You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Sairish Hussain discusses her new novel, family ties and the legacy of Partition

With her second novel, Sairish Hussain explores family ties in modern day Bradford and the legacy of Partition.

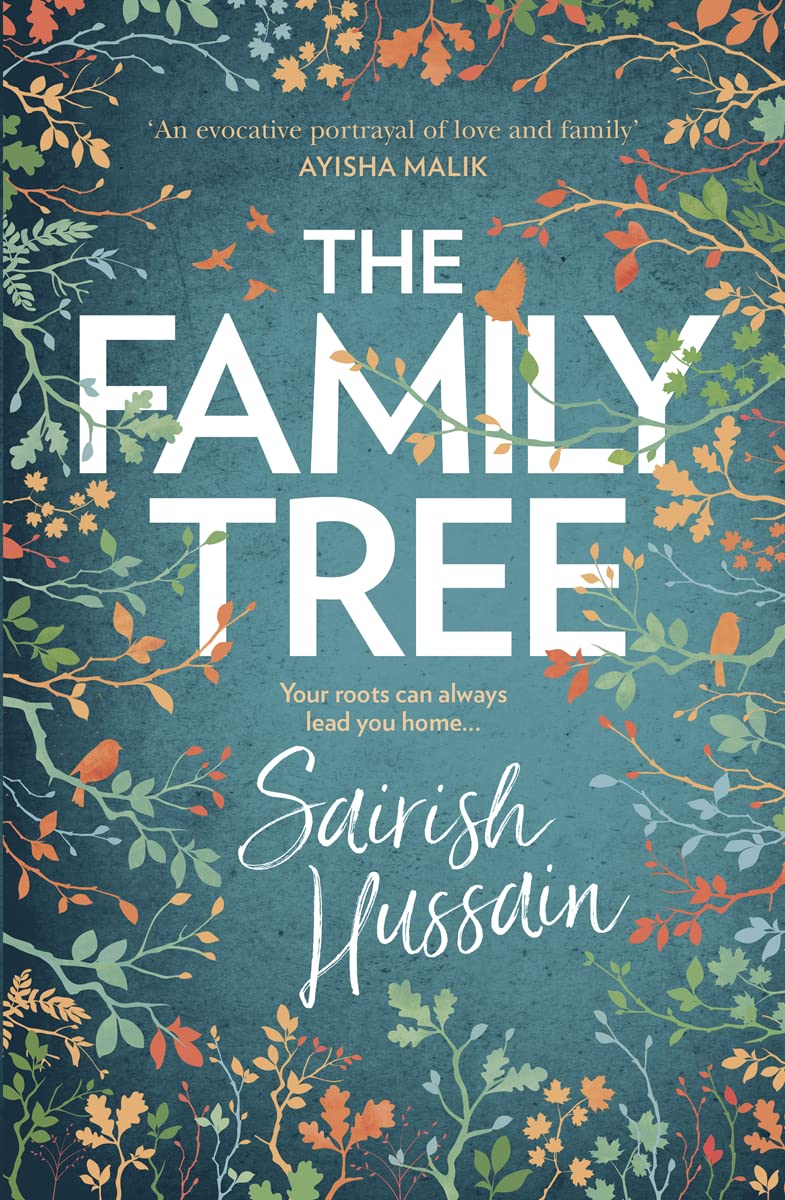

Sairish Hussain’s second novel, Hidden Fires, follows her Costa-shortlisted début The Family Tree, and is another beautifully observed multi-generational story which centres on the relationship between octogenarian Yusuf and his teenage granddaughter Rubi. The pair are forced together when Rubi’s parents are unexpectedly summoned abroad while she is in the middle of sitting her GCSEs. Unwilling to leave their only daughter home alone in Manchester, they pack her off to Bradford where widower Yusuf lives a quiet, orderly life in a small, terraced house, his days marked out by the five daily prayers and visits to the local mosque.

The novel begins before Rubi’s arrival, one night during Ramadan, 2017, when Yusuf wakes alone in Bradford from a nightmare of ash and smoke to make his Fajr prayers at 2 a.m. Switching on his television afterwards, he sees a tall building engulfed in flames. In Manchester, 16-year-old Rubi is also awake, constantly refreshing her Twitter feed, hoping that the footage of the burning tower block in London on the TV news is out of date and the fire is now out.

I’ve been fascinated by that period of history for what seems like forever

In the wake of this present-day tragedy, Yusuf’s sometimes faltering memory starts to recall an earlier tragedy that has shaped his life.

The most frequent visitor to Yusuf’s house is Ashraf, who he has known since both were young men who had made the journey from Pakistan to Bradford to work in the mills—they first met when circumstances required them to share the same mattress while working opposite shifts. Through their scenes together, Hussain skilfully reveals Yusuf’s life since coming to England 55 years earlier: one of hard work, sacrifice and duty.

In contrast, his vibrant granddaughter Rubi, whom he doesn’t know particularly well, likes to sleep in until noon when not at school, film make-up tutorials for her YouTube channel (with five followers) and fret about her weight. Yusuf and Rubi take it in turns to narrate, and their respective chapters are interspersed with Hassan’s story—Yusuf’s son and Rubi’s dad—told in the third person. There is humour to be found in the culture clash between the newly co-habiting generations, and their mutual incomprehension. Yusuf is mystified by Rubi’s septum piercing which he observes is “hanging in the middle like a door knocker”, while Rubi rails against being dragged out of her bedroom: “He called me into the kitchen for no reason but just to stand next to the oven as he stirred a pot.”

But as they spend more time together, their bond deepens. Rubi has problems of her own—related to social media and bullying—and her grandfather’s gentle insistence that she come out of her room and join him has a positive effect on her wellbeing. However, Rubi can’t help but notice that her grandfather is becoming increasingly forgetful and disturbed in day-to-day life. From Yusuf’s chapters, the reader knows that his mind is grappling with long-suppressed childhood memories of the devastating Partition of India in 1947.

I’ve been told […] I’m much better at writing characters that are as different to me as possible, and I enjoy that

When Sairish Hussain speaks to me over Zoom from her home in Bradford, she explains that she started thinking about the novel that would become Hidden Fires in 2017, when the BBC started airing documentaries to mark the 70th anniversary of Partition. She watched all of them: “I’ve been fascinated by that period of history for what seems like forever.” Already knowledgeable on the subject—she did her dissertation on the literature of Partition—the programmes struck a deep chord: “Seeing it on screen and seeing those interviews with people who lived through it was quite a life-changing experience. I think it was the emotion. Particularly the old men, it felt like, for some of them, it was the first time they had even spoken about it, the first time they’d ever been asked. And the emotion, it just poured out of them. And that’s where I found Yusuf.”

Yusuf is one of the most convincing 80-something protagonists I have come across, so I ask how Hussain managed to put herself into his mindset. “I’ve been told […] I’m much better at writing characters that are as different to me as possible, and I enjoy that”, she says. “Their life experience, their wisdom just attracts me, and I would rather write from a male point of view, because it’s different to me, and the older the better I’ve found. The more a character is like me, the more I kind of struggle.” She describes him as looking “like my granddad, like people I know in my neighbourhood, and I just thought ‘I’ve never heard this voice in fiction’”.

As Rubi notices, Yusuf’s health starts to decline over the course of the novel. Hussain says: “I wanted to get that right, it starts very slowly and the thing I was researching was the vagueness. It’s something that’s hard to describe —what does that mean, what does that feel like—I suppose it’s like remembering that you’ve forgotten something but you don’t know what you’ve forgotten and the frustration that comes with that.”

With the first novel I felt it was something I had to do, and there was no guarantee that anyone would read it apart from my mum

Hussain’s début novel The Family Tree was shortlisted for multiple prizes including the Costa First Novel Award, the Portico Prize—awarded to the book that “best evokes the spirit of the North of England”—and the Diverse Book Awards. She was also selected as one of the Women’s Prize for Fiction Futures finalists. All wonderful recognition, but which one meant the most? “I’m going to have to say the Costa because that was the first one and it was absolutely huge,” she says. “[The Family Tree] had been published, it had been out a few months and I was just a bit sad because I thought, it’s not been reviewed in any newspaper, but it was quietly bobbing along and then—whoosh!—it just exploded. I will forever be grateful to the judges.”

But the warm reception of her début didn’t make writing her second novel any easier. “With the first novel I felt it was something I had to do, and there was no guarantee that anyone would read it apart from my mum. But I had to get the story out.” The Family Tree was written as part of her PhD in creative writing at Huddersfield University, where she now teaches. “I kind of flew through it, I did it because I so wanted to do it, regardless of what the outcome would be.”

Hussain tells me she had “something of a lifelong ambition” to write about Partition “in some way”. She mentions Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie and Ice Candy Man by Bapsi Sidhwa. “I did ask myself, do we need another Partition novel?”, and then, “How am I going to approach this, what am I going to do differently? I did want to focus on the legacy and what it means now. There are people that I know, similar age to me, similar background to me, who have no idea that this thing happened.”

The exploration of grief and loss is a central strand of Hidden Fires, but it is also a story of familial love and resilience, “an unlikely friendship story between a granddaughter and her grandfather… I think it is their bond that is the heart of the story”.