You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Robin Stevens discusses the close of her successful series Murder Most Unladylike

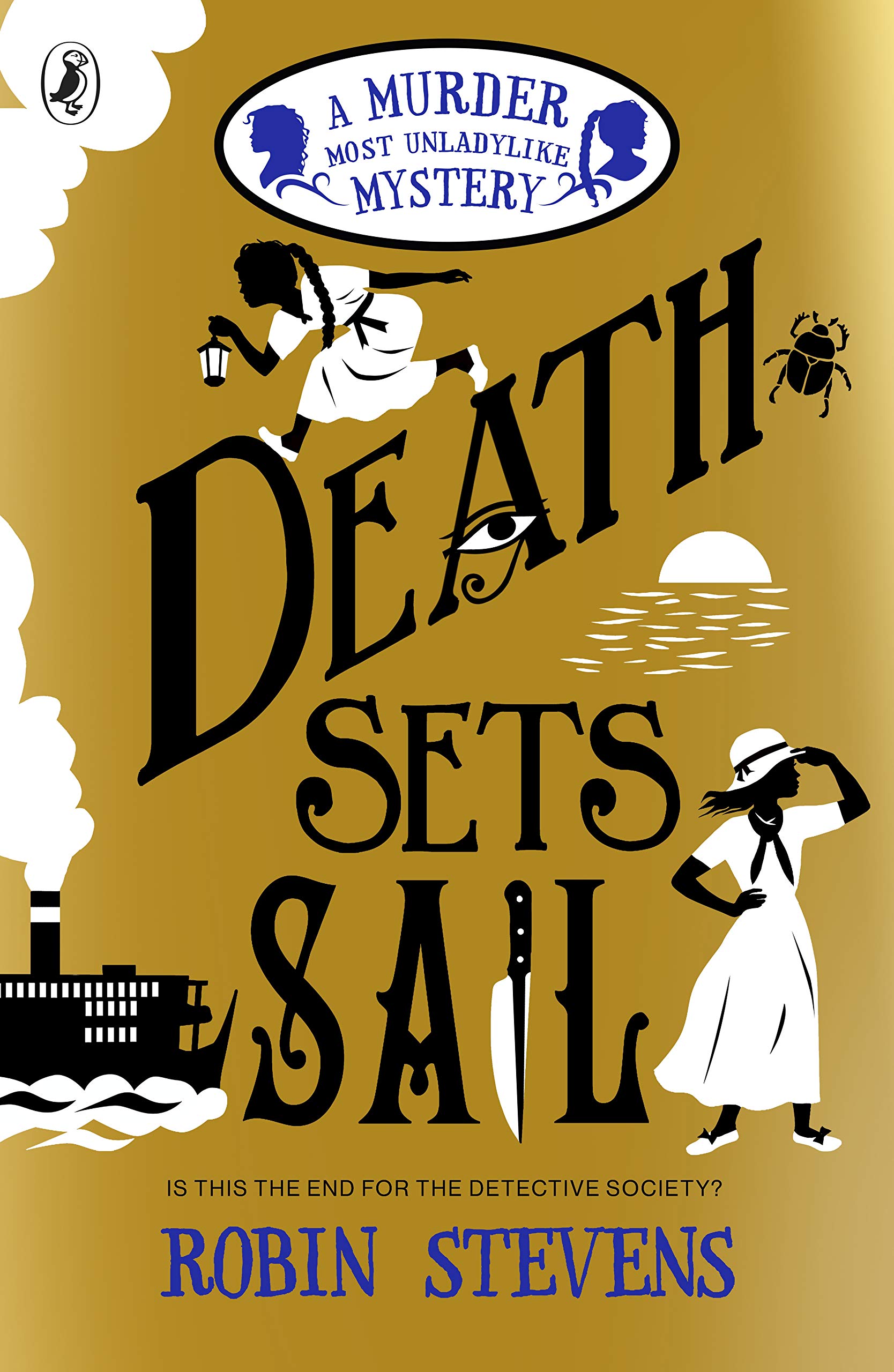

Award-winning Robin Stevens reflects on closing her Murder Most Unladylike series with its ninth adventure

In 2010, Robin Stevens was an aspiring writer with an idea for “a murder in a boarding school with two girl detectives”. Ten years on, the Murder Most Unladylike series has won awards, sold close to 725,000 copies in the UK and enjoys a devoted fanbase. In August, Puffin will publish Death Sets Sail, the ninth and final novel. So, I ask, why choose to end such a successful series? “It was a really big decision,” Stevens tells me, speaking from her Oxford home.

Heroines Hazel Wong and Daisy Wells are 13 in the first book, and on the cusp of turning 16 in the ninth, very much teenagers. ‘The gap between who you are when you’re 13 and who you are when you’re 15 is huge. The suspects are not looking at them as little girls any more, they are young women. It’s harder for them to get away with their schtick.” There is a poignant moment when the girls realise they can no longer hide under tables in pursuit of evidence, a tactic so successfully employed in the first title, First Class Murder.

I was really interested in female power, how women are trying to control the world around them

Stevens also had her readers firmly in mind. “It felt harder to write about a 15- or 16-year-old in a way that an eight-year-old would really care about. They’re falling in love, they’re having their first kisses. They’re moving towards YA.” The process, she admits, has been emotional. “Writing it, I was a mess! It’s been 10 years of my life. They have been in my head every day, but it feels like the right moment to move on.”

All aboard

Death Sets Sail sees Hazel and Daisy on a Nile cruise with classmate Amina, boy detectives The Junior Pinkertons, and Hazel’s father and sisters. Also aboard the SS Hatshepsut are The Breath of Life, a strange cult of genteel English ladies and gentlemen who believe themselves to be reincarnations of the ancient pharaohs. Their pursuit of ancient temples and mummies becomes something altogether more deadly when the leader of the cult is found dead in her cabin. The Breath of Life is loosely based on real-life cults like the Panacea Society, a 1920s group of women who believed they were disciples of God. Stevens was intrigued by this idea of a woman who thinks she is divine. “I was really interested in female power, how women are trying to control the world around them… I thought it was an interesting thing to have a female-led cult going up against a female detective society of young women trying to work out their place in the world.” Billed as their deadliest adventure yet, the blurb teases that only one of the Detective Society will make it home alive. Stevens’ fans are losing it, she confesses. “I’m getting emails every day. I feel so guilty, but I think it’s more exciting this way. The tension is high.”

I really remember that was a time of life when I was working out who I was, who my friends were, how I wanted to be seen in the world

The book fulfils Stevens’ longstanding fascination with Egypt and is in part a homage to Agatha Christie; the section titles are all titles of Christie books. She calls Death on the Nile “one of the foundational texts”, and has long adored “the glamour, the setting, the incredible temples and boats” of both the book and its 1970s film adaptation. Stevens visited Egypt as a teenager but a trip during editing provided vital inspiration. “I’m definitely someone who needs to understand the setting of the books. I need to be able to walk through it, like a movie set in my mind. The first draft was lacking, but after my visit to Egypt everything snapped into place.”

Stevens has always been keen that each book should stand alone, in the style of Poirot or Miss Marple, with no particular series arc. While the expert plotting and the boarding school-murder mash-up attracted initial attention, the development of the girls’ characters and the evolution of their friendship has proved just as important to the lasting popularity of the series. Like Hazel and Daisy, Stevens went to boarding school and made incredibly strong friendships. “That’s what I wanted to write about. I really remember that was a time of life when I was working out who I was, who my friends were, how I wanted to be seen in the world.”

My generation missed out on any book like that. I want to help kids of this generation feel comfortable with who they are

In the first book, Chinese new girl Hazel is an outsider at Deepdean School, “very shy, very awkward”. The

Hazel we encounter in Death Sets Sail is quite different. “I wanted, as the books have gone on, to show her as the star of the series, to give her confidence and show her growing up.” Daisy, by contrast, “starts off thinking she’s quite brilliant”, but over the course of the series she learns to listen to Hazel and to accept other points of view. It is a more vulnerable Daisy we meet in book nine. “Showing her having a crush and falling in love, I got to show her being uncertain.”

A level playing field

Both Hazel and Daisy have had crushes in earlier books but in Death Sets Sail the romance is heightened, and both girls experience their first kisses. Daisy came out in Death in the Spotlight and Stevens has been overwhelmed by the response from her readers. “I still, almost every day, get letters saying, ‘This is amazing, I can see myself in Daisy.’” Queer protagonists remain a rare thing in middle-grade fiction. “My generation missed out on any book like that. I want to help kids of this generation feel comfortable with who they are.” She has been careful to portray the girls’ experiences as being of equal importance and of equal maturity, pointing to “an incorrect sense in [the] media” that queer romance is more mature than straight romance and that children’s books are not a place for LGBT+ characters. “I think that is deep-rooted and comes in part from laws like Section 28. It gave everyone the idea it was forbidden or dangerous, when of course it was just people falling in love with each other. The shadow is still there. I wanted to show it really is the same.” Although, she laughs, Daisy doesn’t think it’s the same at all: “Daisy thinks her crushes are way better than Hazel’s!”

Murder Most Unladylike has been groundbreaking in the diversity of its two leads. Growing up, Stevens realised there was a huge gap between the characters in the traditional school stories she loved and people in her own school, where many of her friends were from Hong Kong. “I couldn’t understand why school stories were so white, when the reality of being at school is that there are people from all different backgrounds.” She is passionate about the drive for greater inclusivity in publishing. “I am really proud to have Hazel as one of the main characters in my books, but I really want to be part of a push for diversity in [terms of the] authors of children’s books, so kids can read about kids like them, by authors like them,” highlighting Sharna Jackson’s High Rise Mystery and Serena Patel’s Anisha, Accidental Detective as ones to watch. “The world is much more diverse than most books acknowledge, but there is so much more work to do on all fronts.”