You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Tana French in conversation about Westerns and the centrality of character

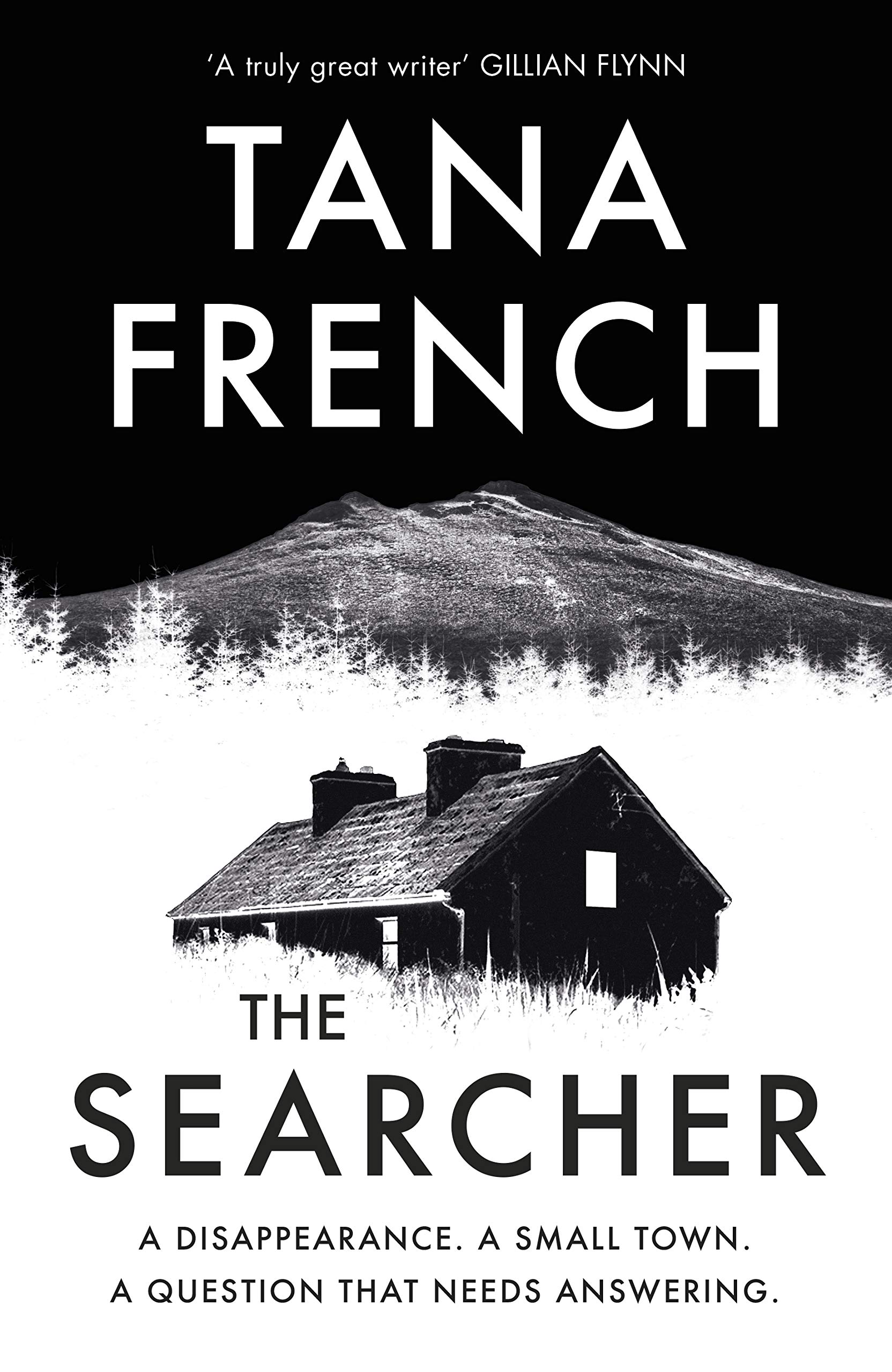

Tana French’s follow-up to the critically acclaimed The Wych Elm combines a mystery with the spirit of a Western

"I’ve discovered that as a writer I don’t like being in my comfort zone. I think it’s dangerous.”

Tana French first made her name with the Dublin Murder Squad series (six books to date), which began with her award-winning début Into the Woods. Last year she moved to Viking with her first standalone, the devastating psychological mystery The Wych Elm, which drew huge acclaim from the critics, with the Times comparing it to Donna Tartt’s The Secret History.

Her latest novel is another standalone and, interestingly, another departure; a mystery infused with the spirit of a Western. The Searcher tells of a 48-year-old Chicago police officer who has taken early retirement and moved to the rural west of Ireland with the intention of doing up the crumbling 1930s house he has bought. After 25 years in the force, and still recovering from the collapse of his marriage, Cal Hooper is looking forward to a quiet life.

The locals of Ardnakelty seem, for the most part, welcoming. Cal’s closest neighbour, garrulous sixtysomething Mart, is actively friendly, and the old fellas in the local pub, Seán Óg’s, are tolerant of the American outsider. But the first sign that this remote spot may not be the sanctuary Cal was hoping for is the uncomfortable feeling that he is being watched. This turns out to be Trey Reddy, a skinny 13-year-old with a buzz cut. At first Trey seems content to hang around, helping Cal with basic carpentry and shovelling down any food on offer. Mostly silent (but with an impressive repertoire of teenage shrugs), Trey eventually reveals why he has come to Cal; his 19-year-old brother Brendan Reddy has been missing for months, and nobody seems bothered.

Cal has no intention of getting involved with a missing persons case, especially when Brendan may have legitimately left home (a small house crammed with six siblings). To join his father perhaps, who abandoned the family for London years earlier? But Cal’s training kicks in, as well as a feeling of fatherly protectiveness towards Trey—he has a strained relationship with his own daughter, back in the US—and he senses an unresolved case that he just can’t walk away from.

One of the things I love about Westerns is that they deal very matter-of-factly with the complexity of morality; with the fact that sometimes good people do bad things

When French talks to me from her home in Dublin, the city she has lived in since 1990, she explains that The Searcher grew out of a desire to write something very different from her previous novels. Most interestingly, she had been reading a lot of Westerns and saw many parallels with the west of Ireland, “a place that is so geographically far removed from all the centres of power and law-making”, and “a wild landscape that demands real mental and physical toughness and endurance from anyone who wants to make a living out of it”. She decided to take some of the tropes of a traditional Western and transpose them: “Like the old gunslinger who is pulled out of his retirement for one more quest; how would it change? What would stay the same and what would shift, if you [changed the setting to] the west of Ireland? So I wound up with this!”

Character focus

In sharp contrast to The Wych Elm, a psychological mystery “which was all about what happens inside someone’s head”, French says she wanted to write a book where the main focus was on the main character’s actions rather than his internal thoughts. “For me, the main character shapes the book—the book is the world of the main character—so he needed to be someone for whom actions are important,” which is why the book is written in the third person.

Cal is a man with a strong moral code who finds it tested over the course of the novel. Again, French was influenced by her reading of Westerns. “One of the things I love about Westerns is that they deal very matter-of-factly with the complexity of morality; with the fact that sometimes good people do bad things, and vice versa.” In French’s novels good people can find themselves in a situation where there is no “right” thing to do. “I was thinking a lot about that, in a time where I think there’s always an impulse to make morality simple; to go, well, this person liked a really horrible comment on Twitter—so they are an evil person. End of story.”

The Searcher may be inspired by the Western oeuvre, but it also works as a sort of state-of-the-nation novel, as all good crime novels do, by revealing the concerns of wider society beyond the actual crime. “Murder happens in any society, in any time or place,” observes French, “but the reasons [why] it happens vary widely and [those reasons] tell you something about the dark places and the fears of that society.” Just as French’s previous novels have been set against the background of the Celtic Tiger boom and crash, The Searcher explores the dangers in rural Ireland, both old and new. There is the blanket condemnation of the fatherless Reddys, for example: they are a “bad family” the locals tell Cal, and not to be trusted. There is a reluctance to involve the authorities, from social services to the garda. People stay silent and mind their own business, as Cal discovers when he starts to investigate.

If I write a line and then say, ‘Oof, I could not say that on stage’, then maybe the line needs to change!

As a retired detective from another country, Cal obviously has no badge and no gun—and therefore no authority. He does have a cop’s instinct but, as he discovers, it will only take him so far. “I really wanted Cal to be in a situation where he was so out of his depth, so in a foreign country, that nothing was what it seemed,” says French. “Especially if you are moving to another country where you speak the language, it’s very easy to think that you ‘get it’, that you understand how this society works… I wanted him to be discovering, little by little, as the book went on, that he actually had no idea what was going on in this place.”

Dealing with dialogue

French, who was born in the US and then moved around a lot with her father’s job as she grew up—Ireland, Italy, the US and Malawi—says: “That idea that you need to learn a whole cultural language every time you move, regardless of whether you speak the actual language or not, is something I’ve always been very interested in.” She trained as an actor at Trinity College Dublin before making the city her home, and then worked mostly in the theatre. Great training for a novelist, I suggest, and she agrees, saying it has made her ear for dialogue particularly strong. “If I write a line and then say, ‘Oof, I could not say that on stage’, then maybe the line needs to change!”

In The Searcher there is resolution but, depending on your point of view, not necessarily justice in the traditional sense. French agrees. “In a lot of crime novels everything is neatly wrapped up, the bad people are put away, the good people are free to go on with their lives. I really like those books, they have an important function: there’s a catharsis to them in a [real] world where it feels that never happens. But you also need the books that don’t do that, that refuse to let it be that simple—and those are the ones I end up writing. I end up getting my characters into situations where there isn’t necessarily one right answer that will put everything back where it belongs.”