You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Obioma Ugoala discusses the intersection of masculinity, racism and sexism in his new book

Natasha Onwuemezi

Natasha OnwuemeziTasha Onwuemezi is associate editor of The Bookseller and a freelance writer and editor.

For Obioma Ugoala, exploring how masculinity intersects with race and sexuality is vital for societal progress and understanding.

Tasha Onwuemezi is associate editor of The Bookseller and a freelance writer and editor.

When I first meet Obioma Ugoala, we are at The House of St Barnabas, judging one of the British Book Awards; we are both on the panel for the new Discover Book of the Year. What strikes me is that Ugoala—who is affable, funny and articulate—really puts in the work. Alongside starring as Kristoff in “Frozen” on the West End, following a turn in “Hamilton” as the George Washington (a.k.a. the best character in the history of musicals), Ugoala has also read every book on the shortlist, made thoughtful pre-panel notes about each one and participates in the discussion with passion and consideration. I say this because it might be tempting for someone with such a busy schedule to phone it in, but that’s not Ugoala.

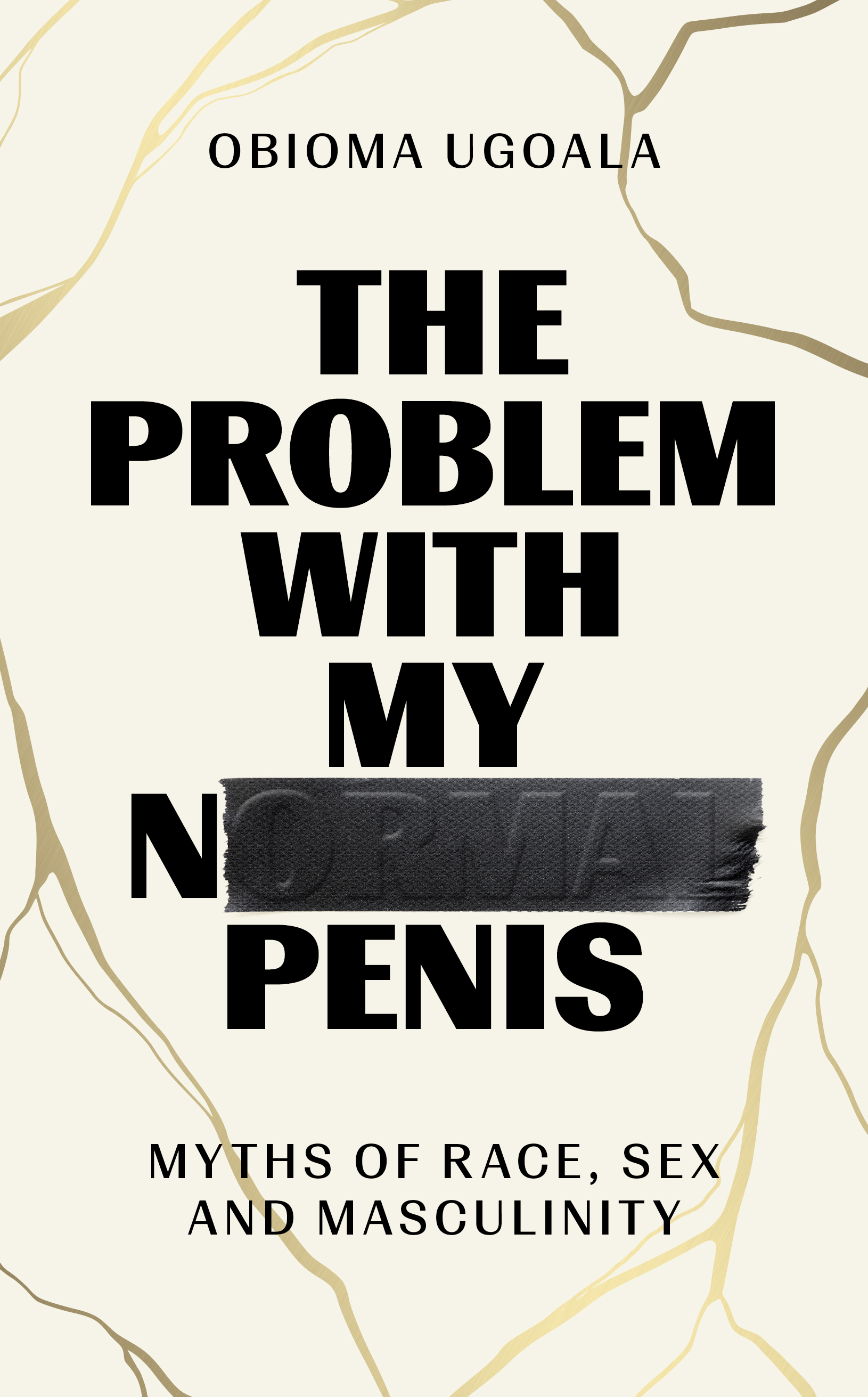

For the past few years, Ugoala, who is of Nigerian and Irish heritage, has been focusing this work ethic on writing the book that would become The Problem with My Normal Penis, an exploration of masculinity and how it intersects with race and sexuality. While the idea of the book had been “percolating” in Ugoala’s mind for a long time, the seed really sprouted from a conversation he had in 2018 with a Black actor, who one day at dinner, asserted that Black men have a higher sex drive than white men. Ugoala was taken aback by this statement, because even at this early stage, before he started researching the book, he knew that “the idea of the hypersexualised Black man was something that had its origins in slavery and in colonialisation and in trying to justify the abhorrent acts of the transatlantic slave trade and the foreign policy from Western powers”.

But the actor would not let it go. “For him,” Ugoala says, “his sense of self was very much rooted in this idea of, ‘In a world where I might be denied equal access to education, employment, justice and fairness, in this game of life, on my starting position as a Black man, I might have minus two on those characteristics, but I get plus two on my sexuality.’ And for a world that exalts a man who is successful with the opposite sex, he didn’t want to give up that plus two, no matter the taboo or negative origins of that [narrative], because it was such a part of his identity.”

I’m a big believer in if you want to change the world, you start with yourself first

This was enlightening for Ugoala—and surprising for me because, when we discuss this incident over Zoom for this interview, I at first assume the actor in question is white. “It’s not always only white people who believe [these anti-Black narratives]; it’s not only straight people who believe homophobic narratives or men who believe misogynistic narratives,” says Ugoala. “Even though he was Black, [this actor] had internalised an anti-Black narrative.” And this is where we come back to putting in work. After this incident, Ugoala was determined: “So I thought, ‘Maybe I can’t convince you’, but I’m a big believer in if you want to change the world, you start with yourself first. So I started with my own journey of questioning: if I was going to be critical of this man, how much of my own narratives had I learnt? How dangerous were they and how could I begin to unpick them?”

Starting the process

Thus began Ugoala’s deep dive into how Black men exist within a racist patriarchy and the degree to which our societal idea of masculinity is rooted in racism, misogyny and homophobia. And also, most importantly, his exploration of how to expose and dismantle these narratives to ensure they are not passed down to the next generation. While the title of the book was one of the first things put to paper, the subtitle of the book, Myths of Race, Sex and Masculinity, surprised Ugoala. “I knew that my idea of racism, as experienced as a Black man, was connected to the fact that I’m a mixed-race man in some sense. I knew that sexuality and homophobia played some role in my construction of the idea of masculinity, but I don’t think I had ever really connected how none of these things exist in a vacuum,” he says. “As much as it’s a discussion about black masculinity, it’s as much about a discussion of masculinity as a whole and how we all, as a society, interact with that.”

The interconnectedness of these aspects is vital to the understanding and progression of society when it comes to dismantling misogynistic, racist and patriarchal structures, says Ugoala. “What’s dangerous is if we do try and take these things in isolation, then we end up with this very odd notion in trying to say that [police officers recently convicted for murder] Wayne Couzens and Derek Chauvin are outliers, when they’re very much more products of our society... that is an uncomfortable truth,” he explains. “What’s really tricky is that as a society we would prefer to have one or two outliers than for all of us to do the necessary work to say, ‘Actually the way that I treat you as a woman is potentially a bit problematic, my expectations of my wife in the distribution of household chores are potentially problematic’. That is more uncomfortable, and we would prefer to sacrifice one Wayne Couzens and go, ‘We’ve done the work’, than to go, ‘Hey listen, we all need to constantly be in work; we all need to constantly be asking questions, constantly saying, “Can we do better?”, constantly engaging in what it is to be human.’”

As an artist, my only aim is to leave people slightly moved as they leave the theatre—the same goes for my plays as it does for this book

Ugoala highlights some shocking data that underscores the importance of us all doing this work. “When someone is constantly challenging you and asking you to do better, you get tired,” he says. “It is tiring, but it’s necessary and vital work because eight out of 10 women who are sexually assaulted know the person who sexually assaulted them. So it isn’t an outlier, it isn’t one or two particularly perverted people—these are our friends, neighbours, brothers, uncles, colleagues, and we need to have those necessary conversations, not only to protect women from becoming victims of those people we know, but also to protect those men from doing these gross, horrific things.”

Stage plight

As a mixed-race actor working on the West End, Ugoala has received backlash and “gross messages”, particularly about his casting as Kristoff in “Frozen”, who was originally white in the Disney film on which the musical is based. If you can believe it, this year a group of audience members actually walked out of a performance over his casting. “I know that this doesn’t need to be said but in a world where you can have a talking snowman or a queen who can turn everything into ice—this is the thing that’s concerning you? Okay. I’m sorry,” Ugoala says. “There are six-year-olds in the audience who watch it with an openness, with a desire to be entertained. But because [these people] have been wounded, they have wounded themselves, they cannot access that level of openness and I think that’s sad.”

Extract

Far too often I am aware of my position in predominantly white spaces as a man of dual heritage, and the predicament it puts me in. If I am a passive observer to certain charged conversations, I am accused of denying my race and heritage and having my tacit reaction read as non-verbal approval. If, however, I am moved to reply, I have alternatively been accused of ‘getting too confrontational’, ‘making everything about race’ or, my personal favourite, ‘playing the race card’. Secondly, there was this older actor’s presumption of my willingness to leap to violence. Half-goad, half-threat, it was a hopeless attempt to paint me as either a coward or a bully. Allowances are often afforded for comments made under the influence; after all, I had been called worse by much better. It was the specificity that stuck in my ears, from the size of my genitalia, to my dating preference, to the crudeness of the language. These were not witty put-downs, nor were the comments borne of any first-hand observations. Race, as so often happens, had come bounding into the room as we two men swung our proverbial manhoods around.

Emphasising his reasons for exploring these topics in the book, Ugoala continues: “If after reading the book, or having been asked these questions, people decide to carry on living exactly how they want to live or leave completely unmoved, that is entirely up to them. As an artist, my only aim is to leave people slightly moved as they leave the theatre—the same goes for my plays as it does for this book. Maybe somebody sees something from a slightly different perspective, and if they do, mission accomplished.”