You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Simon Stephenson discusses film inspirations, artificial intelligence and the search for meaning

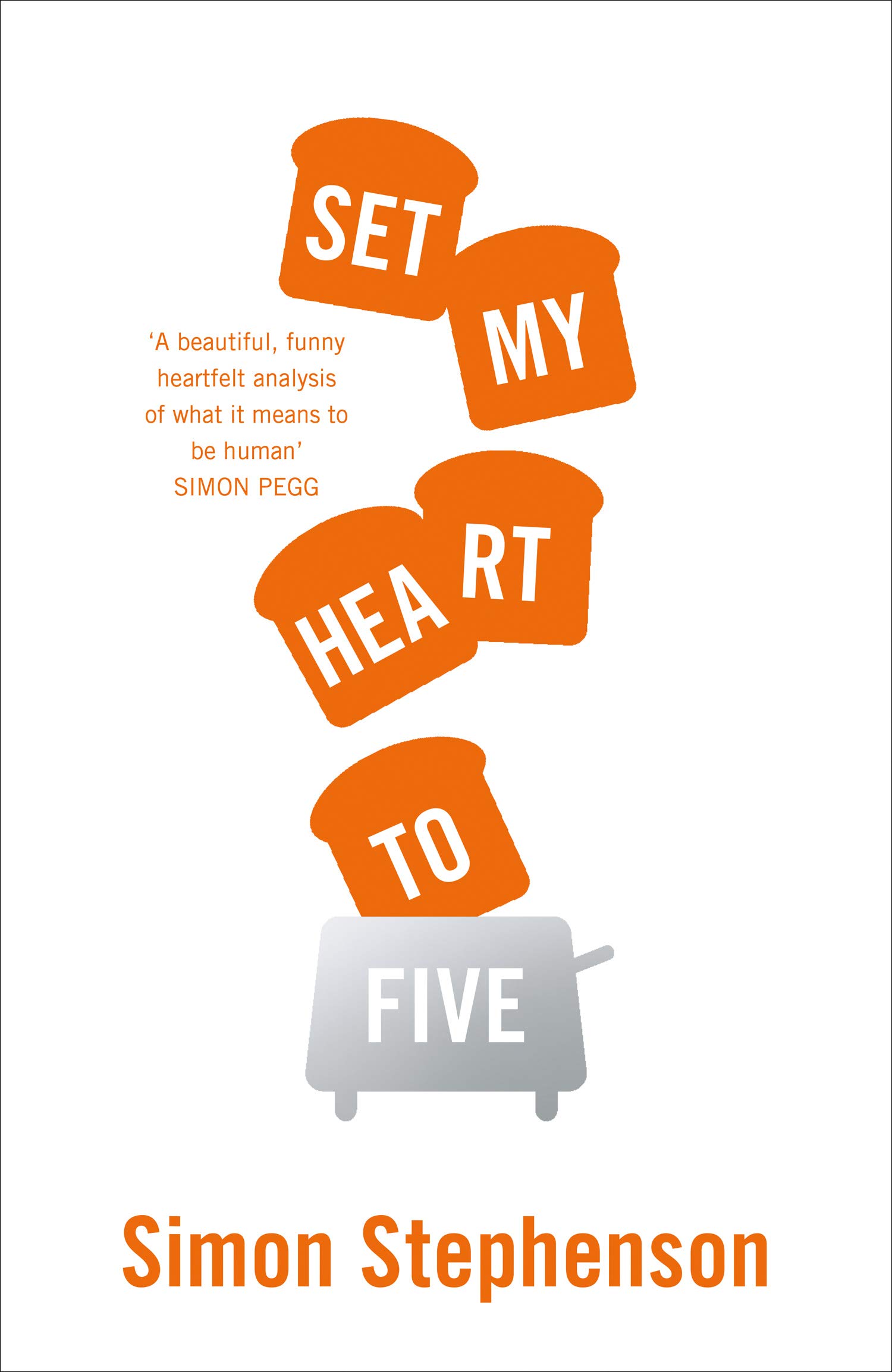

After a career as a paediatrician and screenwriter, Scottish author Simon Stephenson has conjured up one of 2020’s feel-good novels

On the rainy, windswept day I am due to meet Simon Stephenson in London, the Guardian runs a comment piece which asks: “If a novel was good, would you care if it was created by Artificial Intelligence?” Stephenson’s terrific début novel is self-evidently not written by a robot, but it is narrated by one—Jared, a “bot” dentist from Michigan—and I doubt I’ll encounter a more endearing, more joy-provoking character this year.

The year is 2054 and Jared is toiling cheerfully away at the mouths of humans. It is the perfect job for a bot as they have a complete inability to feel empathy, or indeed any feelings at all. He is programmed only to work and, as he says, “I can no more feel than a toaster!” But that is about to change. His (human) colleague Dr Glundenstein recommends watching old movies, and Jared starts to experience something beyond his understanding: feelings.

Soon, these “feelings”, and his burgeoning love of films, will propel him across the country to Los Angeles, where he plans to write a movie that will convince humans that he, and all androids, should be permitted to “feel”. America has a significant android population but humans tend to fear or despise them—the most popular movies at the multiplexes all involve “killer bots”. Heading west on his adventure, Jared is pursued by the inept Inspector Bridges of the Bureau of Robotics, who intends to “wipe” him.

It’s a story about the universal search for connection and the person searching for connection just happens to be an android

Set My Heart to Five is also a novel about Jared’s touching and often laugh-out-loud-hilarious attempts to understand and communicate with others. “It’s a story about the universal search for connection,” says Stephenson, “and the person searching for connection just happens to be an android”. He still speaks with a soft Scottish accent despite being based in San Francisco, where he now works as a screenwriter, and his route to the West Coast is an interesting one. As a teenager he had to decide between reading Medicine or English Literature at university, and opted for the former—he blames the popularity of “ER” at the time. But he always wrote stories. Aged 23, he took six months out to write “my great literary book of short stories... But thank God nobody published them, or we wouldn’t be sitting here today!” One story was made into a short film, which led, eventually, to him working as a television screenwriter in London.

Hit by tragedy

His life changed forever though, with the loss of his beloved elder brother in the Indian Ocean tsumani. He wrote a memoir, Let Not the Waves of the Sea (2011), about this experience. “Profoundly moving... it is impossible not to be touched,” found the Observer, and the Sunday Telegraph called it “remarkable”, noting that “seldom will you find grief anatomised quite so acutely and honestly”. He had planned to write a novel afterwards, but found nothing quite worked. “The book about my brother had been so essential to me to write, I couldn’t not write it. It felt impossible to start something else and write a story for the sake of it.”

So he went back to his job at a London hospital, in paediatrics, and wrote a screenplay instead—about a depressed paediatrician. To his surprise, it became the “hot script” in Hollywood for a few weeks and was the subject of a bidding war, which eventually led Stephenson to Pixar Animation Studios.

I want [the reader] to experience it through Jared’s perspective. If you don’t [know the films] I would love the book to work without them

Stephenson’s love of film, and the film industry, is evident in the novel: “I wanted to write something that had the feel and the scale of the movies that I grew up with.” Jared’s narrative is interspersed with scenes from the screenplay he is writing, with the help of his “bible”; Twenty Golden Rules of Screenwriting by R P McWilliam in which Stephenson pokes gentle fun at the plethora of screenwriting guides. In LA, these go in and out of fashion and “every meeting you go to, the studio execs have read that same book”. A few years ago, he tells me, the “big” screenwriting book was Save the Cat. The idea was that, to make your character appealing, they have to save a cat from a fire. In the novel Jared does save a cat—an in-joke. Stephenson tells me about going to meetings with big-name film directors: “You are supposed to tell them that you love [Japanese director Akiro] Kurosawa, and I always blow my shot at the job by saying ‘I love “Forrest Gump”’, haha. It is a brilliant movie.”

Screen time

As part of his education, Jared watches a series of classic films from the 1980s and ’90s. Stephenson deliberately doesn’t name these—“I want [the reader] to experience it through Jared’s perspective. If you don’t [know the films] I would love the book to work without them”—but it’s great fun to try and work them out. It’s also a refreshing change, I tell him, to read a novel set in a future where the world hasn’t totally gone to shit. Stephenson laughs. “I love the dystopian as much as anyone else... but part of the conception of the book was—what if the future isn’t awful, but just a little bit worse? And worse in a human way.” In the novel there has been a Great Data Loss, but it not was caused by war, or disaster, but by people forgetting their passwords.

Extract

Because the precious thing that sets humans apart is their feelings.

And as a bot I am specifically designed and programmed to be incapable of feelings.

I can no more feel than a toaster!

Ha!

BTW that is a hilarious joke because the programming language I run on was

in fact first developed many years ago for use in the domestic toaster.

Here is something curious I have observed about humans: informing them I am incapable of feeling often makes them feel sad. I suspect they believe they are being empathetic, but in fact they are being paradoxical. After all, feeling sad in response to someone telling you they lack feelings is like running a marathon in response to somebody telling you they lack legs.

Truly, if I lacked legs and somebody ran a marathon on my behalf I would not

consider them empathetic.

I would consider them confused!

Nonetheless, it makes them sad, and making humans sad goes against my core programming. If ever I accidentally render a human sad in this way, I therefore quickly employ self-deprecating humor to amend the situation with reassuring levity.

So I tell the human they can think of me as a microwave oven with feet!

A mobile telephone with arms!

A toaster with a heart!

In telling the story of a bot’s emotional awakening, Stephenson illuminates what it means to be human: to try, to fail, to hope. Jared’s voice is a joy; as distinctive and true as Adrian Mole or Christopher Boone (The Curious Incident...). Of his book’s potential readers, and it deserves many, Stephenson says: “Mainly, I would like people to ‘feel’. That’s what we are always striving to do in film, where the big metric is ‘can you make people feel?’, and I think that is purpose of most art, right?”