You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

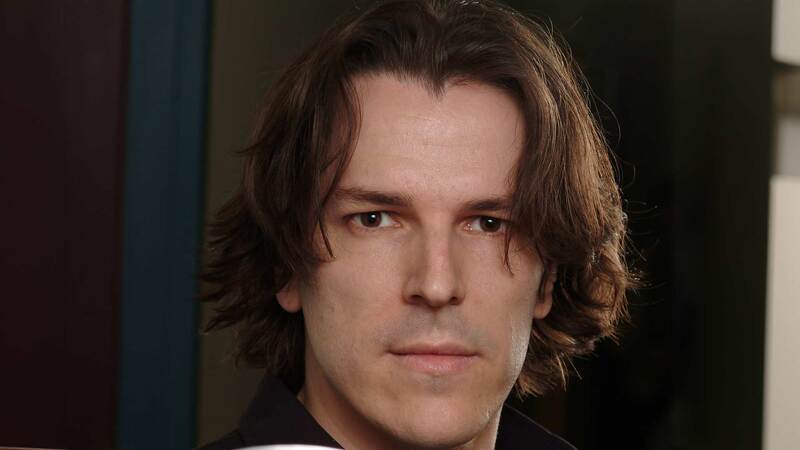

Piers Torday | 'Reading, writing, telling and sharing stories are the building blocks of humanity and civilisation'

Last spring Piers Torday retreated "from the chaos of Brexit and Trump" into a world of nostalgia and back to the book that, he says, "opened my eyes to the potential of storytelling". One of the most memorable books of his childhood, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was, he tells me over the telephone from his London home, "the first time I really understood that reading was a magical act". As a child he "hadn’t a clue" that the story was a Christian allegory. "It’s a book of its time and I’m definitely not going to be a cheerleader for C S Lewis."

But that magic of stepping through the wardrobe is what hooked him. "The appeal for me was the imagination and the world that I loved coming back to. I read the whole series and began to understand that fantasy worlds could be places to escape to." Lewis was writing at the end of the Second World War, the beginning of an age Torday feels is now coming to an end with Brexit. "I was trying to write a book to make sense of where we were, partly for myself and partly for children of today. I wanted to write about those feelings, that sense of some connection with the past that we once had that is being reshaped."

The idea began to evolve. What if the children who tumbled through a wardrobe in 1940s England discovered not a Christian allegorical fantasy but a more modern struggle? "The idea of using a classic fantasy text that everyone recognises but to then start using some more contemporary issues once we got inside was really the hook." His first challenge was to strike the right balance between homage and creating something very original. He initially planned to write a shorter story close in length to the originals: The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe is a modest 36,000 words long. But in the age of Rowling and Netflix he feels "children want more texture, more layer and detail than I think you get in the originals". He worked hard to evoke the atmosphere, pace and warmth of the Narnia stories, using "the plot of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe as a handrail", with enough nostalgic nods to satisfy readers while creating his own unique story.

The result is one of the most clever and ambitious children’s books of the year. The Lost Magician begins with four children sent away from the war in London to the country house of Professor Diana Kelly, a scientist at military research facility Porton Down. There, a magic door leads the children into a library and the world of Folio, an enchanted kingdom of fairy knights, bears and tree gods under threat from The Unreads, a sinister robot army. Opposing factions are locked in eternal war and the children’s only hope is to find their creator, a magician who has been lost for centuries. The narrative is framed by papers from the National Security Archives telling of a shady government venture to investigate The Magician Project.

The characters of the children are similar in tone to the Pevensies (from The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe) but have more flesh, depth and nuance here. "I wanted to play with the genders," Torday tells me, giving Larry, a very sensitive little boy, the role of discovering the door. The Edmund character, Evie, is particularly interesting. In the Narnia stories Edmund is painted as the treacherous one, but here Evie’s decisions are borne "not out of any sense of disloyalty but because she felt the need to act for change, which is so important in our own time". And because the book is so much about stories and reading, Torday felt it "important to have someone for whom reading wasn’t so easy," creating a dyslexic character in Simon.

In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe the Second World War is little more than a footnote but Torday’s children are deeply traumatised by their experiences. Writing so soon after the war "the last thing C S Lewis wanted to mention was the actual war. People wanted escapism and comforting". Writing from a modern perspective gave Torday an opportunity to counterbalance the nostalgia. "It wasn’t all golden summers and lashings of ginger ale." The idea of recovery from war is central.

The book is very much Torday’s love letter to reading, imagination and libraries. In a playful echo of Narnia’s Professor Kirke, a Torday character asks "What do they teach you in your schools?" "Grammar, mainly," is the morose response and an issue Torday is passionate about. "Reading, writing, telling and sharing stories are the building blocks of humanity and civilisation. They are created by the imagination and to reduce reading in schools to a set of data and metrics is, I think, so misguided." Reading, he believes, is about "wonder and joy and pleasure and freedom and risk and exploration" and he sees libraries with their capacity for children "to roam free and make unsupervised choices that could lead to discovery" as central to this. He fears that critical thinking skills are at risk and that knowledge is in danger of becoming piecemeal and knee-deep. "You’re potentially creating a society which is less connected and less harmonious," he says, where people may share the views of his White Witch character Jana who observes that, "A little wonder is a dangerous thing."

Torday grew up in Northumberland. His father worked for the family engineering business and his mother ran a children’s bookshop in Hexham. Visitors to the shop included Roald Dahl and Eva Ibbotson and his early years were surrounded by books. Torday initially looked to his childhood loves of theatre and TV as career options. "Essentially I’ve tried to spend my life doing things I enjoyed as a child," he laughs. Working in production and writing for TV proved to be invaluable experience. "You have to write a lot, you have to boil ideas down to their essence and you have to pitch ideas, discuss ideas and fight for your idea endlessly." But it was only when his father Paul Torday published his own début, Salmon Fishing in the Yemen, in 2007 that Piers began to see writing as a serious option. An idea for a big family drama about animals had got nowhere on TV so he enrolled on a creative writing course with Arvon and wrote it as a book. His début The Last Wild was published to wide acclaim in 2013 and the trilogy went on to win the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize.

Quercus has bought three books in The Lost Magician series; the first has a beautifully escapist cover illustration by Ben Mantle. The second book is set in 1984 and will star the children of The Lost Magician’s protagonists while a third book is set in the future. The government research framing device will provide the series story arc: who is the lost magician and why has he created this world?

Torday may use a traditional fantasy plot but the contrast between the nostalgia and the futuristic elements of his Unreads feels fiercely original and will develop over the course of the series. As we move into a future ever more reliant on data, artificial intelligence and automation, exploring this element was vital. “Children really do want a book that connects with the modern world they live in.”

Extract

It was a kind of manor house, of which there are many in that part of the world, and to the children it just looked very old and very smart. The stone was honey coloured, blazing in the afternoon sun, and there were roses clambering up the side. They twisted over windows so full of sunlight that the children couldn’t see into the house at all. It felt more like the house was looking out at them.

"Welcome to Barfield Hall," said Professor Kelly, applying the brake expertly, which made a satisfying hiss. "Very old, even older than me. Also comes with the job."

The children made faces at each other. They didn’t know what the Professor’s job was. All they knew was they were to stay here for the summer while their mother searched for a new home in London. The Professor was a friend of her mother, although the exact nature of that connection was shrouded in mystery.

"Mrs Martin, the housekeeper, will serve you some tea in the drawing room at four," called out the Professor, already disappearing through the open front door. "Feel free to explore, but the top floor is out of bounds. It’s not . . ."

The rest of her words were lost as she melted into a shadowy corridor, and faded from view.