You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Sathnam Sanghera in conversation about his first children's book on the British Empire

Charlotte Eyre

Charlotte EyreCharlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed ...more

Award-winning author Sathnam Sanghera outlines the differences between writing for young people and adults in his take on the history of the British Empire.

Charlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed ...more

Sathnam Sanghera, the journalist and award-winning author of Empireland (Viking), didn’t initially want to write a book for children about the British Empire. “Another publisher approached me and I didn’t want to sanitise the history,” he says. “That’s what Britain has always done, sanitise the history, the violence, and I assumed if you wrote for kids there would be a lot of that.”

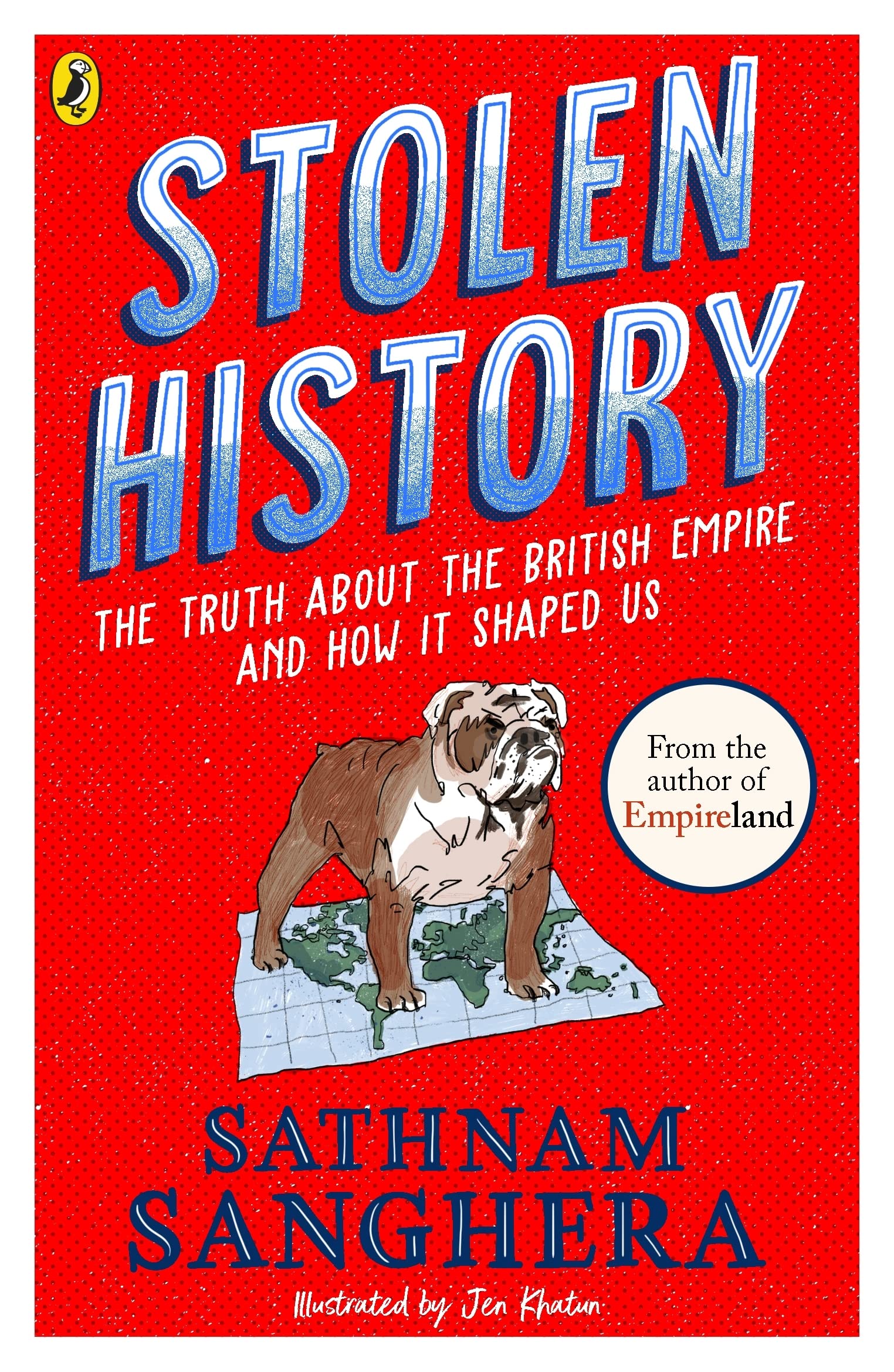

Luckily for readers, Puffin, another division of Penguin Random House, persuaded him that there was a way for him to tackle the subject and the resulting title, Stolen History, covers everything from the East India Company and the slave trade to the origins of the Boy Scouts and Wembley stadium. There are short biographies of Sir Walter Raleigh, Charles Ignatius Sancho, Robert Clive and more, and tips on bringing up awkward conversions or organising debates about reparations at school.

Every 10-year-old I know is highly opinionated and they are able to deal with the idea that there are conflicting views. I think we don’t give kids enough space to be able to handle that

Writing the book was a “long process” and 80% covers topics that didn’t feature in Empireland, says Sanghera. An entire chapter on economics, which took up four months of the author’s life, didn’t even make it into the final version.

“Empire is such a complicated subject. It’s a complicated subject for adults,” he says. He is clearly, to take just one example, no fan of the East India Company but boiling down what it was to one simple explanation just isn’t possible. “It was really racist, but at other times, British people in India were getting married to brown people in India and they had quite liberal attitudes.”

Forming opinions

Something that really comes across in the book is Sanghera’s faith in young people (PRH is pitching Stolen History at readers aged nine plus) to form their own judgements about the British Empire, or indeed, anything to do with that period. As he says, Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book can be read as an allegory of empire but readers should form their own opinions about any books, including this one.

This was partly because he didn’t want to be accused of being a “culture warrior”, and he doesn’t want parents, many of whom have “complicated politics”, to reject his book, but he also strongly feels that children and readers can be trusted. “Every 10-year-old I know is highly opinionated and they are able to deal with the idea that there are conflicting views. I think we don’t give kids enough space to be able to handle that.”

What are the other differences between writing a book for adults and one for children? Stolen History was more heavily edited, a process he enjoyed. And this was the first time he had worked with an illustrator—Jen Khatun, who is of Bangladeshi/Indian heritage.

A lot of thought went into what to show and how to represent empire pictorially. “How do you depict slavery? Should you show [enslaved people] working with cotton or sugar cane? Cotton is a crop more associated with American slavery and sugar is more imperial, more Caribbean… When you are illustrating Kipling’s Jungle Book do you echo his imperialist view of Indians? Or do you modernise? Every illustration is a potential explosive area.”

Move into writing history

Sanghera is a highly respected journalist and author —his memoir The Boy in the Topknot, about growing up in Wolverhampton in the 1980s, was published in 2009—but his move into writing history was somewhat of an accident. Before Empireland, he wanted to write a novel or biography about Dean Mohamed, a man who set up a massage parlour in Brighton that was attended by George IV. During his research Sanghera found out that Mahomed had at one point in his life served in the East India Company and the author realised he knew very little about the empire that had shaped this inspirational man’s life.

He switched to writing a history of empire and during that process the murder of George Floyd happened. People were suddenly very interested in systemic racism and colonialism and Sanghera found he was writing a very timely book.

There was some backlash and the author received a number of abusive emails and letters, and encountered angry reactions (usually from older men) at literary festivals, but there was a lot of support, too. Empireland received rave reviews and won the British Book Award for Non-Fiction: Narrative in 2022. There was also a documentary for Channel 4.

With adults it feels like I’m lecturing them, whereas with younger people I’m learning a lot from them

But one of the best things was how the book was taken up by teachers and young people, helped by PRH’s donation of 15,000 copies to schools in the UK.“I spoke at The Camden School for Girls and the questions were next level,” he says. “They knew so much. I didn’t really know the British imperial history in Iraq but someone told me that the British had a mandate that caused a lot of problems. With adults it feels like I’m lecturing them, whereas with younger people I’m learning a lot from them.”

Sanghera is currently working on a book called Empire World, in which he examines the legacy of the British Empire around the world, and has also set aside a few weeks to visit schools to promote Stolen History when it is released in June.

Extract

Although Britain was officially a Christian country, people of different religions settled here too. The first mosque was built in Britain way back in 1889 (the Shah Jahan Mosque, Woking). And it wasn’t just Black and brown people who emigrated either. At one stage Ireland was a colony of Britain, and many Irish people moved here as well.

Immigrants formed communities in places where they could find work, such as by docks or industrial areas. Some studied law, or became actors, sportsmen or doctors and nurses, such as Mary Seacole.

During the two world wars, millions of citizens from the colonies fought and died alongside British soldiers. Then, in 1948, after the Second World War, something happened that lots of people don’t know about — at least, I didn’t before starting to research this subject! The government passed The Nationality Act. And it was a huge deal. It basically gave everyone who lived in the colonies the right to live in Britain. At the time that was a staggering 600 million people — around nine times today’s population of Britain.

“I will ask the children to interview me because the amazing thing about young kids is that they ask wild questions. You never know what they are going to ask.”