You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

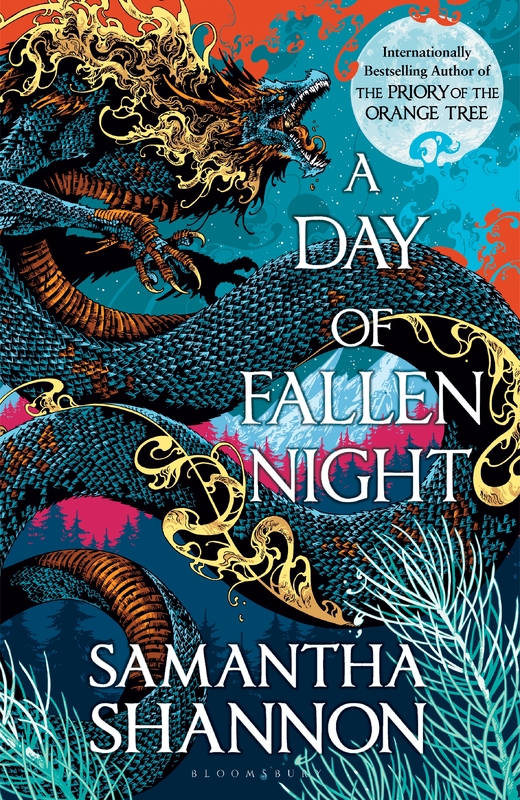

Samantha Shannon on her Roots of Chaos cycle, her love of dragons and powerful characters

Women’s empowerment is at the heart of the latest epic in Samantha Shannon’s Roots of Chaos cycle.

"I think A Day of Fallen Night is a slightly tougher book; it’s more complicated, it’s longer and there’s more politics,” says Samantha Shannon over coffee when we meet in King’s Cross. Shannon orders a latte—in need of caffeine after a detox gave her “really vivid nightmares”, including a clown forcing her to swim through a pan of tomato soup.

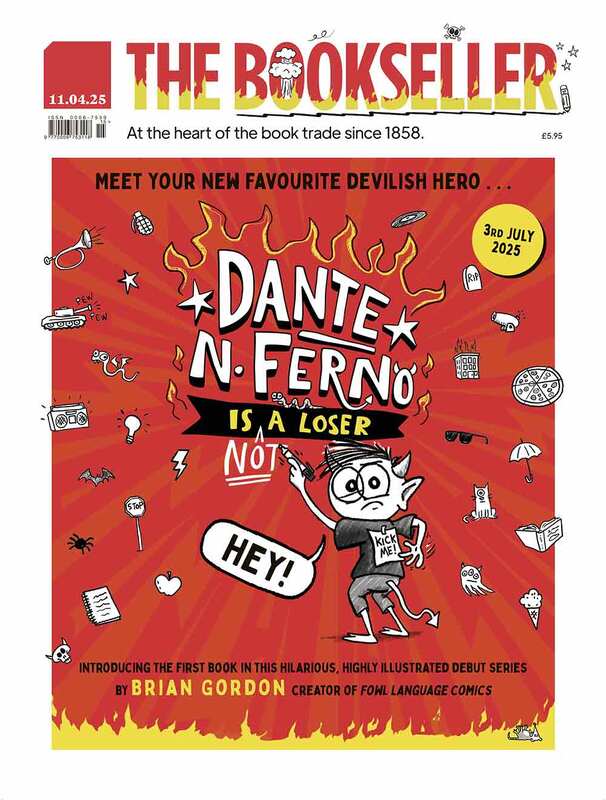

Nightmarish soup aquatics aside, we spend the next couple of hours discussing A Day of Fallen Night, Shannon’s mighty “labour of love”. It is the prequel to The Priory of the Orange Tree and the second book in her Roots of Chaos cycle. Set 500 years before the events in The Priory of the Orange Tree, Shannon charts the devastating events of four years, in four countries, through four principle narrators. We follow Glorian, heir to the Inys throne; Dumai, a devout princess of Seiiki; Wulf, a soldier of Hróth with a hidden past; and Tunuva, priestess and warrior of the Priory. An age of fire has begun: the Dreadmount volcano erupts with dragons and a fiery plague lays waste to the world. In the south the Priory—a group of female warriors sworn to guard against such evil—are called to battle. Dumai searches for a way to save her kingdom and Glorian grapples with her duty, while Wulf fights desperately to protect her and his king.

It’s been empowering for me personally to write a world which is quite women-centric and where the male characters don’t disrespect women just for being women

It is an epic read and one which was epic to produce, requiring a “heroic effort from Bloomsbury” and Shannon. Originally sent to her editors, Alexandra Pringle and Allegra Le Fanu, at 345,000 words, it was the longest piece of work Shannon had ever written. A compressed editing schedule—a result of the pandemic—added strain. While at an event in Edinburgh, Shannon was found on the final night of editing by her friend and fellow author Tasha Suri “in the hotel café, rocking back and forth with a huge espresso martini”. Yet Shannon and her editors prevailed, managing to whittle the text down to a mere 295,000 words. The final book runs to 880 pages.

Beyond the happily ever after

Shannon lost both her grandparents while writing A Day of Fallen Night, and grief informs the novel “a lot”—in an incredibly beautiful and honest way. Tunuva is a mother without a child, who carries the loss as the kernel at the centre of her being. Dumai loses her childhood friend, Wulf sees his king murdered and Glorian must bear the death of her parents: “All sense of control crumbled,” Shannon writes. “She had a sudden urge to rip and strike, run and scream, fling open the doors and run until her legs gave in—anything to be out of this room, to not have heard these tidings. Anything on earth.”

Tunuva is consoled in her grief by her Sapphic relationship with Esbar, the future leader of the Priory. We meet them decades into their relationship—two sides of the same coin, intimately bonded, yet they place duty above all else, including motherhood. To provide the next generation of warriors and care-givers, both women have children with their friends, the men who take on the domestic chores at the Priory. “It was important to me that they had children because that is often presented as the end of a woman’s story,” Shannon explains. “I thought, ‘What if I start a long way after the traditional happily ever after?’ That means it can’t be the end of Esbar and Tunuva’s story, it’s just part of the journey they have been on.”

I think it can also be powerful to show a world where there is no sexism

Both characters are magnificent, bold in battle and in love, as they lead the Priory’s warriors against the mighty dragon Dedalugun. Their enemy is the product of Shannon’s life-long love of dragons, which began when she first watched the 1996 film “Dragonheart” with friends for her sixth birthday. Although one friend had to leave the cinema screening after the sword-fighting became too intense, Shannon maintains “Dragonheart” is “the best thing I’ve ever seen”. Cornelia Funke’s children’s novel Dragon Rider was the step which led to protest: a staunch refusal to sing the lyrics “and the dragons are dead” in the hymn “When a Knight Won His Spurs” at her primary school. Little surprise, then, that the legend of St George and the Dragon, a story Shannon has described as having “roots infested with rot”, was re-imagined in The Priory of the Orange Tree.

Feminist retellings are having a renaissance both within fantasy and beyond. But for a long time, Shannon tells me, misogyny was an expected part of the genre. “Fantasy so often draws from history, as indeed I do,” but history often comes freighted with patriarchy, which is often translated into the fantasy world. George R R Martin’s Games of Thrones is an “obvious example”. “It can be empowering to see women overcoming extreme patriarchy,” Shannon says, but adds that “fantasy is the genre where we can dream beyond that. I think it can also be powerful to show a world where there is no sexism.” Yet tackling misogynistic assumptions requires conscious correction. In her début The Bone Season, Shannon used the word “whore”, but in a recent foreign-language translation she asked her publisher to remove the word: “It didn’t make sense for my character to say that. It’s just an unnecessary, misogynistic attack.” Shannon continues: “It’s been empowering for me personally to write a world which is quite women-centric and where the male characters don’t disrespect women just for being women.”

There has been such a move towards not only writing Greek mythology retellings, but also reclaiming women’s stories from history

Attention to semantics is vital not only to the politics of Shannon’s writing but also to her naming system in the Roots of Chaos cycle. The names in her novels are derived from older forms of existing languages or from extinct languages, such as Gothic and Sumerian. It may take the entire course of writing and editing to get the names right, but the detail in the results is undeniable. Dumai—“from an ancient word for a dream”—is taken from an old form of Japanese; Tunuva Melim, drawn from old Persian and Siberian, translates as “splendid strength”, a name befitting the finest spear-woman in the Priory.

Shannon’s 8,000-word “etymology document” continues to grow with each new character. Naming takes time: it’s a “fiddly procedure” trying to find “words that fit together naturally” and reflect, in some way, the traits of the character in question. The names are then run by a speaker of the modern form of the language. “I have dodged a few bullets,” Shannon laughs, as she tells me that a name which meant “softness” in the older form of the language now translates as “meat”.

Having signed another book in the Roots of Chaos cycle with Bloomsbury, we can expect more daring names and more insight into the world of the Priory from Shannon, but not before she has finished working on the fifth instalment in The Bone Season and her reimagining of the Greek goddess Iris. “There has been such a move towards not only writing Greek mythology retellings, but also reclaiming women’s stories from history,” Shannon says as she contemplates joining the “movement” with the likes of Pat Barker, Natalie Haynes and Madeline Miller. I’m sure she will be welcomed into the fray.