You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

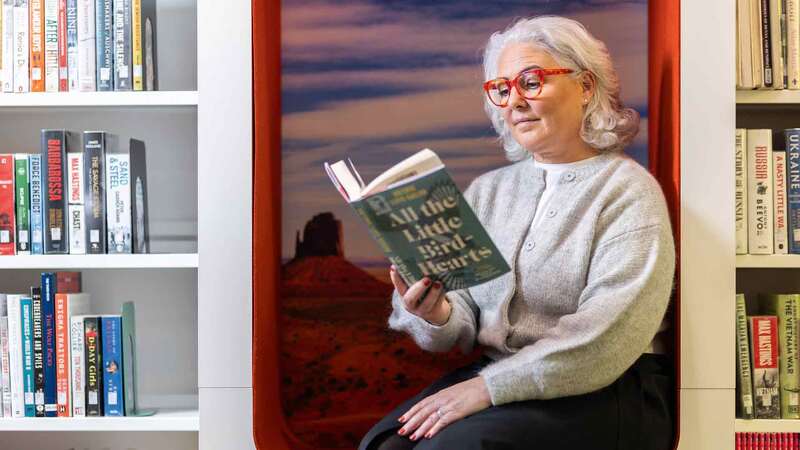

Holly Smale | 'The books you love at that age stay with you forever'

Moving on from Geek Girl was "emotional. It was painful, but I was ready," Holly Smale tells me when we meet at her publisher’s offices in central London. The teen model series was a bestseller on release and has sold, to date, more than 3.4 million copies across the globe in over 30 languages. "I spent 10 years of my life with this girl, who started out feeling like my little sister and ended up feeling like my daughter." But by the time she wrote the final Geek Girl book, the Valentine sisters, stars of her new series, were already in her head. In the Geek Girl series, protagonist Harriet was an ordinary girl given an extraordinary life, which Smale says "is what teenagers are fascinated by". Her new series flips this concept. The girls in The Valentines series have been born into that extraordinary life. "How do they find ordinariness in that? How easy is it to deal with all the things they’ve so desperately looked for?"

The Valentines are one of the most famous families on the planet, a glossy dynasty of movie stars who appear to have everything. There’s a film star mum, director dad and vlogger brother Max, but each book will follow the fortunes of one of three sisters, Hope, Faith and Mercy. Happy Girl Lucky is told from the perspective of 15-year-old Hope, the youngest sister. Hope’s voice feels immediate and genuine, an appealing mix of vulnerable, naive, sweet and hopeful. She’s led a cosseted life, but she is lonely and longs for love, dreaming of her romantic "lead".

Each chapter opens with a film script, Hope’s idealised scenarios of how her life will pan out. "It made sense that she was constantly casting herself in a film. We’ve all done that and teenagers definitely do," explains Smale. It’s a neat device that not only shows us how Hope’s mind works but also provides much of the book’s humour. "Not only is she very bad at writing films," Smale laughs, "there’s also the comedy that comes from the reality stepping in." Like Geek Girl’s Harriet, Hope is written in the first person and I ask Smale how difficult it was to create a distinctive voice. Hope was inspired by a reader, "very sweet, optimistic, maybe not that academic", and the voice, she found, was already in her head and came relatively quickly.

Subsequent books will be written in Faith and Mercy’s voices. "I’m really enjoying being able to show the sister dynamic from different perspectives," says Smale, who has long been fascinated by siblings. She’s close to her own sister and adored literary siblings as a child. The Fossil sisters in Noel Streatfeild’s Ballet Shoes were one of her original inspirations for the Valentines, and she was "obsessed" by Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. "It can be such a complicated dynamic. You love them, you fight with them, you can press their buttons like no one else can."

Cultural ideals

The theme of filtering and editing is woven through the narrative. The first few chapters present the Valentines as a shiny, happy ideal. Smale sees this pursuit of perfection, fuelled by social media, as increasingly prevalent among teenagers. "They’re expecting their lives to be perfect, to work the way everyone else’s does, according to what they see on the internet or in the films they watch." At the same time, she says, it’s incredibly unfair "that we give girls these cultural ideals and then slam them for wanting it". Hope’s journey is very much about learning to unpick her filtered version of events; a more complex reality is slowly unveiled and readers will discover more layers in later books. It is Smale’s way of saying, with a gentle hand, "that everything isn’t going to be perfect. You can aspire, you can dream, you can hope, you can stay positive, but let the negative in too."

That same pressure applies to relationships. Harriet and boyfriend Nick were aspirational; here Smale "wanted to give readers a contrast". Hope’s arc with love interest Jamie may, she admits, come as a surprise to Geek Girl fans. After a movie-perfect week in London, the tone shifts abruptly when Hope visits him in California. She so desperately wants the perfect boyfriend that she’s willing to shut out all evidence to the contrary and minimises Jamie’s narcissistic behaviour. It’s extremely powerful and not, perhaps, what people will expect from Smale. "It’s a delicate topic to write about for this age group but I think it’s so important. Sometimes it’s easy to stay in relationships that are making us unhappy or are dangerous or unhealthy or toxic. Girls need to know when to walk away."

Feminism or, as Smale puts it, "kicking the ass of patriarchy", is central to her outlook as a writer. She sees her protagonists as taking on a predominantly male literary canon that has positioned girls "as passive, as pretty, as silent". Stories, Smale believes, are key in changing that message. "The books children read are how they first learn how the world is and what it can be. Girls need stories that empower them, and fire them up and give them hope."

If Geek Girl was about updating fairytales with a heroine who actually gets to take control and have adventures, then Happy Girl Lucky, Smale realised, is her response to Tennyson’s "The Lady of Shallott". Her mother—"who doesn’t believe in age-appropriate reading"—read the poem to her as a small child and Smale recalls it as beautiful but infuriating. "It seemed incredibly unequal that Elaine quietly died for love, while Lancelot casually judged the hotness of her lifeless body, or that this imbalance was considered even slightly romantic."

Hope’s story is that of a contemporary Elaine, a lonely girl, shut off from the world and looking to love for escape. "I could give her not only a voice this time, but agency." Instead of love and beauty as the pinnacle of the female experience, Smale replaced "it with freedom, independence and strength."

It’s credit to Smale’s writing that the book feels pitch-perfect for her young teen audience despite some darker themes, much of this due to her use of humour to bring balance and warmth. Comedy, she believes, "brings books to life. Once you’ve made someone laugh you can make them cry. You can handle more complicated issues if you present it with humour." She clearly feels a real connection with her readers and speaks about her audience with such passion that it’s hard to imagine her writing for any other age group.

At school events, writing classes, in cafés, she finds herself constantly "listening and watching for what it is teenagers want, what it is that excites them, what it is they’re struggling with". She feels like a big sister to her readers, which is mirrored in her warm, wise and inspirational tone. "They’re an incredibly rewarding age group to write for. The books you love at that age stay with you forever, there’s something so special about that, and I feel really privileged to be able to write for them."