You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

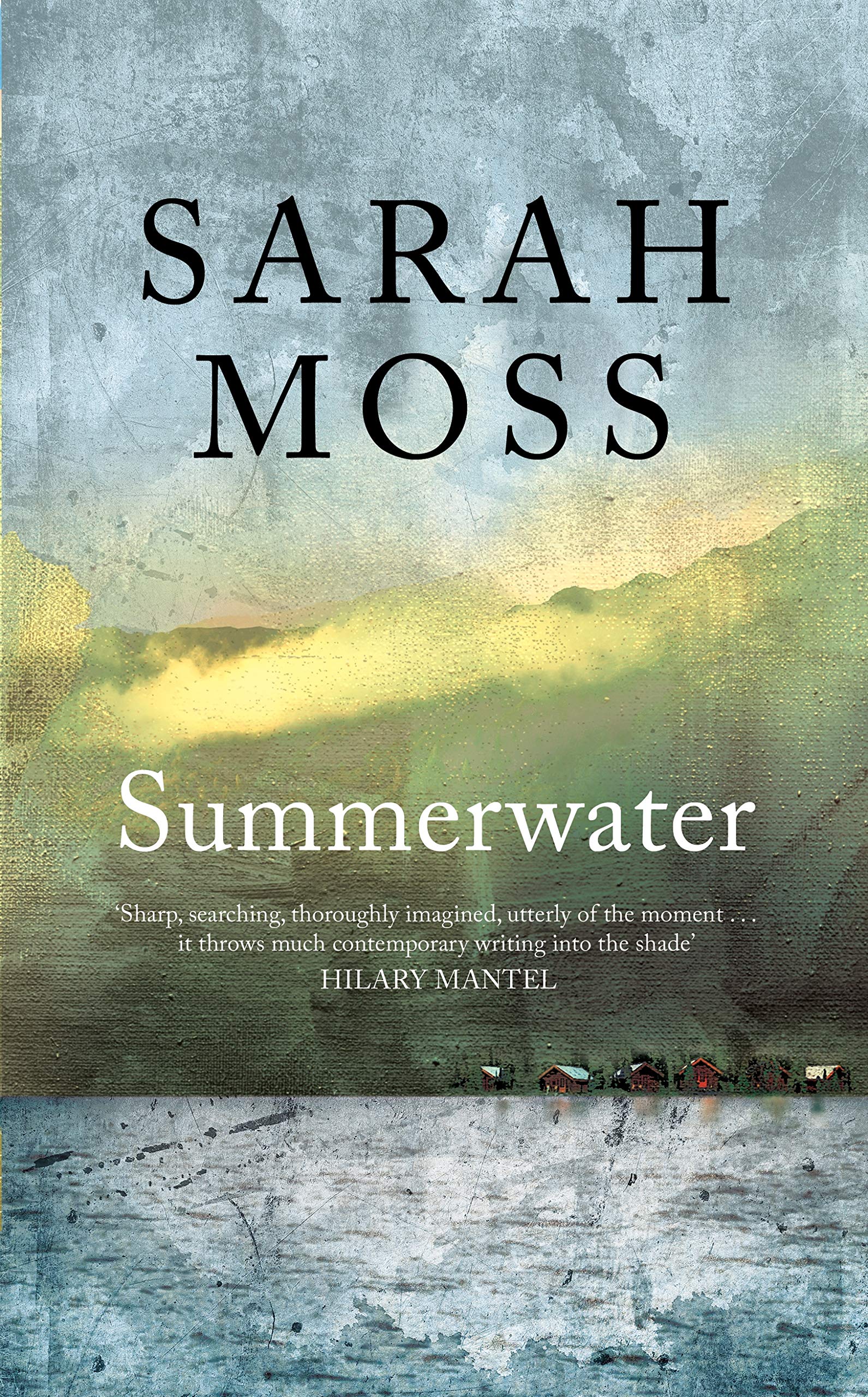

Sarah Moss discusses her seventh novel inspired from a family trip to Loch Lomond

The seventh novel by Sarah Moss is set over a single day and explores our potential for connection and for cruelty in these divided times

Since her 2009 début Cold Earth, Sarah Moss has quietly carved out a reputation as one of this country’s most interesting contemporary novelists. Her six novels to date—all published by Granta—show an extraordinary range. Max Porter, her former editor and friend, has described her work as “combining extraordinary intellectual acuity with technical virtuosity in ways very few living novelists do”.

Summerwater, Moss’ seventh novel and her first for Picador, is set on a rainy Scottish campsite over the course of a single day. The holidaying residents of six tatty cabins, cooped up with their families owing to the torrential rain, have little to do except watch each other. As we move from cabin to cabin, inside the heads of the characters—who range from pre-school children to teenagers; from fortysomething parents to elderly retirees—it becomes clear that these people, this temporary community, are riven by deep divisions; by age, by class, and along chasmic political lines.

When, owing to the coronavirus outbreak, Moss speaks to me over the phone from her home in Coventry, she explains the seed of the novel was sown on a summer holiday she took a couple of years ago with her husband and their two boys, on the banks of Loch Lomond. It rained, “all the time, every day” she recalls, with a smile in her voice, meaning most people were confined to their cabins. “I was fascinated by the way that a community didn’t develop. There were more cabins than there are in the book, maybe 12 or 15, there were people in all of them, but there was no conversation. I’m sure we were all watching each other, certainly we were watching them… A lot of families barely seemed to be leaving the cabins. I was just very intrigued about what might be going on [inside].”

Like several of my novels, in some ways it’s a novel in which nothing happens until the end—when it really does!

Within the fictional cabins of the novel, with their softening wooden walls and cheap plastic windows, much is going on behind the flimsy doors. There are internecine squabbles between families stuck in a small space together, but also tenderness and humour; a mother to a baby and a toddler, suddenly realises her children won’t always love her this much.

But there are tensions between the cabins, and one family—a mother, Alina, and her young daughter, Violetta—draw particular animosity. They are not dressed like the others, and they don’t behave like the others; playing loud music into the night and holding parties. Most significantly, they are not British. This is a post-Brexit novel and the attitudes of the characters run from overtly racist—that foreigners should have gone “home” by now—to the more subtle. Teenager Becky is the only person who speaks to Alina, when she wishes Alina “good morning” in Polish (although Alina is in fact Romanian) as she passes her cabin, something she has learnt at school in the era of free movement across the EU.

Sense of unease

There is a sense of unease from the beginning of the novel, one that builds, almost imperceptibly, to a deafening thrum of dread and a devastating ending. It is technically brilliant—how did she do it? “It’s a writerly challenge,” she says. “It has to be enough but not too much and it has to rise through the novel so that you don’t realise the point at which you started hearing it. It’s like having a background noise that very gradually gets louder. You don’t want the reader to think, ‘Oh, hang on a minute, what’s that?’ You just want it to gradually get louder.” Later, she adds: “Like several of my novels, in some ways it’s a novel in which nothing happens until the end—when it really does! So, you need to get the shadow of that ‘happening’ spreading over the whole novel, from the beginning.”

For all that, Moss describes Summerwater as “a playfully written book”. She started it as a “distraction project” from the novel she was supposed to be working on, and became much more interested in it than her original novel. “I was trying to write a technically challenging novel that wasn’t quite lighting up, and this was just a little thing to do on the side because it was more fun. I sometimes wonder if that’s how I need to write at the moment... I always have an eye out for what the thing I’m writing is cover for.” She adds: “Both this and Ghost Wall I wrote much less diligently than most of the other [books]. I think that’s something about the small book that makes me think I can experiment and play a bit more and not worry, not need to have the whole thing perfectly arranged first, because if it goes wrong it’s easy to backtrack and re-do.”

I would want to make sure that anybody who was aspiring to be a novelist has read 18th and 19th-century fiction as well as contemporary stuff

The first draft of Summerwater took just three months—Moss is a proponent of the “write fast and edit slowly” school of thought. She is also, impressively, a full-time academic, who writes around her day job, although when I ask about this she starts laughing. “One might say that I fit full-time lecturing around my writing some of the time.” She began her academic career at Oxford, specialising in the Romantic period with a DPhil and a research fellowship, before moving to the University of Kent to lecture, followed by a year at the University of Iceland, which inspired the memoir Names of the Sea: Strangers in Iceland. Posts at the University of Exeter and the University of Warwick followed, and she was due to move to University College Dublin in May, before the coronavirus pandemic put paid to anyone moving anywhere.

Novel histories

Moss teaches creative writing now, but in “a very literary way”, she says, believing that her students “need a sense of the archaeology” of the novel. “I would want to make sure that anybody who was aspiring to be a novelist has read 18th and 19th-century fiction as well as contemporary stuff, and can trace the path of the development of the form of the novel.” Teaching creative writing is so interesting, she says, “because you are never teaching people how to write, you are teaching them to work out how they write”.

Summerwater unfolds within a single day. Moss was thinking of the circadian novels of Virginia Woolf and Rachel Cusk’s Arlington Park, and says: “I wanted to do an intense close reading of time and place. That focus you get when you are isolated and your movements are restricted; the detail in which you start to see the place to which you are restricted.” Each chapter of the novel is interspersed with a short section about the natural world—from the making of an anthill to the planes flying overhead—of which the characters are a part, although they are oblivious.

Moss is exploring the nature of community, and how communities form or fail: “One of the questions I was thinking about was, whether in this completely divided and fractured country, between England and Scotland, between Leave and Remain—all of those dividing lines that, at least until this pandemic, felt absolute and terminal—is there enough left that we can respond to in an emergency? And of course, that’s the question that we are now all answering. And I still don’t know,” she says, thoughtfully. “That was the hypothesis of the book: even if we all hate each other and we’re all deeply suspicious and we all want each other to leave, and each of us thinks the other has destroyed the country, come the fire, are we capable of a humane community response?”