You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Richard Mabey | 'I get a bit pissed off at the idea that reconnecting with nature is a kind of Prozac'

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

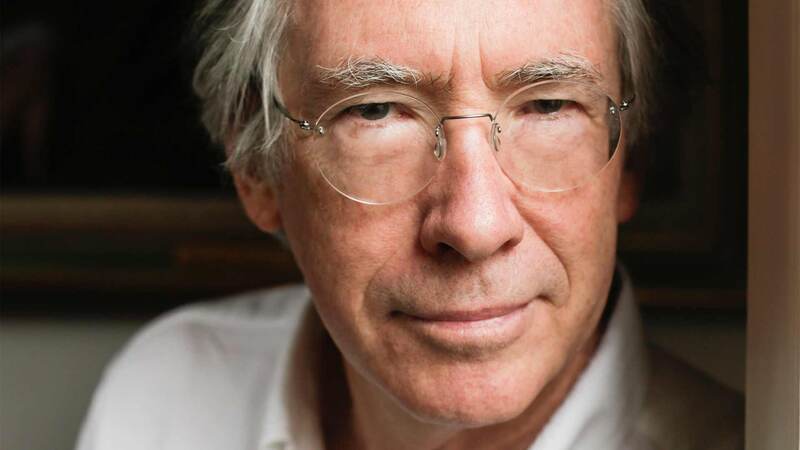

“Plants are not thought to be sexy. But there’s no reason why we shouldn’t both be entertained by them, and take on board the serious fact that something as seemingly passive and static as a plant can have remarkable abilities.” Richard Mabey is talking about his forthcoming book, The Cabaret of Plants: Botany and the Imagination, a varied, vigorous, cross-pollinating look at plant species that have fertilised our imaginations, awoken our sense of wonder and overturned our human thinking about what a plant is.

We are sitting outside Mabey’s thatched Norfolk farmhouse, which dates from the 16th century. A grapevine garlands the pergola above our heads; hollyhocks bow in the breeze and ripe elderberries keep catching my eye. Later we take a walk to see the pond (used in former times as a retting pool to soak hemp fibres for rope-making) and into a wilderness of ash trees and “mazzards”— the wild sweet cherry trees after which the house is named.

Mabey is one of our most distinguished writers on the natural world; the author of numerous acclaimed books, including a Whitbread Award-winning biography of naturalist Gilbert White; the glorious Flora Britannica, his groundbreaking cultural and botanical compendium; and most recently the delightful Dreams of the Good Life, his portrait of Flora Thompson, author of Lark Rise to Candleford.

Cabaret is his bid to rescue plants from being regarded merely as utilitarian and decorative objects. He reminds us of their theatricality, their sheer extravagance and their remarkable physical properties, which have inspired everything from Isaac Newton’s positing of gravity as a fundamental cosmic force (the apple that fell on his head was a scarce variety called Beauty of Kent, we learn); to the poetry of John Clare and the birth of Impressionist painting (this seductive idea is discussed in an enthralling chapter on ProvencÃßal olives).

And he’s wryly funny. His musings on Wordsworth’s famous daffodil poem produce the observation that “clouds in the Lake District are, on whole, very rarely lonely”. There is robust science here too, from an account of the discovery of photosynthesis, to the latest findings about plant “intelligence”. We can point to the ways in which plants permeate our daily lives, but only sometimes, says Mabey, do we glimpse what is important for the plant itself. Plants are vital, autonomous beings with “agendas of their own”, he tells us. And we should spend more time wondering at that.

Mabey cannot remember a time when he was not wondering at plants; from the feral childhood hours he spent eating hawthorn berries and discovering the best kinds of wood with which to build dens in the jungly wilderness which abutted the end of his garden; to his eagerness, aged 16, to trump his elder, clever-clogs sister and identify a mysterious orange-flowered plant she had spotted on one of her walks (Orange Balsam, or impatiens capensis, as he discovered from a flower book in W H Smith).

His early botanical enthusiasms crystallised a few years later when he started spending holidays with a gang of friends on the north Norfolk coast. “We discovered this amazing landscape: salt marshes from which the local people still pulled edible wild plants, a fact which seemed quite stunning to us and of a different order from eating blackberries and things like that. When I left university and was thinking seriously about writing, I had the idea that the atavistic tradition of gathering wild plants would make a sensational book. Collins took it at first bite. But it was appalled by the title Food for Free, which had come to me fully formed, as all good titles do. I knew it hit the right note for the times—the interest in ecology and food quality was just starting—but Collins thought it should be called The Edible Plants of Hedgerow Bottoms instead. I said: ‘the book comes away from you if you call it that.’“

A quarter of a million sales later, Collins sent him a letter of apology. Food for Free, first published in 1972, Mabey dubs his “postmodern guide to foraging”: has never been out of print since.

Marsh samphire, the “quirky sea vegetable” responsible for germinating this first book, was also an inspiration for Cabaret. “Samphire taught me that the divisions between plant as sustenance for the body and nourishment for the imagination, and between scientific fascination and Romantic inspiration were fluid,” he writes. His agent originally suggested he write A History of the World in 100 Plants—“’How quinine helped the white man to invade the tropics and kept the colonialists free of malaria’ sort of thing. Well that’s the aspect of plants I am least interested in,” Mabey says. “But the idea stayed with me and linked with what I am interested in, which is how plants impact on the human imagination.”

Despite often being lauded as the “father figure of modern nature writing in the UK”, Mabey’s genial countenance clouds at the term “nature writing”. “In a sense all writing is nature writing; there’s some terrific nature writing in Ian McEwan. The other 10 million species on the planet aren’t human, so they ought to permeate everything you do and think about. It would be a very disgraceful piece of fiction if at no point did the characters cross paths with other species.” While Mabey welcomes the recent flowering of so-called “new nature writing” and its broad church—admiring in particular the work of Kathleen Jamie, Tim Dee and the late Oliver Rackham—he professes some queasiness “when nature writing is not about nature at all but rather a route to an exploration of the self”.

I’m initially rather surprised by this statement. Mabey moved to Norfolk from his native Chilterns in 2002 during a crippling period of depression and describes that difficult time in his profound and starkly beautiful Nature Cure. But later, when I re-read bits of the book, I remembered that it is both pastorally uplifting and probably one of the least self-indulgent memoirs of depression ever written. Mabey rarely dwells on his illness, majoring instead on his explorations of the new landscape in his life. And in any case, he baulks at the notion that nature is always healing.

“I get a bit pissed off at the idea that reconnecting with nature is a kind of Prozac, which automatically generates unqualified happiness and wellbeing. It can be like that but equally if you properly reconnect with nature, if you go out there with your eyes and your soul open, you’ll find yourself in tears as often as not.”

However Mabey is also quick to eschew what he calls the “dreadful solemnity” of a lot of writing in his field: “I hope there’s quite a lot of funny stuff in Cabaret because I find the natural world immeasurably comic.” And indeed he invites us to become the audience for “an immense vegetal theatre in the round”, hoping to recapture the spirit of the late 18th and 19th centuries, when the Victorians went mad for ferns and rammed Kew Gardens to view the sensational blooms of Amazonian water lily Victoria amazonica; a time when plants were “just about the most interesting things on the planet”.

But perhaps the most important reason we should come to the Cabaret, he says, is that respecting the vitality of plants is the best way for us to coexist with them in these challenging times for our planet. “I hope we can respectfully maintain the independence of our kingdoms, not as irrevocably separate orders, but as two linked pathways to the challenges of being alive.”