You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Robert Dinsdale on morality, legends and imagination

Katie Fraser is the chair of the YA Book Prize and staff writer at The Bookseller. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International ...more

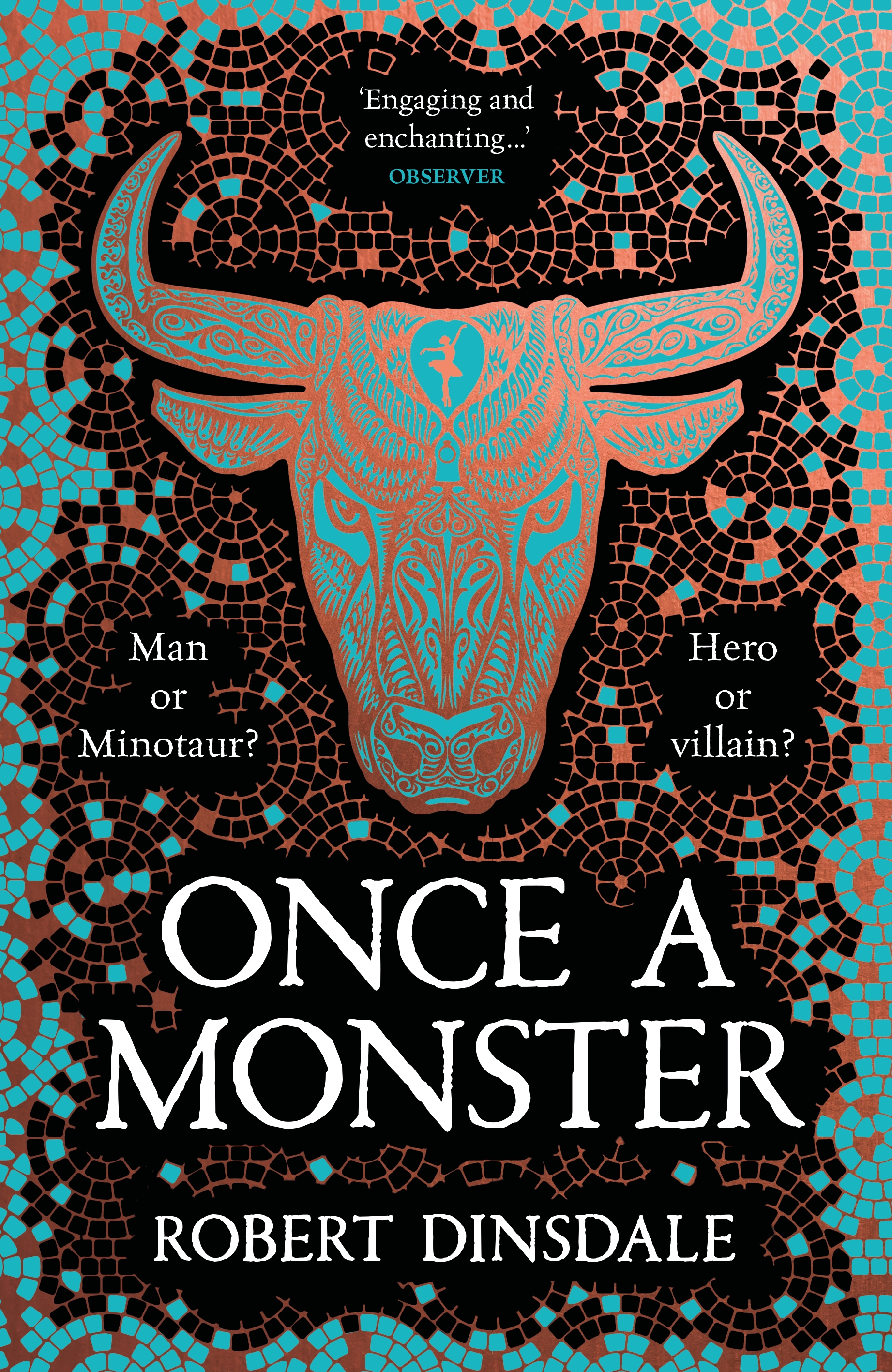

Relocating the Minotaur legend to Victorian London, Robert Dinsdale‘s latest novel explores modern morality, agency and the line between good and evil.

Katie Fraser is the chair of the YA Book Prize and staff writer at The Bookseller. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International ...more

The most interesting stories to me have always been [about] good and evil inside a person”, says Robert Dinsdale over Zoom from his book-filled living room in Leigh-on-Sea. “That’s basically what the Minotaur represented to me, the push and pull of good and evil inside a person.”

Ancient Greek retellings, especially from a feminist perspective, have become a mainstay in the publishing industry in recent years, often set contemporaneously to take the original text to task for overlooking female characters or non-heterosexual relationships. But Robert Dinsdale’s Once a Monster offers something different, taking the Minotaur legend out of Ancient Greece and placing it in Victorian London to examine the meaning of humanity, morality and redemption.

The original Minotaur myth—where the half-bull, half-man creature is placed in a Labyrinth designed by master architect Daedalus, receiving the offering of human sacrifices before being killed by Theseus—stays in place, but with a small twist: the Minotaur survives. Wandering through time and history, the Minotaur adopts his stepfather’s name (Minos), and we meet him in smog-filled Victorian London, washed up on the riverside and left for dead. He is found by Nell, a small girl who dreams of ballet, and a group of mudlarks who comb the River Thames looking for treasure to earn their keep with the tyrannical Mr Murdstone, a Fagan-like figure desperate to climb the social ladder. It is through Nell, and her shining kindness, that the reader perceives Minos, a beast to all others except for her, and their friendship will change the course of his life.

It is not about being naturally evil or naturally good; it is about incrementally choosing which way you are going

It is an enchanting Dickensian tale blended with Ancient Greek myth where, in the space of a few lines, the narrative glides from the dirty riverbank and dark alleys of London to the depths of legend, the Labyrinth and figures of myth.

At the centre is a question, a decision to be made: the characters must choose between good and evil. “It is not about being naturally evil or naturally good; it is about incrementally choosing which way you are going”. Minos strives for betterment, a choice physically manifested in his appearance as his humanity is marked by a shift from bull to man: “Just because he was born with horns does not mean he has to wear the horns.”

A godless tale

But Minos is beleaguered by Murdstone who wants to sell him as a circus act and thus return to the wealth and status he once enjoyed. But who is the real monster? Minos may outwardly appear the monster, but he actively moves toward goodness in counterpoint to Murdstone’s conniving manipulations. There are no gods and goddesses in this tale to meddle in events; every action is a choice which Dinsdale attributes to the ability to “take charge of ourselves and make our own decisions”. What Minos learns is that, without deities to interfere, it is up to him: “He is learning that he’s got agency”.

There is a lesson in every legend and, for Dinsdale, the truth in his version of the Minotaur myth is that “we are all good and we are bad and nobody is purely one thing or another. We have all got the capacity to do good and we have all got the capacity to do horrible things too”. The decision is left to the individual as to which rules—the beast or the man.

As a figure of legend, Minos is a nexus of storytelling, of those stories told about him, to him and which he tells himself. The question of whether he will reckon with his blood-spattered past looms over the novel and the larger concern of whether it will consume him, transforming him back to a nightmare of the dark, is charged with resonance. “He has to change his story,” says Dinsdale, “and that is what the book is doing, changing the story.”

The force of change in Minos’ story is Nell. Having lived for thousands of years, Minos is the embodiment of history, memory and storytelling, but also becomes, perhaps most importantly, the witness to the story of Nell’s life. Nell cares for Minos when she finds him feverish and unconscious, seeing in him the capacity for goodness, a gentle giant rather than a monstrous being. “Small acts ripple,” Dinsdale says, and Nell’s actions are a case in point. Where Nell sees vulnerability and kindness, Murdstone and his cronies are led by atavism, seeing only opportunity and capital gain. She becomes Minos’ harbour, his light which guides him again and again to goodness, compassion and love.

Everything started with one image and this, for me, was a little girl sitting with a Minotaur, and I have had that image in my head for a long, long time

I ask Dinsdale if he ever considered having Minos discovered by an adult character, but in that version of the tale a “chaste love story didn’t work as well”. Unlike in adults, “you can see in kids their willingness to see good in everything and I think we get socially conditioned out of it somehow as you grow up”.

The weight age exerts on imagination is not a new concern for Dinsdale, having also informed his previous novel The Toymakers, set in a toyshop in the heart of Mayfair before and after the First World War: “In the first half of the book, everything is light and beautiful, because we are in this toyshop where this magical stuff manifests, and then the First World War comes along which is the book saying: ‘Everyone has got to grow up now’.”

Magic and realism

Dinsdale melds magic and reality in his storytelling. “I’m interested in how you look at real stuff through a fantastic lens” he says—using something “unreal” to “point at some other truth”. His ideas and homage to the speculative can be traced back to his childhood, to a time where imagination was fertile ground. Speaking on his inspiration for Once a Monster, he explains: “Everything started with one image and this, for me, was a little girl sitting with a Minotaur, and I have had that image in my head for a long, long time. I think almost everything I write now, and will write, is something that I invented when I was 13 or 14.” Dinsdale later added: “You don’t get that [childhood] back and that is why I say that I think every thing—every good idea I’ve got—is something that entered my head 25 years ago when the imagination was still so flexible, so willing to leap into something.”

Writing a children’s book is Dinsdale’s “principle ambition,” but he is at present unsure what his next project will be. “I always assume that every book is my last one. I think because the first books I published didn’t sell anything, I felt like people [didn’t] know that I existed as a writer, so I just go with that mentality of ‘every next book is another last book’.” However, ideas are percolating, and Dinsdale is “sure they will be based on the images that I have got in my head”.