You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

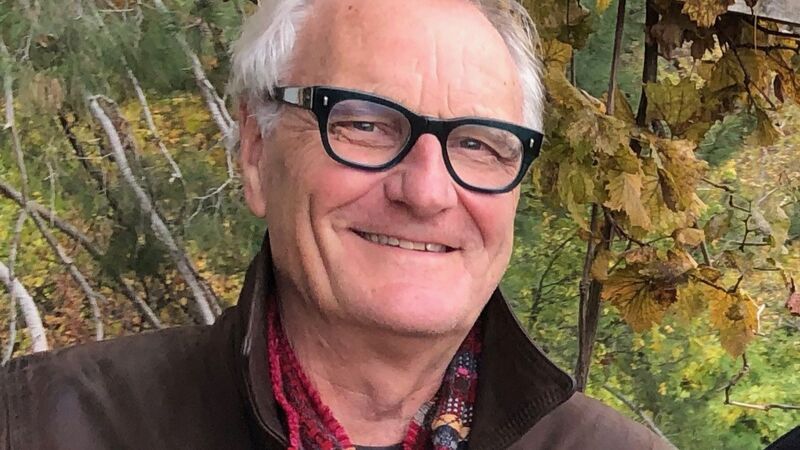

Polly Crosby’s new dystopian YA novel reflects on the way society treats people with disabilities

In Polly Crosby’s The Vulpine, illness and disability are prohibited – and “imperfect” children are being stolen away by the Vulpine, strange fox-like creatures who live underground.

“During Covid-19, I had to stay in my house because I was potentially one of the people who could have died.”

Polly Crosby, the author of the soon-to-be-released Young Adult (YA) novel The Vulpine, out in January, is reflecting on how powerless people who have chronic conditions such as cystic fibrosis, like she does, can feel.

“At one point, [the pandemic] was rushing through care homes, but then the government decided it could afford to fund new medication for some people with cystic fibrosis that would keep them well enough to potentially not die from Covid-19. Somebody ticked a box and said: ‘Yes, you will live,’ [but up to that point] it’s really frightening because the power is taken out of your hands.”

Crosby’s reflections on her position in society, and society’s reaction to people with disabilities or chronic conditions, fed into The Vulpine, a thrilling dystopia where illness and disability are prohibited. In the novel, any children who are classified as “imperfect” are sent to “the Hospital”, a government-owned entity where they can be “looked after properly”. But there are rumours that some of these “imperfect” children are being stolen away by the Vulpine, strange fox-like creatures who live underground. Orla knows about the Vulpine from a storybook hidden in her mum’s study, so when she discovers that she has a lung condition that her parents have hidden from her, she decides to find out whether the Vulpine are really as monstrous as they have been portrayed.

It turns out that the Vulpine are not (spoiler alert) a group of monstrous creatures, but are instead an entity that protects the vulnerable, including a girl recovering from cancer and a baby with Down’s syndrome. The question then, of course, is what the Vulpine are actually trying to protect these people from.

We don’t have to look too far back into our own history to see children with disabilities being removed from their families. Even now, society isn’t perfect, and while there are people who champion disability and make everyone feel welcome and included, there are others who feel they can discriminate “loudly and proudly”, says Crosby. “That’s quite frightening when you’re in my position.”

The 21st century is also throwing up new ethical dilemmas when it comes to disability, and now genetic testing is something that societies are starting to grapple with.

“I am fascinated by the ethical and moral implications of this,” Crosby says. “Is it okay to try and change yourself, however far this takes you, because in the end, you’re only potentially harming yourself? And with medical science, should we be trying to erase all illness or disability when it is often part of someone’s identity? Should we abort babies when we know they will have certain life-limiting illnesses? And if the technology comes along to actually take away someone’s disability, how will they feel with this part of their identity stripped away?

“I know my own cystic fibrosis has made me empathetic, mindful and above all, resilient. Who should have the right to make these decisions and where do we draw the line? At the end of the day, if we were all the same, the world would be a very dull place indeed.”

Crosby’s career as an author is something she wanted for a really long time. She wrote her first published book, the adult novel The Illustrated Child over a period of 10 years while she had a young child (and was living with cystic fibrosis, which is a job in itself).

Should we be trying to erase all illness or disability when it is often part of someone’s identity?

There were several agents interested in working with her, but she had her eye on Juliet Mushens, her “dream” agent, and held out until she was able to persuade Mushens to read her work.

“I had a couple of offers of representation, and each time I emailed Juliet to let her know,” she laughs. Her persistence paid off.

Crosby has subsequently written three more books for adults and her first YA, This Tale is Forbidden, was published in January this year by Scholastic. The Vulpine was edited by Scholastic’s Julia Sanderson, who did an “amazing” job in helping to shape the story, Crosby says.

“She was able to help me work out what I should and shouldn’t be saying and how I should and shouldn’t be saying those things… I wouldn’t have been able to do it without her.”

Writing for teenagers is extremely rewarding, Crosby says, even though it is harder than writing for adults. “They know if you’re being genuine and you have to be so careful about every word and every idea that you are trying to convey. Because I remember those books—the books I read when I was 16—and they’re the ones that have stayed with me forever, more than any other book.”

What she didn’t see growing up, however, was a book that was truly representative of disabled people. She didn’t read a book with a disabled heroine or hero or even someone that was unwell unless their illness or disability was a plot point, and that is “really sad”, she says.

If someone has an illness or a disability, that is only a “small part” of every person. “When you see someone with cystic fibrosis on television or in a film or in a book, it’s normally because that someone is dying. That’s really sad, because there’s so much more to us.”

The Vulpine shows a society where its citizens push for so-called perfection, where illness has been eradicated, but as Crosby points out, success can be measured in so many different ways.

“I wanted to write about difference, not just difference in terms of disability, but how people need to be aware of other people’s differences. Everyone has something to bring to society.”