You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Saara El-Arifi speaks about her debut fantasy trilogy

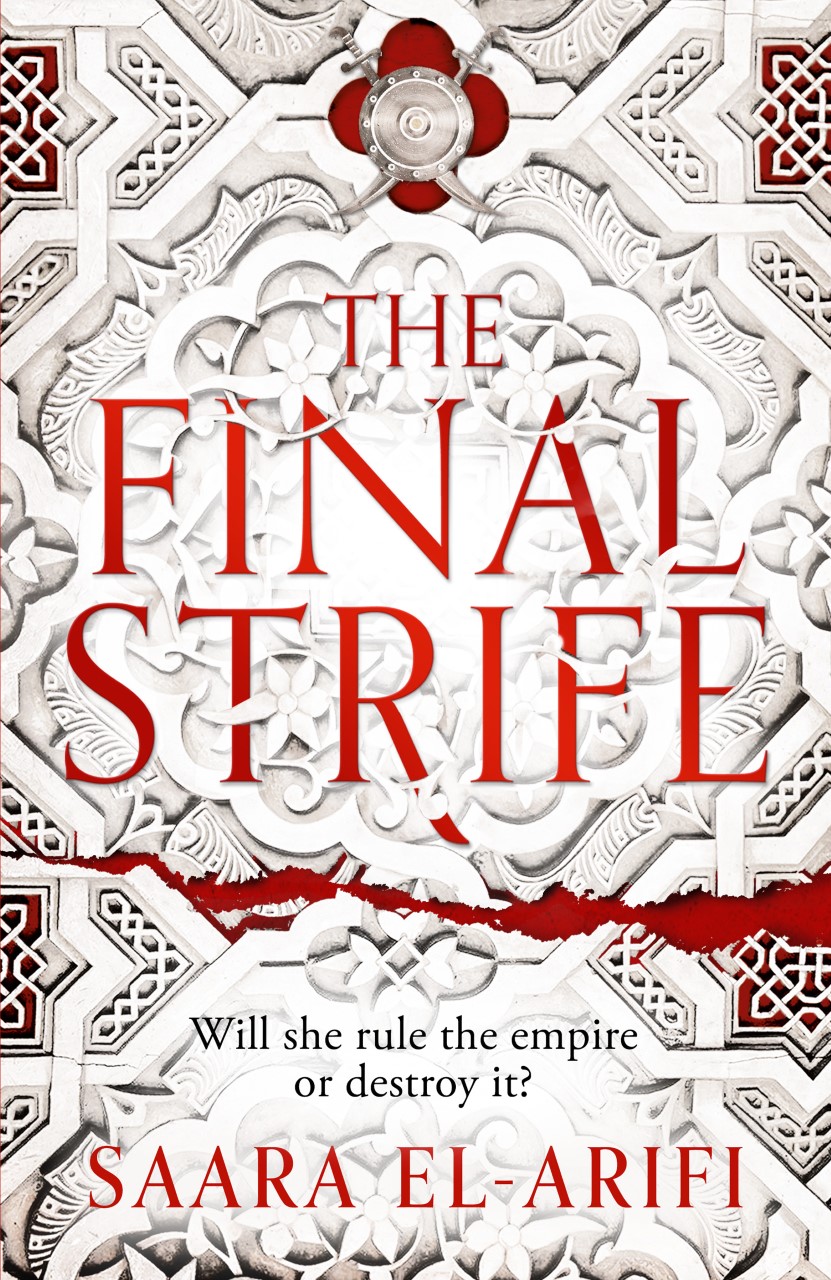

Debut author Saara El-Arifi speaks on her first novel The Final Strife – the first instalment in a wild new fantasy trilogy. Journalist Almaz Ohene, who lived in the same small northern town as El-Arifi, profiles her.

Saara El-Arifi’s heritage is intrinsically linked to the themes she explores in her writing. She was raised in the Middle East until her formative years, when her family swapped the Abu Dhabi desert for the English Peak District hills. This change of climate had a significant impact on her growth – not physically, she’s nearly 6ft tall – and she leaned what it means to be Black in a white world.

El-Arifi and I spent our late childhood and teens growing up together in a small northern English town (which was exceptionally white) as both of our families had settled there from abroad. Additionally, our mothers grew up together in Accra, Ghana in the 1950s and 1960s, which means that, up to a point, we have a unique shared history.

The two of us haven’t seen each other for a number of years and so when we see each other’s faces on our video call we’re excited. El-Arifi peers hard into her screen to get a better look at my surroundings.

“Ah the room!” El-Arifi exclaims.

I’m doing the interview from my childhood bedroom, where during our tween- and teen-hood, we’d play games like Monopoly, Cluedo and Dream Phone (for those who might not have heard of Dream Phone, the game came with a large pink phone and the object of the game was to find out which boy had a crush on you by dialling numbers and "talking" to the boys in order to gather clues.)

It was there that I discovered the genre of fantasy. It was such an escape

“It’s so special that the two of us are talking about our craft,” El-Arifi continues.

“Yes! Especially since we’ve both now matured into ‘the writer of the family’. How do you feel about this town now?”

“I struggle to go back there because apart from all of the miserable memories from that time” – El-Arifi lost her Dad, and supported both her younger sister and mother through cancers during the aughts – "I also see the sad and depressed girl who desperately wanted to not be the token Black person in her year. People thought I was you all the time.

"I got bullied at school and would head to the library for some safety. It was there that I discovered the genre of fantasy. It was such an escape.

"And then, I began writing for my sister really. Because she had gone through a lot growing up with her illness. I was always trying to make her smile, trying to make her laugh. So I used to read her stories and I’d often progress from what was on the page. And so, this relationship developed where I was the ‘storyteller’.”

I wanted to reach through the screen and give her the biggest hug. Instead, I ask “What literary and storytelling styles do you take inspiration from for this book (and, by extension, The Ending Fire trilogy)?”

“In no particular order, here’s a list of works that have inspired me: The Broken Earth Trilogy by N K Jemisin, Earthsea Quartet by Ursula K Le Guin, The Assassin’s Apprentice by Robin Hobb, The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon, Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan, Why The Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler and Beloved by Toni Morrison.”

There’s no suffering that I’ve represented on the page that actually doesn’t come from that history in some kind of way

An obvious comparison title to help describe El-Arifi’s novel is the Legacy of Orïsha trilogy, Children of Blood and Bone and Children of Virtue and Vengeance, by American Nigerian author Tomi Adeyemi. However, El-Arifi’s book contains not only the unjust hierarchical ways of life often realised in fantasy fiction but visceral descriptions of torture and sex, too.

Suffering, violence and oppression are the background to the action and plot. “What was it like for you to be immersed in that kind of world, during the creative process?” I ask.

“I’ve deliberately woven in some of the most shocking and gruesome elements of the violence that has historically been enacted by colonising regimes and suffered by indigenous peoples. There’s no suffering that I’ve represented on the page that actually doesn’t come from that history in some kind of way.

“King Leopold II of Belgium, who ruled the Congo at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century, used atrocious methods to keep the Congo in his power including chopping off hands and feet to discipline the slave class.

“But at the same time, I didn’t want this book to be just desolate. It is a terrible, terrible world, but I didn’t want to come across as there not being any hope at all. And that’s where like this strive for rebellion comes in. And so, it’s a story of hope, because more than anything, I wanted to show that there is so much light at the end of the tunnel, even with the dark shadows of the reality of colonialism.”

“So, how does all this heaviness brush up against your creative process? Which parts of the creative process do you like the best? Which parts do you like the least?"

One of the things that’s freeing about fantasy is that I can also break free of the binary

El-Arifi says “Well I don’t plot at all. I literally just write and I write. I don’t know what’s coming next. So just I write and I write. And, for me, that’s the best bit.

“I think one of the things that’s freeing about fantasy is that I can also break free of the binary. And that was really, really fun and freeing. I’ve included non-binary characters in the book because there were many indigenous groups within Africa and many, many places in the world where there was no gender binary. And I was just like ‘Ha, I can do that in fantasy!’

“Getting the first book through edits was much more difficult than editing the second book, because I’ve grown as a writer. The first draft of The Final Strife was 70,000 words. It’s now 170,000 words... So in the editing process it’s grown by a huge amount. That was a slog for me, because I was ‘learning how to write’ whilst also expecting to be writing ‘like an author’.”

“And who do you reckon you write for?” I ask.

“Well, I’ve had mixed-heritage early readers, from different parts of the world contact me and say, ‘You know, this has meant so much’, and ‘Wow, this has been amazing and it’s proved to me that I can write about my own heritage in different ways.’”