You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Salena Godden discusses performance, writing and celebrating life

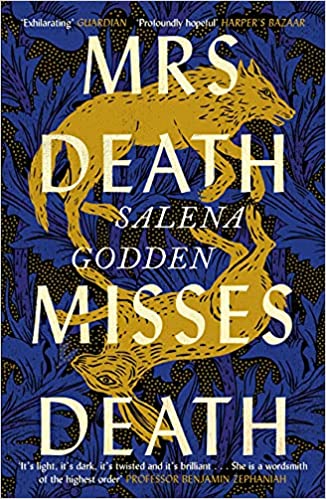

Polymath performer Salena Godden’s first novel is a riotous, time-travelling tale of death which reminds us to live well.

"It comes from a place of grieving. I was mourning, I was in a very dark place and looking for the light,” says Selena Godden, the acclaimed performance poet and now novelist, of her blazing début, Mrs Death Misses Death (Canongate). For a book about death, which it is, it is sombre and deeply moving, but also playful and exuberant; a whirl through space and time in which Mrs Death tells her story to a struggling young poet, Wolf Willeford, who becomes her scribe.

Having watched Godden performing her work on YouTube (she is an electric presence on stage) and listened to her speak on Radio 4, I was looking forward to meeting in person in east London, where she lives, but due to lockdown restrictions we must settle for a phone call. Godden has a singularly lovely voice down the line; earthy, rich and warm.

She is able to pinpoint precisely where her first novel began. “It was December 2015 and I was feeling really low, and I was really skint, as everybody is at Christmas time. December is also the anniversary of my father’s suicide and it’s when my grandmother died too, so there’s a lot of mourning and grief that comes with December—and that pressure of being jolly, ’cos it’s Christmas.” She was walking down Brick Lane (in east London) when she suddenly heard a voice say clearly: “I know a lot of dead people now.” She took her phone out and continued walking, down to Whitechapel and east towards Bow, “stopping in bus stops, typing it all in”.

I wanted it to feel like a transmission coming through the veil or through time, as if it is coming through the desk

In the novel, the line “I know a lot of dead people now” is spoken by the eponymous Mrs Death. Since the 14th century death has been personified as male; the hooded, skeletal Grim Reaper clutching a scythe. Godden’s reimaging has death as an elderly, black, working-class woman. “In the book, I wanted her to shapeshift and the shoes that she chooses to walk in are [those of] the people that are most ignored, a kind of silent scream,” says Godden. “So she’s the cleaner in the hospital, the woman selling tobacco in the shop, the homeless woman.”

After an eternity doing her job, Mrs Death has had enough, and decides to unburden herself to Wolf Willeford, a young poet who lives above an east London pub. Wolf has had a rough time of it. He first met Mrs Death aged nine, when she “took my mother in one greedy gulp of flame”, but he lived. Now, he will become a scribe to Mrs Death. Wolf acquires an antique desk, which he uses as a conduit, and the pair travel across time and space, witness to deaths past and present, as Wolf tells Mrs Death’s story across the ages—and also his own.

Part of what makes Mrs Death Misses Death so original and exciting is Godden’s freewheeling from prose to poetry to non-fiction. There are accounts of the deaths of real people woven into the narrative: these real deaths that Mrs Death speaks of are those of women whose murders have been left unsolved, or whose deaths were not seen as a priority.

Of her choice of literary forms, Godden says: “I wanted it to feel like a transmission coming through the veil or through time, as if it is coming through the desk. So they are coming as stuttered stories, or as poems, or as songs, or as broken pieces of diary.” The effect is mesmerising, and begs to be read aloud—Godden will be reading the audiobook edition herself.

“Wolf is roughly based on a very young me, I suppose,” she says, thoughtfully. “I’ve been doing poetry, and writing, and publishing and gigging since I was 19, and I’ll never forget how tough it is, you know, when you’ve got no money; no money for rent or heating. It’s based on what it’s like to be a struggling young writer in London, trying to realise your dream.”

Godden was born and grew up in Hastings, but rather than take up a place at university, she was drawn to London’s bright lights. Arriving in the capital “without a penny to my name”, she traipsed around the West End looking for work and managed to get a job backstage at “Miss Saigon”, “up in the flies, pulling in the backdrops”. It was while working for a record label that she met the Scottish poet Jock Scot, who dragged her on stage at one of his gigs, and so, in the early 1990s, her career as a performance poet began. She has since established herself as something of a cultural polymath, publishing several volumes of poetry, most recently Pessimism is for Lightweights (Rough Trade); a memoir of her 1970s childhood, Springfield Road (Unbound); her essay “Shade” appeared in The Good Immigrant (Unbound); and her 2017 album “LIVEwire” was shortlisted for the Ted Hughes Award. All while continually touring—and gigging.

Given all this, I’m very curious as to why now felt like the right time for a novel? “I don’t know!” she says, almost laughing but sounding genuinely perplexed. “Umm, I think this story just presented itself to me and it was more painful and difficult not to write it, than to roll up my sleeves and try and write it…”

a celebration of the everyday miracle of our survival, it is a salute to this life, this world and our short time here

Mrs Death Misses Death was written out of contract, and Godden says that she wasn’t sure if she was even going to show it to anyone else. “There’s a freedom there in that writing, because there was a tiny piece of me that was thinking I was just going to put it in a folder."

“I wanted to make this with no—for want of a better way of putting it—audience. I wasn’t performing, I was just making something that I wanted to think was good… I am actually quite showy-offy sometimes, especially after a few glasses of wine—‘Aah, look at this new poem I’ve done!’—but with this I didn’t let anyone read any of it.”

Her favourite time to write is the very early morning: “If you start writing at 4 a.m., you’re almost done by midday, and most [other] things can wait until after midday… In that silence and that stillness and that quiet, nobody needs you, you don’t have to feel guilty, no one is emailing you. You can just really get lost [in the work].”

For a book about death, I say, it is remarkably uplifting. There is a refrain from the novel that has been going round and round in my head since I read it: “Enjoy yourself, enjoy yourself, it’s later than you think.” An exhortation to live well now, while you can, for death is surely coming. It is, as Godden has said, “a celebration of the everyday miracle of our survival, it is a salute to this life, this world and our short time here”.

Extract

When I called for change, did you pass by me? Did you see me today?

I sit on a bench outside London’s King’s Cross station. I like train stations and airports best. I like to sit in places where people come and go. I sit and watch you come and go, you say, goodbye and hello, come and go, goodbye and hello. It’s as though you are not connected to each other. Goodbye, you say, clinging on to that last glance, you give a funny little wave. You don’t know that you don’t have to touch, to see, to feel each other. Human beings were designed to be in contact without being in contact, to communicate without words, to call each other to each others’ minds. Humans still have so much to learn about connection. But when you are in transition and whilst travelling you are tuned in to this, you are alive and alert. When you travel you wake up. You’re awake and aware of changes, differences and sameness, strangers and each other. In transit you are occupied by Time and Space, by clocks and miles, by separation and reunion, your chance and your fate. Humans were built to travel, humans were made to move, to share and to migrate, just like butterflies and birds.

If she has a hope for Mrs Death Misses Death, it’s that it helps to start a conversation “about the way we mourn, the way we talk about death and grieving”. The book was written before the spectre of Covid-19 but, in our present situation, has a particular resonance. “In a year where funerals are being reduced to only five, six people, we’re really having to find other ways to mourn, to express. I think this book is really talking about connection, and our conversations with ourselves and with each other. Just bloody reach out and tell someone you love them before it’s too late.”