Olivia Laing on unearthing the sinister secrets of gardens

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

In Olivia Laing’s new book about the worlds to be found in a walled garden, the author helps us glimpse utopia

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

"Inside a garden is a very rich place to think about politics and society.”

It’s the last week of February and Olivia Laing’s enchanting walled garden behind their Georgian house in Suffolk is filled with signs of the coming spring: a budding magnolia; a daphne tree in fragrant flower; a beacon of a bright red anemone just unfurling into bloom.

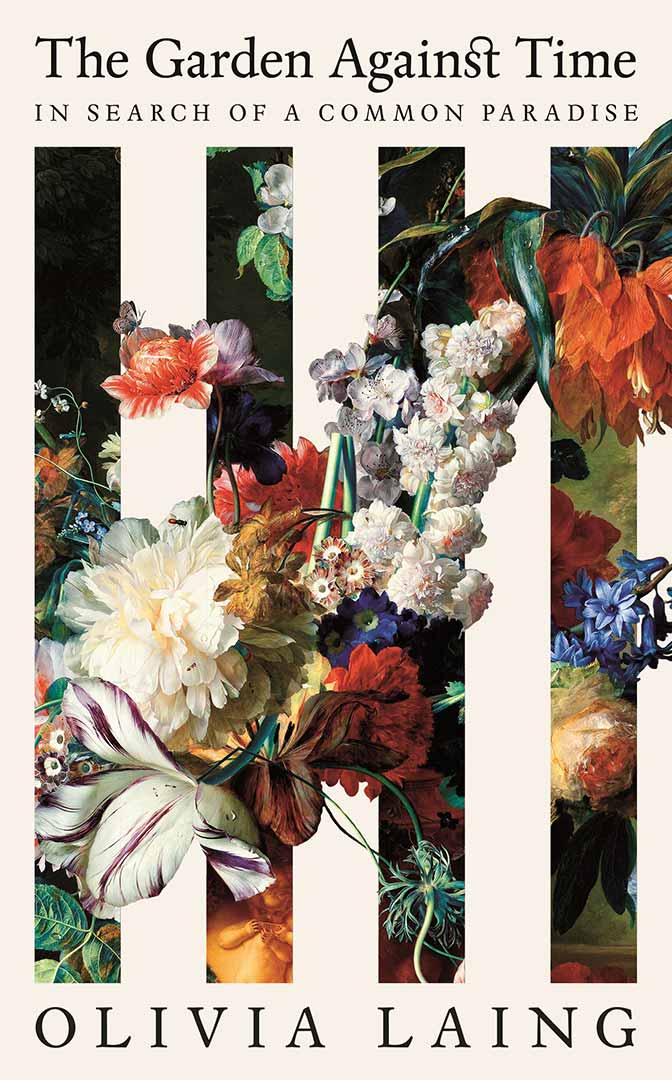

The current garden was originally laid out from the 1960s by a previous resident—the distinguished award-winning gardener Mark Rumary—but then fell into a state of neglect for some years before Laing and their husband, author and Forward-Prize winning poet Ian Patterson, moved there in 2020 and began to restore it. “More than anything I wanted this garden to be mine,” writes Laing of seeing it for the first time. The beguiling story of its restoration provides a kind of supporting trellis for the many branching themes of Laing’s new book, The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise.

“I loved gardens right from the beginning,” Laing tells me, curled into a chair in their yellow sitting room which looks out over the garden. “My earliest memories are of being fascinated by plants as I walked to school and nursery.” And a childhood that was often challenging led to what Laing describes as a “permanent, nagging need for a place that was safe, wild, messy, bountiful and above all, private”.

So now, as the owner of a secret garden completely hidden from the street outside, it would have been easy for Laing to dwell rosily on it as a place of refuge from the world and its messes. Instead they write: “The lockdown… made it painfully apparent that the garden, that supposed sanctuary from the world, was inescapably political”. Accordingly The Garden Against Time challenges us to confront the ways in which gardens have so often failed to be paradises they ought to be by definition. For the very word “paradise”, Laing explains, has its roots in Avestan, a language spoken in Persia 2000 years BCE, and derives from the word pairidaeza which means “walled garden”.

We’re not going to survive the climate emergency unless we completely, drastically rethink our ideas about nature

“Even a walled garden isn’t actually closed and separate from the world because every plant has a long history of cultivation by humans. I wanted to draw correspondences with the much broader history of gardens, how they are created and who has access to them.

“One of the things I was stunned by was that while garden ownership and garden access is more prevalent in Britain compared to other countries, it’s very much along class and race lines. I was writing the book during the pandemic when there were such intense issues around access to public space. The people who owned private space luxuriated in it, and the people who relied on public spaces couldn’t get into them.”

Slavery profits

An even darker side to the creation of private paradises, Laing shows, is the fact that many of this country’s most beautiful gardens, including those at Suffolk stately home Shrubland Hall close to where they live, were financed by immense profits from slavery. Then there were the successive parliamentary enclosure acts in the 18th and 19th centuries that deprived ordinary people of the right to cultivate common land, “creating a landscape of power, stripped of its human element”, as Laing puts it. A prelude, they also point out, to the fact that half of the country is now owned by less than 1% of the population.

But just as private gardens can be shameful or selfish spaces, The Garden Against Time explores how they can also provide us with a metaphor for better ways of living; for creating a paradise open to all. Laing highlights the ideas of such figures as John Milton who in “Paradise Lost” uses the model of horticultural cultivation as a way of considering good government; poet John Clare and his reverence for wild flower species and what we would now call biodiversity; and William Morris who “believed it was everyone’s right to live in beautiful, unspoilt, unpolluted places”.

Says Laing: “I think it’s going to be very interesting doing events for the book this summer and talking about utopian socialism at a time when we’re potentially going to have a change of government. Such ideas are ripe for re-exploring and in fact vitally necessary—we’re not going to survive the climate emergency unless we completely, drastically rethink our ideas about nature.”

Continues...

Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency

Picador, £9.99, pb, 9781529027655

“Laing writes in a winning, passionate voice that proves both soothing and galvanizing, especially amid a panic… It’s not just art we need in an emergency, but writers, like Laing, who gently guide our eyes to what’s out there”, said the Observer.

14,836 copies sold

Long before they moved to Suffolk, such ideas were already preoccupying Laing, who has created gardens throughout their adult life despite not becoming a home owner until their 40s. “In very unlikely places too—on pig farms, and while living in all sorts of very temporary accommodation,” they laugh. Later, inspired by celebrated filmmaker and gardener Derek Jarman’s writing about herbs in his book Modern Nature, Laing studied herbal medicine. “It was an education that opened up the natural world for me in a way that perhaps nothing else would have done.”

Many serendipities spurred the writing of The Garden Against Time; for example the discovery that Goodwyn Barmby, a utopian socialist who visited Paris in 1840 and brought the new word “communism” to our shores, had visited the garden; his sisters later came to live in this very house after his death. “Discovering that was just mind-blowing,” Laing says. And after befriending their new next-door neighbours John and Pauline during the pandemic, Laing was able to commission from 92-year-old retired modernist architect John, the delightful line drawings which decorate the text. The book is dedicated to his now late wife Pauline.

Completion

Laing tells me that the publication of The Garden Against Time marks the completion of a loose Dante-esque trilogy which also takes in two of their previous non-fiction works. “The Lonely City is about the purgatory of being behind glass and not quite making connections; while Everybody is a descent into Hell; a very austere book about all the ways in which people lose their freedoms because of the kind of body they are inside. And then The Garden Against Time is about the joy and beauty of paradise as well as its more sinister aspects. I wanted the book to feel like a place that anyone bruised and battered by the last years of political turmoil could pull back to for replenishment. Not so as to create idylls of our own and ‘screw everybody else’, but in order to think about how we might change the society we live in for the better.”