You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

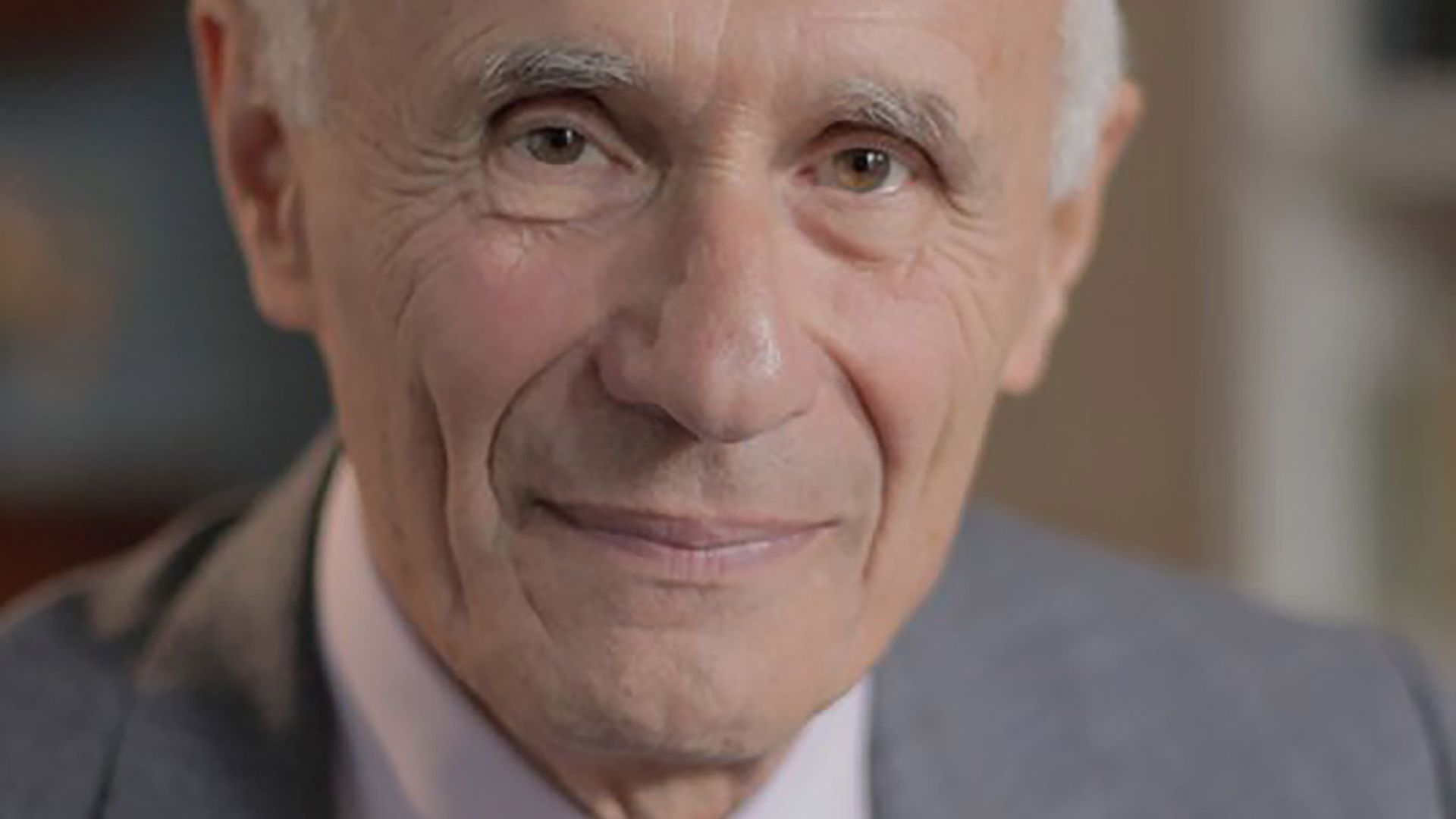

Peter Lantos talks about his remarkable survival and his story of hope

Charlotte Eyre

Charlotte EyreCharlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed the

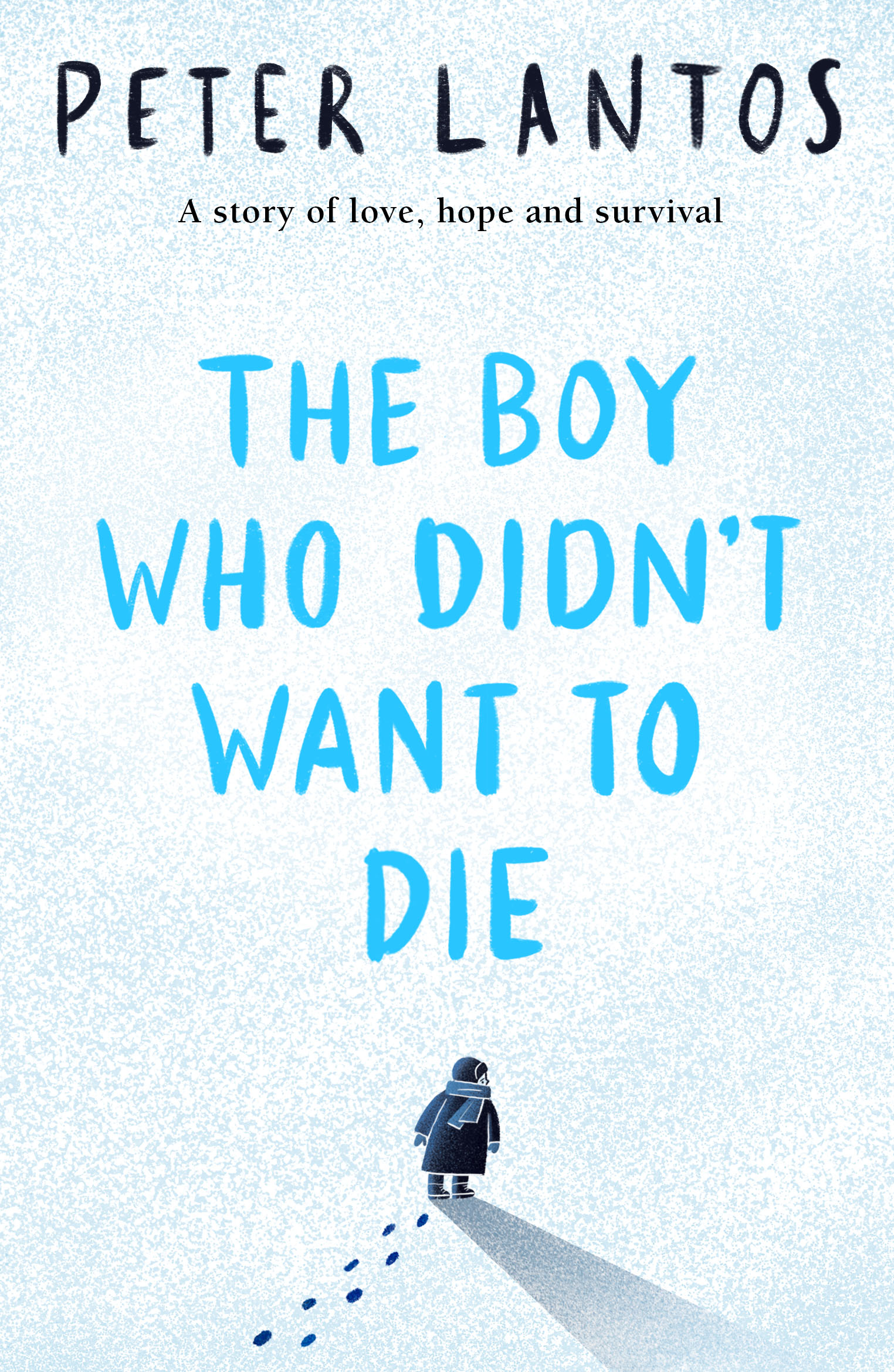

...moreHolocaust survivor Peter Lantos has mined his remarkable history to create a book for young readers that he says is not about death, but about survival against the odds

"In a few years’ time I won’t be around to tell this story. I’m one of the last generations of survivors and it is highly unlikely that many survivors of the Holocaust will be alive in 10 years.” Peter Lantos, a respected neuroscientist and author, thought he had a “moral obligation” to write The Boy Who Didn’t Want to Die, his soon-to-be-released account of how, during the Second World War, he was deported from his childhood home in Hungary to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, and how he survived, eventually defying the Communist authorities in his country, coming to the UK and becoming a British citizen.

The story starts with Lantos coming up to five years old. Like all children, he enjoys playing with his cousin and eating some of his favourite foods, in this case “krumpli paprikas”, a dish of potatoes cooked with red pepper. His family runs a timber yard and has a fairly comfortable life, but in 1944 Germany invades Hungary and the family is split. First of all, Peter’s older brother Gyuri is sent away to do hard labour, then the rest of the family moves to the ghetto. They are later put on to trains that take Peter and his parents, after being separated from his aunt and cousin, to a concentration camp.

When I tried to go back and remember, the physical hardships were quite obvious

Lantos is skilled at telling the story about what happens, but also conveying a young child’s level of comprehension about the situation. In chapter one, the governess Maria has left because the family is Jewish, and Peter’s father later explains that Hitler wants to murder all of the Jewish people in Europe—but the young Peter doesn’t really understand. “I had to suppress my thoughts as an adult and think, ‘What was it like when we were told that we had to leave our house?’,” says the author.

“I wanted to tell it as a simple story of a journey which gradually becomes something different.”

Once the family is in the concentration camp, life becomes very hard very fast, and his father, who exchanges his bread for cigarettes, dies of heart disease. It is the physical deprivations that Lantos remembers most, the constant hunger and the freezing cold, as well as seeing people dying. “For a child it was a terrible thing to be taken from a reasonable, middle-class home into a ghetto, and then to a concentration camp, then having endless journeys without much food and drink… When I tried to go back and remember, the physical hardships were quite obvious.”

The journey to freedom

Half-way through the book, British soldiers liberate the camp and Peter and his mother spend some time in a nearby village, where they befriend a GI called Henry, and soon decide to make the long journey home, on multiple trains, to go back to Hungary and find their family. Tragically, many relatives did not survive: the part where Peter and his mother find out that his brother Gyuri died in hospital is one saddest sections of the book. They also learn that his beloved cousin and aunt were murdered in Auschwitz and not long after, at a memorial service at the synagogue for those who died in the war, more names were read from Lantos’ family than from any other. In total, 21 had perished.

Life is not always easy for the people in the story following their release from the concentration camp—Lantos talks about a young person who dies because they cannot cope with the food that is now freely available, for example—and I wondered whether he wanted to show how things were not easy for Holocaust survivors, in case children have a naïve idea that life was hunky-dory as soon as the camps closed. But when I ask him about this, he says that this part of his life was full of hope, starting with when he began school in 1946, which is something he wants young readers to understand.

Hatred is a negative sentiment, which destroys the person who hates rather than the person the hatred is directed at

At school, he was a talented mathematician and tried to emulate his brother, who had always been outstanding academically, and in his teens he decided to study medicine so he could help people. He “didn’t have time” to feel sorry for himself. Surviving Belsen gave him a “kind of strength” and a sense that “if I can survive this I can survive anything”.

He made a conscious decision to try to understand what had happened in Germany and at school chose to study German, which wasn’t obligatory. Later on, he even spent time as a medical student in the German Democratic Republic and befriended German medical doctors. “Hatred is a negative sentiment, which destroys the person who hates rather than the person the hatred is directed at… although of course I did sometimes wonder, ‘What did your father do during the war?’”

A passage to the UK

The book also talks about how Lantos came to the UK as a junior doctor in 1968. The communist authorities gave him permission to leave Hungary for one year, and one year only, but he decided to defy them and stay. His heroic mother had passed away several months prior and coming to England felt like breathing fresh air, where he could say or do whatever he liked. He found British people to be “very helpful” and the Home Office had no problem with him staying. He was sentenced to 16 months in prison by the Hungarian authorities in absentia, so was not allowed to visit his homeland for many years after, and his belongings were confiscated. But he never had any regrets—he would still choose to live in the UK over anywhere else. And this year he was made an honorary freeman of his home town, which was a pleasing counterpoint to this part of the story, he says with a smile.

Scholastic will publish The Boy Who Didn’t Want to Die on 27th January 2023, the International Day of Commemoration for the millions of victims of the Holocaust, and Lantos will continue his work of many

years standing in visiting schools and talking to young people about his childhood. “I thought I should tell children what happened and having a book like The Boy Who Didn’t Want to Die is very different from reading a chapter or a few paragraphs in a history book,” he says. And, it ends on a positive note. “It’s a book, not about death, but about survival.”