You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

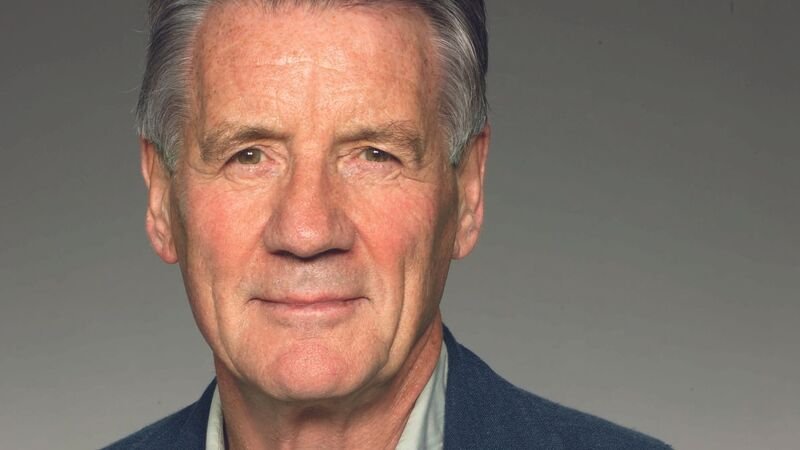

Michael Palin: Not just sand and camels

Veteran traveller and former Python Michael Palin returns to BBC1 this autumn with another epic journey in the vein of his previous series "Full Circle" and "Pole to Pole". The latest route takes him across the Sahara desert, travelling from Morocco to Mauritania and Mali, with a trip down the Niger to Timbuktu, and then on to Algeria, Libya and Tunisia. Weidenfeld will publish the tie-in, Sahara (£30, 0297843036), in September.

Of course any journey to the great desert had to involve camel trekking with Tuareg nomads in its vast dune landscapes. Palin found the emptiness of the Sahara rather congenial. "A landscape where there is nothing, or occasionally perhaps just one tree, really has a very strong impact on you," he explains. "You can't really believe that people live on the earth where everything has been stripped clean, stripped bare. You have a very odd sense of security in a strange way--there's not much going on, no noisy traffic or aircraft screaming overhead, no newspapers shouting headlines at you, no radio or TV stations trying to grab your attention with tales of horror and depravity. I'd quite like to own a little cottage in the middle of the Sahara."

Most of the time though, Palin's desert journey proved much more social. He visited the Polisario refugee camp in Western Sahara where the Saharawi people live dispossessed, barred from Morocco by a wall longer than the great wall of China: "You do see two sides of a country: Morocco seems so pleasant and full of sybaritic comforts, but it's got a hard edge like every other country."

He also stumbled across the Paris-Dakar motor race, a curious remnant from the colonial past, now "a big marketing exercise" for global business, in Palin's verdict. In Senegal, he watched a wrestling contest; in fascinating Mali, he witnessed ritual animal sacrifice.

Everywhere he travelled, he saw how the influence of the European colonisers remained strong. "It colours almost every agenda, even though most of these countries have been independent for 40 or 50 years. For a lot of them the modernisation just sort of stopped at a certain point, like in Mauritania and Mali. Tunisia was the only country I visited where I felt there had been an unbroken passing-on of the baton. It's the only secular Islamic country in Africa, and some would say it's in a much healthier state than any of the other countries. But that's a judgement about what health is, and I'm really not sure.

"The more I travel the more I believe you have to look at some of these countries and then look at your own, and say, 'Is this honestly the best we can do?' The environmental disaster, the mess we make of our own lives, people getting a million pound pay-off for ruining a company--how can we honestly say, 'Come on Africa, this is what you should shape up to?'"

Not surprisingly, in Libya Palin's visit was carefully stage-managed by suspicious officials, while in troubled Algeria, in the wake of 11th September, he needed round-the-clock protection. But again, he found his experiences of the country resisted the stereotype: "We were warned against going to Algeria; obviously you have to be careful, but I think you can overplay the danger. Because, as far as I know, Algeria is 99.9% occupied by decent, honourable people raising families, trying to educate their children and wanting to be part of the modern world. You just feel there is a huge reservoir of good will in these countries; they want to get out of the despair they have been dragged into."

Palin says he has always resisted taking a political angle in his travel series, preferring to concentrate on simple encounters with local people. "To me a short encounter with a family in a tin shack in a town in northern Mauritania, with all the problems of language, is more exciting than endless tours of mosques," he explains. He particularly loved his evenings in the desert, he says, sitting by the campfire with the group of Tuareg nomads who acted as his guides, undergoing rudimentary language lessons amid a lot of laughter.

But the Sahara journey forced him into an unusual degree of reflection. "The last leg of the journey involved coming back to Gibraltar, and hearing about some of the people who had died trying to get into Europe from the Sahara, crossing the Straits in tiny boats. I felt that when I came back, especially in Gibraltar, there was this fear of change and these barriers going up.

"What I found during the trip is that it's important to look round and see who's out there, and find out more, not less, about other countries. In that way it becomes much more difficult to feel anger and hatred and bitterness towards people, because you realise who they are and where they're from."

Benedicte Page