You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

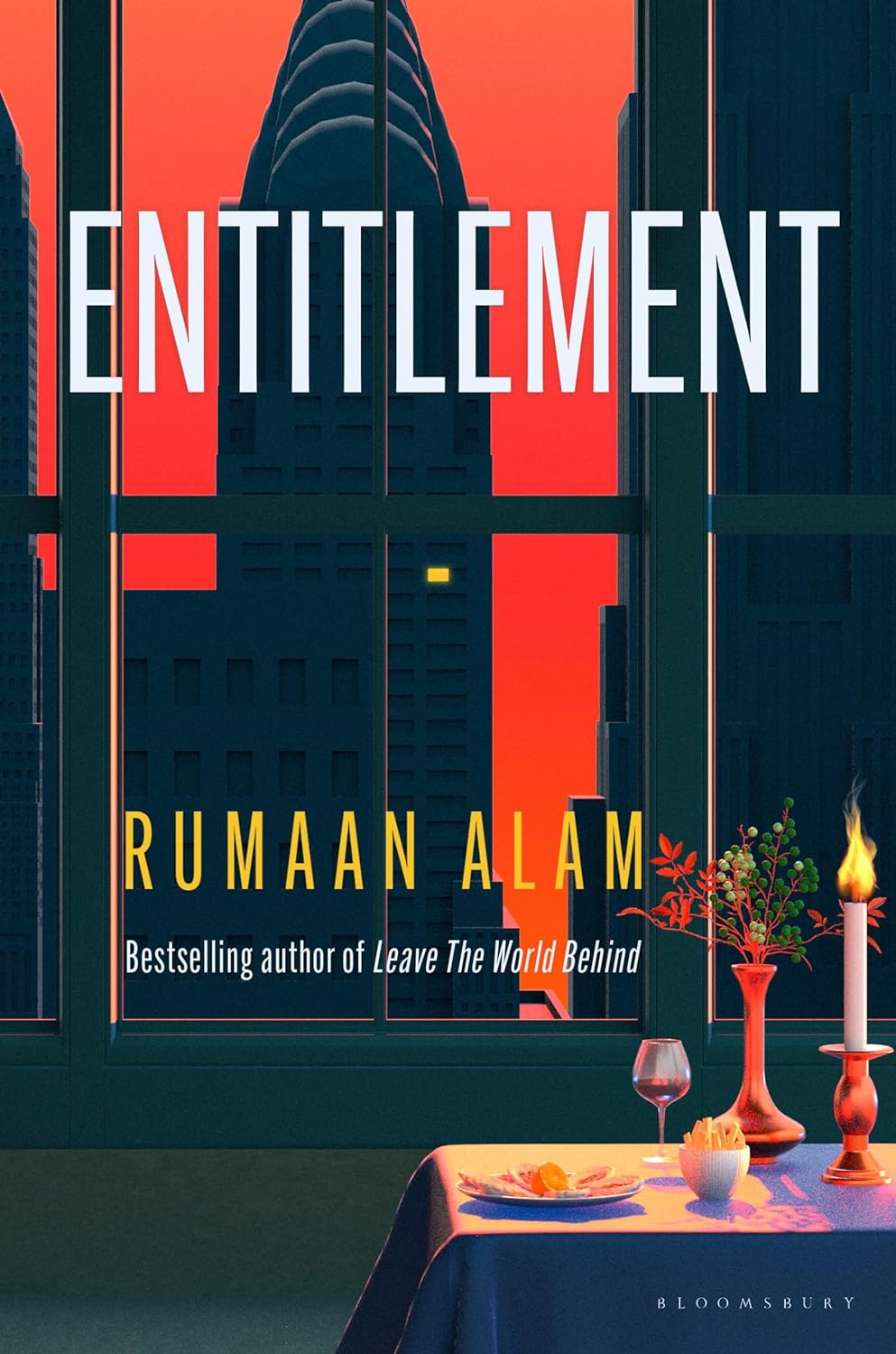

Rumaan Alam explores race, family and complex power dynamics in his timely fourth novel

Madeleine Feeny is a book critic published in the New York Times, Guardian, Financial Times and Telegraph, among others, and the fiction ...more

Rumaan Alam explores race, family and complex power dynamics in his timely fourth novel.

Madeleine Feeny is a book critic published in the New York Times, Guardian, Financial Times and Telegraph, among others, and the fiction ...more

Money has replaced faith as the guiding principle of contemporary life. It is the force that essentially drives everything,” says Rumaan Alam, the American author of the hit novel Leave the World Behind, his third novel, but his first to be published in the UK. It was a finalist for the National Book Award and the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction, selected as a Waterstones Fiction Book of the Month and a Barack Obama Summer Reading pick, and made into a film starring Julia Roberts. His fourth novel, Entitlement, is an elegant, disorienting drama about financial anxiety in middle-class New York, hinging on the charged relationship between a young Black woman, Brooke Orr, and her octogenarian white billionaire boss, Asher Jaffee. Animated by the same panic that fuelled its predecessor, albeit with a different catalyst, Entitlement likewise explores family, parenthood and race in a bourgeois milieu, infusing a tense narrative with sly humour.

Although this is a book about money, it resists simply bludgeoning the rich, unpicking instead the complexities of philanthropy and privilege, and notions of what we owe and deserve. It speaks to a cultural moment in which traditional markers of adulthood—job security, homeownership and family life—are increasingly unattainable for young people, many of whom feel let down by the promises of education, aspiration and professional fulfilment. Alongside this middle-class reality, the luxurious lives of a growing cohort of super-rich are increasingly visible on social media and reality television.

It is 2014 and Brooke, disillusioned by teaching, has recently started working at Asher’s charitable foundation, founded in the wake of his daughter’s death, aged just 38. Having accrued his wealth through the endearingly wholesome sale of office supplies, with the slogan: “Jaffee... In a Jiffy!”, and the timely purchase of real estate, Asher subverts the post-#MeToo caricature of a powerful older man. Neither bigot nor sexual predator, he is the “genial rich guy” very much “woven into American culture”.

Aged 33, Brooke is feeling the pressure to achieve, especially when she overhears her mother slating her new job. A reproductive health advocate, Maggie Orr capitalised on the new liberties feminism afforded her generation, adopting Brooke and her younger brother Alex, and raising them collectively in a quartet of women friends.

Brooke feels isolated in her family, by virtue of her race—both Maggie and Alex are white—but that’s not the determining factor, says Alam, over video call from New York, “because there are, of course, many well-adjusted people of one race being raised by parents of another race”. (With his husband, he parents two boys who are not the same race as him, a dynamic he explored in his second novel That Kind of Mother.) It does not help that Alex is engaged and has a rewarding job as an architect. Brooke doesn’t feel the same urge to settle down, so pins everything on work. When Asher selects her as his protégé, what was simply an escape route from teaching becomes an all-consuming vocation that leads her down a perilous path of desire and expectation. The finely balanced power dynamics sustain the tension. The reader is on high alert for exploitation, but although possessed of the unconscious magnetism of the hyper-successful, Asher is not actively manipulative. Each fulfils a role for the other: Asher is grieving a daughter, Brooke has no father figure. Each is beguiled by the other’s differences and flattered by their attention. It becomes a “strange kind of romance”, without the romance.

The currency that governs reading is time, not money... It is one of the last provinces of the sacred in contemporary life

Through Brooke’s attempts to foist a charitable donation on a children’s dance school, the novel explores the ethics of philanthropy: the self-interested motivations, the unforeseen consequences, the fact that some things exist outside the realm of money. This feels especially relevant following the Fossil Free Books literary festival controversy and the Sackler family “art-washing” scandal. “What was generosity and what was selfishness?” wonders Brooke. “Money didn’t matter to someone so rich.” Alam believes the only rational response to money’s “outsized” significance is a kind of insanity, “and if you think about it too much, you start to go a little crazy”. Accordingly, the novel tilts incrementally away from realism as it approaches its climax. Here Alam cites the influence of Tessa Hadley, “a writer who works in a very realist mode, and then tiptoes ever so slightly away”. (Other favourites include Saul Bellow, Anita Brookner and Don DeLillo, to whom he has been compared.) Alam likes to allow space for readerly interpretation, relishing the inscrutable edges of his characters. “Even the people you make up are mysterious.”

Although the third-person perspective mostly stays close to Brooke, it sometimes flits between characters, including Asher. This prominent male viewpoint is unusual for Alam, whose first two novels both put women centre stage. As a gay man, his close friendships are usually with women, and he has always felt more drawn to the rendering of the female psyche on the page. To challenge himself, he is currently writing a post-9/11 comedy starring two men. Like Brooke encountering Asher’s charisma, Alam was exposed to the heady forcefield of the rich and famous during the filming of Leave the World Behind. The success of that book has allowed him to write full time, “a huge gift”, yet his feet have been kept on the ground by parenthood. He enjoys discussing its influence because men are rarely asked about it and “there is a pretty glib, blanket idea that parenthood is the enemy of creativity, which has not been my experience”. Entitlement like his previous novel, confronts the dark side of being a parent, the life-changing awareness that “the chasm is right there, one accident away”.

While Alam exorcises some of this anxiety by writing fiction, having children also stops him obsessing over work. It offers hallowed moments, too, such as watching his son dance as a jellyfish in the school performance that inspired the novel’s. To Alam, reading occupies a similar space. “The currency that governs reading is time, not money, and booksellers and librarians know this. It is one of the last provinces of the sacred in contemporary life.”