You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Sophie Elmhirst on discovering the remarkable story of Maurice and Maralyn

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson worked as a Waterstones bookseller, and as a book publicist before becoming a freelance writer in 1997. The Bookseller’s

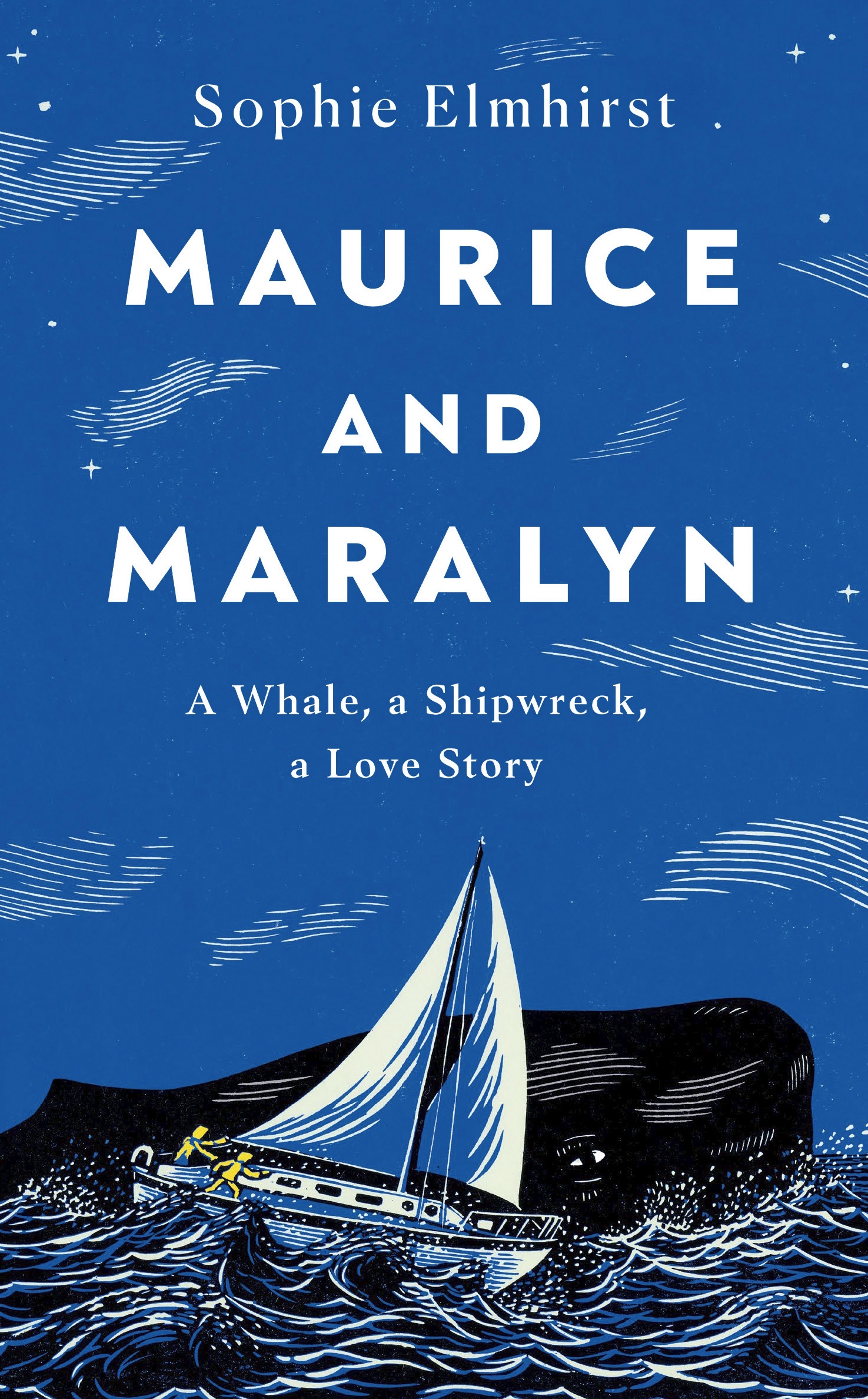

...moreAward-winning journalist Sophie Elmhirst tells the remarkable story of a couple lost at sea for more than 118 days after their yacht sank in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Husband and wife, Maurice and Maralyn couldn’t have been more different: he was cautious and awkward, she was charismatic and daring. But their yin-yang romance worked: she gave him confidence, he gave her freedom. So when—deeply bored by suburban English life—Maralyn suggested they sell their house, build a boat, set sail for New Zealand and leave Blighty forever, Maurice was game for the adventure. After months of saving and preparation, they set sail across the Atlantic. But once through the Panama Canal, disaster struck when their beloved boat “Auralyn” (her name combined their own two) was hit by a whale. It sank in a jiffy and the pair were cast adrift in the middle of the Pacific Ocean with no motor or radio transmitter. As they battled to survive on a tiny life raft, their relationship was put to the sternest test imaginable.

Already garlanded with praise from Rachel Joyce, Colin Thubron and Oliver Burkeman, Maurice and Maralyn: A Whale, a Shipwreck, a Love Story by award-winning journalist Sophie Elmhirst enthrallingly retells the story of their 118 and a third days at sea. It begins at the moment of shipwreck and then loops back to chart how Maurice and Maralyn meet, fall in love and become shipmates; and then continues the story of their lives after being rescued. It combines captivating adventure on the high seas with the story of a relationship in all its tidal states. Writes Elmhirst: “For what else is a marriage, really, if not being stuck on a small raft with someone and trying to survive?”

I wanted to convey Maurice’s adoration of Maralyn and his respect for her and her skills, all the skills that he felt he lacked. And also Maralyn’s pragmatism and stoicism

When we meet at her publisher’s office, Elmhirst—a long-form feature writer for the Guardian Long Read and the Economist’s 1843 magazine, and a contributing editor at the Gentlewoman and Harper’s Bazaar—tells me that she first came across Maurice and Maralyn’s story during the pandemic winter of 2020/1. “It was cold and miserable and I was sitting at my desk with the kids going crazy downstairs.”

Dreaming of escape, she came across the website paradise.docastaway.com, run by explorer and entrepreneur Alvaro Cerezo who collects stories of people stranded and cast away. “Nestled among them I found a picture of Maurice and Maralyn and I was immediately struck by the idea that such an adventure might happen to a couple.” Soon Elmhirst was hooked on their exploits: “fascinated by the fact that they were English, fascinated by the fact that they had been adrift for so long. I’d never heard of them and yet theirs was an extraordinary story— how had it got lost?”

Rescued from obscurity

Embarking on her mission to rescue Maurice and Maralyn from obscurity, Elmhirst was able to mine a considerable amount of first-hand material: including Cerezo’s filmed interview with Maurice not long before he died in 2017; the couple’s several published books, including their first-hand account of the shipwreck published in 1974; and the pages of Maralyn’s diary which Cerezo had photographed and uploaded to his website. “Written in the moment while at sea, Maralyn’s diary was gold dust,” Elmhirst tells me. “When I read it, I knew I was in the presence of amazing characters; people I longed to know more about.”

I realised that this was a book about two different forms of isolation. A literal shipwreck, and then Maurice’s emotional shipwreck after Maralyn’s death

Sections of Maralyn’s diary are reproduced in Elmhirst’s book too, notably her marvellous inventories and menus. Soon after being shipwrecked, Maralyn concentrated on listing the worldly goods that remained to them (“two blue bowls, one round bucket, one oblong bucket…”). But then later as the couple begin to starve and sicken despite catching and eating fish, turtles and seabirds, her lists take the form of food fantasies, including menus for dinner parties and a list of cakes. “As her body shrank, Maralyn built herself out of words, sentence by sentence,” writes Elmhirst.

Maurice and Maralyn’s own first-hand accounts of their adventure are told in a matter-of-fact manner, with their feelings only rarely expressed. This gave Elmhirst the creative challenge of filling in the emotional gaps. “I wanted to convey Maurice’s adoration of Maralyn and his respect for her and her skills, all the skills that he felt he lacked. And also Maralyn’s pragmatism and stoicism, born of being part of that cash-strapped, post-war generation which just got on with it and coped.”

Maurice and Maralyn is an outstanding example of how a gifted writer of narrative non-fiction can breathe thrilling new life into an existing story. “You have to credit the truth and pay homage to it when writing non-fiction, but that doesn’t mean that you have to sacrifice story and character and all those things that make fiction great,” says Elmhirst.

Emotional shipwreck

In the final section of the book, Elmhirst relates how Maurice spent his lonely latter days after Maralyn’s death from cancer in 2002, writing hundreds of letters charting his life with her. “He writes incredibly openly about his state of mind. And it is this latter period that, for me, gave Maurice and Maralyn’s story not just plot but depth. For rather than being merely an account of their shipwreck, it also became the story of its aftermath. What’s it like after you’ve had an experience like that? And then how is it to lose the person you shared that experience with, the person who was your partner for 40 years? I realised that this was a book about two different forms of isolation. A literal shipwreck, and then Maurice’s emotional shipwreck after Maralyn’s death.”

While vividly evoking the early 1970s period in which it is primarily set, Maurice and Maralyn is a story with resonance for our own times, not least in the way it channels a desire to escape a country plagued by strikes and political turmoil. It is also a book about the wonders of the natural world, and what we gain spiritually from being at one with them. “I find that incredibly moving—that sense that even though this nightmarish thing happened to them, it was also in a funny kind of way the sort of existence that they’d always wanted.”

Extract

On a wet November evening in 1966, Maralyn stared out of the window as raindrops chased each other down the glass. It was damp and cold and dark, everyone tucked up in their houses for the long night, curtains drawn.

“Suppose”, she said to Maurice, “that we sold our house, bought a yacht and lived on board”.

It sounded absurd. Why would they sell the house they’d only just managed to buy? Admittedly it was the only way they’d ever be able to own a boat. Prices of yachts were rising faster than wages and they’d only saved a tiny amount of Maurice’s earnings. But still, they weren’t the kind of rash people who sold their home. At least Maurice wasn’t. He felt stifled by domesticity and work, but that was just life. They had achieved what they were supposed to achieve. They were safe on their own patch of land. You don’t mock such hard-won stability. You certainly don’t sell it off.

“You’re not even trying”, said Maralyn. In the grip of an idea, Maralyn could drill through rock.

Ultimately perhaps, Maurice and Maralyn—published in the month of Valentine’s Day— is a story about how our relationships with others anchor us during those times when we feel adrift. Says Elmhirst: “As much as they craved escapism, what they both discovered, and what Maurice sadly realised even more when Maralyn died,

was the importance of human inter-dependence. That’s how we survive.”