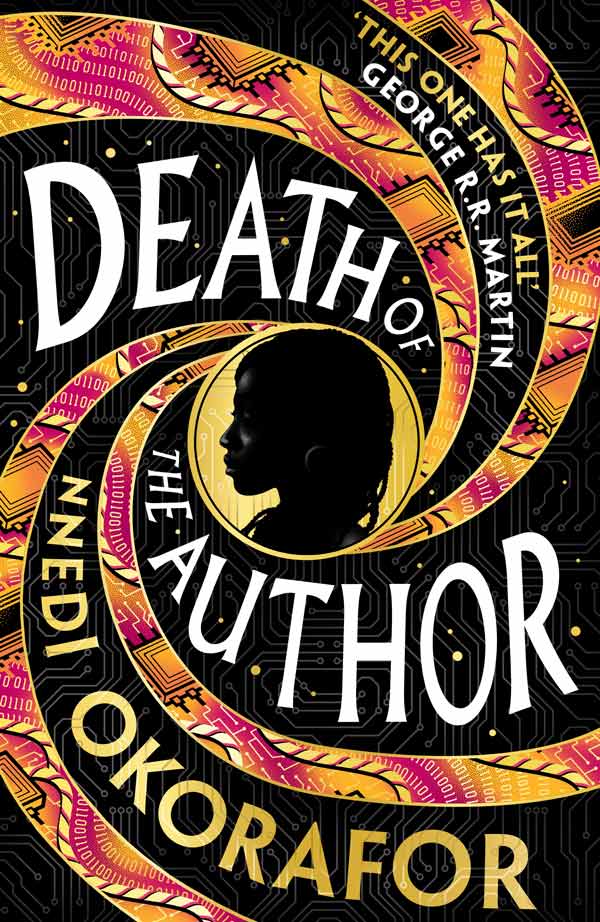

Now comes Okorafor’s 19th novel, Death of the Author, a magisterial book that is both expansive and deeply personal. Part SFF, part literary fiction, part family saga and part diasporic tale, the novel defies labelling. However, one of Okorafor’s “biggest worries” is that it will be pigeonholed: “I think when something is really complicated, people want to simplify it so that it’s easier to digest and so that they can kind of control the narrative. Something in me has been pushing back against that for years, and with each novel I’ve written the same thing kept happening. When you shove something into a box it doesn’t fit in, parts of it will fall out and those parts get ignored so people can focus on those things that are familiar to them. I’ve been frustrated about that for a long time. Part of me wanted to write something so unwieldy that you literally can’t shove it into anything.” She describes Death of the Author as a “Nnedi novel”, one that is “beyond the category”: a fitting line for a book rich in complexity and also her most personal work to date.

The novel follows Zelu, a paraplegic Nigerian-American writer who is struggling with her career. She has been fired from her job as an adjunct professor and her novel is going nowhere. Then, in the throes of despair, she alights on a new idea for a book set in post-apocalyptic, post-human Nigeria. The book, titled Rusted Robots, changes Zelu’s life. After landing a stellar publishing deal, new opportunities and new people present themselves. Namely, MIT engineer Hugo Wagner, who offers Zelu the chance to walk again, and Jack Preston, “the wealthiest man in the world”. In alternating chapters, Okorafor moves between Zelu’s narrative (set mainly in the US) and her relationship with her boisterous and loving family, interviews with Zelu’s family members and chapters from Rusted Robots. However, nothing is as it seems. “It’s made to be reread,” Okorafor asserts. “Especially when you get to the ending.”

When something is really complicated, people want to simplify it so that it’s easier to digest and so that they can kind of control the narrative

Zelu is “basically based on” Okorafor and, despite having previously written memoir and non-fiction, Death of the Author was “the first time I was like: ‘Okay, I’m shining a light on my family, on my life, and I’m not hiding behind anything with this one.’” She is “drawing from real moments” and, in the novel, the film adaptation of Rusted Robots is one such moment. The production company completely Americanise the novel. “Zelu had written her characters as holding African DNA... It was at the heart of the plot, just as much as the theme of humanity was,” writes Okorafor. The film is heralded as a triumph, but Zelu is incensed. “I went through a lot of things like that. I could speak on that because I know those things and I may have been battling them as I was writing Death of the Author. Life seeps into your art.”

The post-apocalyptic narrative follows Ankara, part of the “Hume” robot line modelled on humans. How people and technology are mediated by each other is crucial to the novel’s discussions on robotics, bionics and artificial intelligence [AI]. Okorafor did not pen Death of the Author in response to the ongoing AI debate but has “been thinking about this for a long time”, adding that: “Whatever AI has now—they are not self-aware. What they are creating is not art. You need self-awareness. You need experience, you need time.” The novel’s title, borrowed from the eponymous essay by Roland Barthes, in part references the role of humanity in a “world of automation”. Barthes’ essay “has always made me angry”, she says. “You can’t separate the author from the work. You can’t separate it and that’s okay.”

Death of the Author is dedicated to Okorafor’s sister, Ngozi Chijioke Okorafor, who died suddenly in 2021. The youngest of three sisters, and with a younger brother, Okorafor describes the trio as “like the Trinity, we moved in a unit”. Ngozi’s “unexpected” death “obliterated” Okorafor. “I was just untethered. I could not deal with it and the only way I could process it was to start writing. It just felt like it was time to tell the story. I started writing Death of the Author two days after it happened.” The result is a tender tribute to the intimacies of sisterhood as Zelu navigates life, its joys and hardships, alongside her four sisters. Ngozi is also the name given to one of the characters, imbuing the lines with a keening resonance.“I went home to Ngozi,” Okorafor writes.

Okorafor has written through trauma before, including “two other shocks”: her father’s death and “my whole thing with paralysis”. Following spinal fusion surgery at the age of 19 to help alleviate her scoliosis, Okorafor woke up paralysed from the waist down. “Writing kept me sane,” she wrote in a blog post in 2009. Gradually, she regained sensation, but would never return to her life before as a semi-pro tennis player. “It basically meant a death of who I was going to be. It changed everything. I discovered writing that way. I would not have discovered writing any other way. I was an athlete; I was very about the body and focused in a certain direction. The only thing that could have knocked me hard enough to look over ‘there’ was that personal death.” On the night of her father’s “wake keeping”, she began writing Who Fears Death. “One of the things I’ve always done from the time I first started writing, was writing through a trauma. My instinct is to put it on the page.”

Meditations on death suffuse Death of the Author, which asks how storytelling and memory interlink to defeat mortality. As the robot Ankara discovers, all it takes is for one person to remember and share their story. “I have come to understand that author, art and audience all adore each other,” Ankara thinks. “They create a tissue, a web, a network. No death is required for this form of life.”