You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

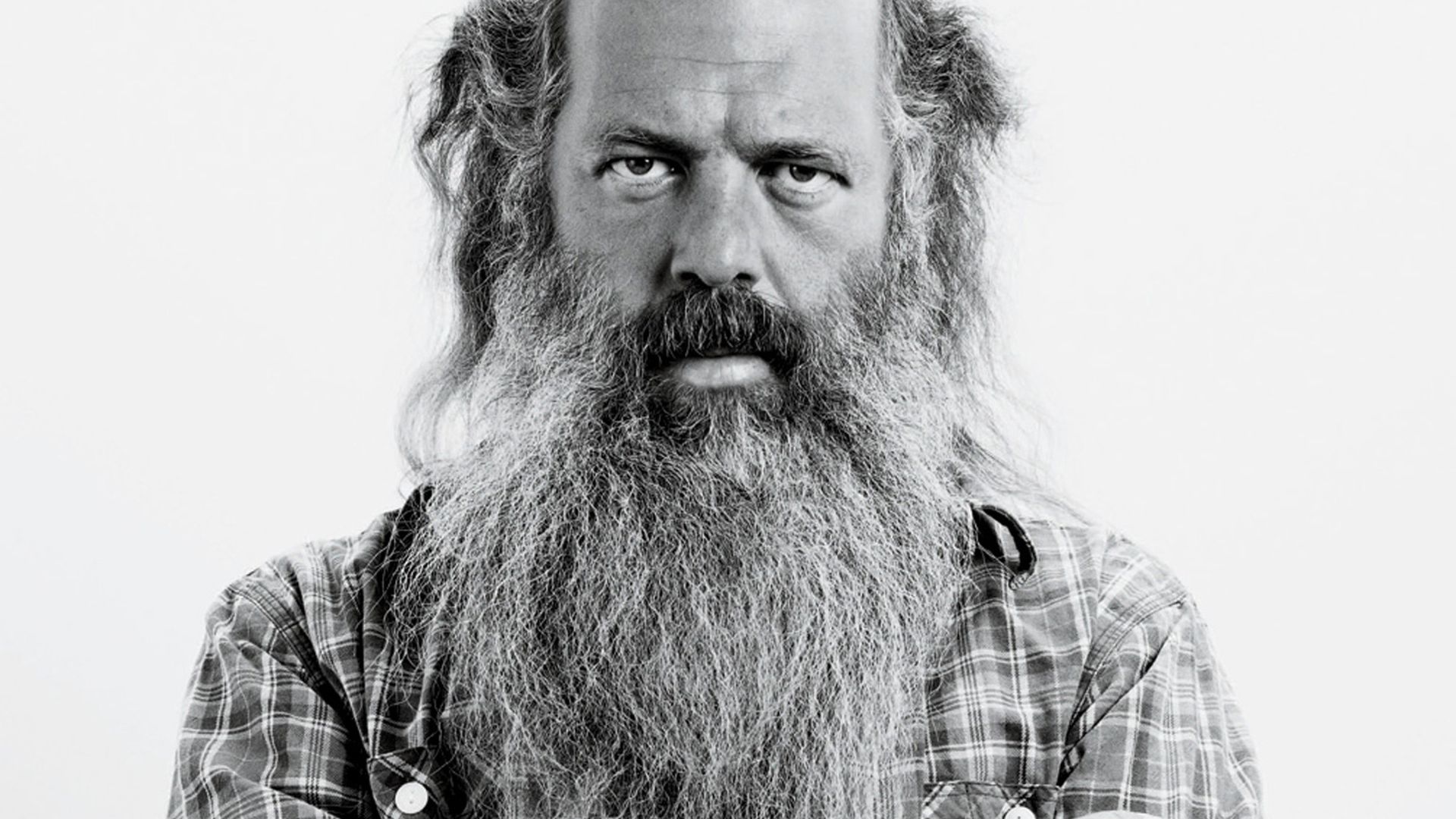

Rick Rubin in conversation about his life in music industry, inspiration and a call to creative action

Philip Jones

Philip JonesPhilip is editor of The Bookseller, a position he took up in August 2012. Before that he was deputy editor, having first joined the ...more

Music producer Rick Rubin has distilled a lifetime’s experience working in the studio into a book encouraging readers to graft in pursuit of creative excellence.

Philip is editor of The Bookseller, a position he took up in August 2012. Before that he was deputy editor, having first joined the ...more

Rick Rubin is two things. He is an American record producer, former co-president of Columbia Records and, it is said, one of the most influential of a generation, having worked with everyone from the Beastie Boys to the Red Hot Chili Peppers to Slayer to Adele. But outside of this sphere, he is relatively unknown. Google him and you’ll find a YouTube documentary, entitled: “The Invisibility of Hip Hop’s Greatest Producer”.

The latter might just change with the publication in January by Canongate of The Creative Act: A Way of Being, a sort of meditation, examination and explanation of why some shit works, why some doesn’t, and why it matters to keep trying. For those wanting the low-down on such characters as L L Cool J, Michael “Mike D” Diamond of the Beastie Boys or Adele, this is not that book. For those in search of a little inspiration, guidance and an occasional kick up the rump, this might be the tome.

And from the maestro too: when Rubin tells you “there’s a time for certain ideas to arrive”, you would do well to look up and take notice. In the flesh, Rubin is—as you might expect—urbane, laid-back, happy in the moment. Also interested. His arrival in the UK coincides with the death of the Queen. An American in London at a time of national upheaval. “It’s odd,” he says. Not wrong.

The book is a result of having spent 40 years around creative people, with the music producer attempting to figure out how the magic works. He is credited on such albums as “American Recordings” (Johnny Cash), “Californication” (Red Hot Chili Peppers) and “21” (Adele), so he has something of a backlist to consider. “In the moment, it’s always been intuitive. I never went to school to learn this. So I spent some time looking back in an attempt to reverse-engineer how it happened. Sometimes I couldn’t.”

We are trying to go in a direction and then something raises its hand, and we follow that thing

In a sense, Rubin is concerned with moments, and the wizardry that can sometimes arrive—or not. A pivot when something humdrum becomes spectacular, or a trigger when a project suddenly takes form. The problem: it’s somewhat indefinable and unpredictable, even if, as Rubin suggests, we know it when it occurs. “The thing where we usually say, ‘There it is’, is not the thing we often are aiming directly for. We are trying to go in a direction and then something raises its hand, and we follow that thing.”

This instinct about what is right is a thread woven through the book. Rubin offers few real-world examples in the text, but in conversation he cites a gig he attended where the US rock band Aerosmith was playing. “I saw them play 30 times and they were always amazing, and I saw one show later in their careers, and it wasn’t that great. I later found out that the bass player—I didn’t even understand how integral he was to the band—was sick, and they had a fill-in. He [the bass player] wasn’t one of the faces of the band, but it was like it evaporated.”

But you can’t force it. “I believe we luck into it when it happens,” he adds, “I’ve seen incredibly talented people have no success—and it’s not because they weren’t talented, it’s just that it’s not lining up—great bands, where all the members are great and they break up, and it never works like it did with the band.”

The end product

Rubin is also a do-er: he challenges creatives to get on with it and then get it out into the world. In his book, he draws a distinction between “experimenters” and “finishers”: one gets to the end point quickly, the other takes a more circuitous route. Both need to work together. The point for Rubin is to be in the game. He writes: “Epiphanies are hidden in the most ordinary of moments: the casting of a shadow, the smell of a match igniting, an unusual phrase overheard or misheard. A dedication to the practice of showing up on a regular basis is the main requirement.”

It’s not a conveyor belt: it has a time when it wants to be. It cannot be scheduled. If you are a slave to the schedule, it won’t be all it can be

As you would expect, the book had its own particular journey. Rubin says he had been working on different versions of the title for four years, never quite nailing it before now. “I worked with different people in the process and it was gruelling, to get it to feel the way I wanted it to feel. There was a version of the book three years ago; the content was similar but the feeling of it... it did not feel like a call to action. It was beautiful, but it wasn’t inspirational.” Rubin says the problem was that “it didn’t make me want to make anything”, which, he says, is the purpose of the book. “Jamie [Byng, c.e.o. and publisher of Canongate] was helpful. I said, ‘I don’t think it is the book, but any thoughts?’ He said, ‘No, but that’s not the book’.” Eventually, a pared-back version of that book came to fruition. “A lot of the records I produce are about stripping things away, and here I wanted to strip as much away as possible to get it as essential as it could be.”

I use the term pared-back with reservation. The title is still 400 pages, and decent heft. Canongate is to publish a cloth-bound edition of the book in January, with Rubin primed to embark on a media tour, kicking off with a spot on BBC Radio 4’s “Desert Island Discs”.

Of course, I ask how the music business compares to publishing—in the US he is working with Penguin Random House, in the UK it is Canongate, so he has a dual perspective. “The music business seems slightly more modern. Not much,” he says drily, remarking that albums today can be finished and delivered (via the web) pretty quickly, whereas finished books still take longer to distil. He frets that in both sectors, the schedule is the death of creativity. “It’s not a conveyor belt: it has a time when it wants to be. It cannot be scheduled. If you are a slave to the schedule, it won’t be all it can be.”

Extract

Those who do not engage in the traditional arts might be wary of calling themselves artists. They might perceive creativity as something extraordinary or beyond their capabilities. A calling for the special few who are born with these gifts.

Fortunately, this is not the case.

Creativity is not a rare ability. It is not difficult to access. Creativity is a fundamental aspect of being human. It’s our birthright. And it’s for all of us.

Creativity doesn’t exclusively relate to making art. We all engage in this act on a daily basis.

To create is to bring something into existence that wasn’t there before. It could be a conversation, the solution to a problem, a note to a friend, the rearrangement of furniture in a room, a new route home to avoid a traffic jam. What you make doesn’t have to be witnessed, recorded, sold, or encased in glass for it to be a work of art.

Finally, I ask how he will judge the book’s success? Does it need to be a hit? “I don’t care. I obviously want people to like it if it is useful. I wrote it to be of use. If it is of use, it has succeeded. If someone takes it and makes something beautiful, we win.”