You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Tania Branigan discusses her exploration of China's Cultural Revolution

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

Former China correspondent Tania Branigan’s début tackles the legacy of the Cultural Revolution.

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

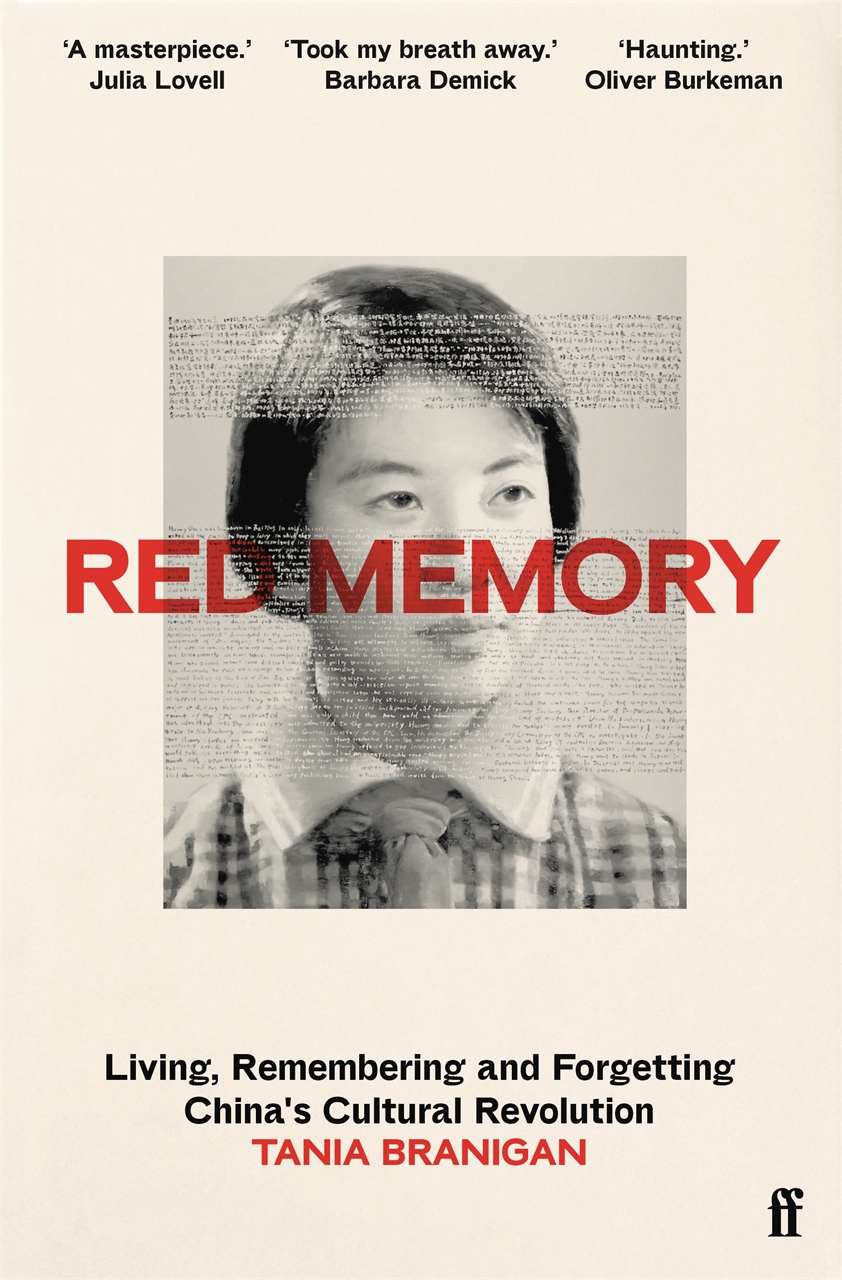

“It is impossible to understand China today without understanding the Cultural Revolution.” This statement lies at the heart of former Guardian China correspondent Tania Branigan’s début book, Red Memory: Living, Remembering and Forgetting China’s Cultural Revolution. It’s a haunting and brilliant exploration of the legacy of the brutal and chaotic decade (1966–76) in which Mao Zedong attempted to destroy his perceived enemies by unleashing the Chinese people on the Communist Party and urging them to purify its ranks. But Red Memory is not just a truth-seeking book about China. By interrogating such questions as, what happens to a society when you can no longer trust those closest to you?, what happens to the present when the past is buried?, and how do you live with yourself once the worst is over?, Branigan has produced a powerful work that has resonances for us all in the face of growing fractures in our own societies.

Now a Guardian foreign leader writer, Branigan was stationed in Beijing from 2008 to 2015, arriving ahead of the Summer Olympics held there that year. When we meet via Zoom, she tells me that while she had no particular ambition to be a foreign correspondent, she had wanted to report from China for a long time “because of its extraordinarily complex, rich history. Being China correspondent was my absolute dream job and I still pinch myself that I got to do it for seven years. The changes I saw in that time were extraordinary—the country was transforming itself at incredible, break-neck speed, and beginning to reassert itself at the forefront of global politics. What always fascinates me in journalism is how such huge changes translate on a human scale. You see this vast transformation playing out in the lives of ordinary people in a way that’s absolutely compelling.”

For all the things that have gone terribly wrong since, her story did give me the sense that there had once been this kind of utopianism and hope; and that people had seen meaning in Chinese Communism

Branigan’s own heritage also played a part in her desire to report from that country. “My grandmother, who is Thai-Chinese, tried to run away to join the Communists in the 1930s but got turned back because the captain of the ship recognised her name and told her parents. One of her friends did make it to China though and spent the rest of her life there. For all the things that have gone terribly wrong since, her story did give me the sense that there had once been this kind of utopianism and hope; and that people had seen meaning in Chinese Communism in a way that was not just naïve.”

Filing stories from Beijing, Branigan soon began to realise how much contemporary China had been shaped by the Cultural Revolution in a way that outsiders barely understand. “I kept going to interview people about what I thought would be other subjects entirely. But then in talking to novelists or film directors about their work for example, I would realise that living through these 10 years—[years] that were ripped out of the fabric of Chinese culture—had a really formative effect on their work. In the West, although people are dimly aware that the Cultural Revolution was a time of incredible cruelty and violence, they have no idea what it really meant. Michael Gove came to China and afterwards wrote a piece about how British universities needed their own cultural revolution!” It was this profound lack of understanding, and the sense of a deeper story beneath, which kindled the idea for a book “that would be compelling for people who wouldn’t normally pick up books on China”.

While Branigan is quick to credit the existing scholarship and books that have been written about the Cultural Revolution, Red Memory tackles that time rather differently by drawing on hundreds of hours of interviews and written testimonies to tell the rarely heard stories of individuals who lived through it, and who are still driven somehow to confront it. Among those we meet are Yu Xiangzhen, former schoolgirl Red Guard; composer Wang Xilin, forced to become a “cultural soldier” who would create new works for the masses; Wang Jingyao, who keeps sacred the memory of his teacher wife Ba Jin, the Cultural Revolution’s first victim in Beijing, battered to death by her pupils; and Wang Youquin, another of Jin’s pupils, who witnessed her killing.

What makes the era’s lessons so vital is also what makes them impermissible

Given the official suppression and personal trauma that have conspired to produce a prevailing national amnesia around the Cultural Revolution, I ask Branigan how she went about gaining the trust of those she interviewed. “I think what was actually striking to me was that some people were starting to come forward, realising that they wanted and needed to talk about what had happened to them. And so at the time, it seemed as if there might be an opening up of a space for such memories, and for a dialogue that was moving slightly more into the public realm.” Yet tellingly, she states in Red Memory—the bulk of which she wrote after returning to the UK six years ago—that “this book could not be written if I were to begin it today… What makes the era’s lessons so vital is also what makes them impermissible.”

Branigan tells me that people in China are now much more nervous about speaking to foreign journalists, who are themselves increasingly criticised and attacked. Current leader Xi Jinping, now beginning a precedent-breaking third term as Communist Party head, is, Branigan writes, “more conscious of the uses and disadvantages of history than any leader before him, bar perhaps Mao himself”. She adds that Xi has previously warned that “historical nihilism”—in other words, any criticism of the party’s past—is “an existential threat on a par with Western democracy… as if control of the world’s most populous nation and second-largest economy might be imperilled by its ghosts and their stories”.

An alarming new perspective

Compellingly for Western readers, Branigan’s time in China also threw an alarming new perspective on other parts of the world, including her UK homeland. “I learned more about my own country from China than I could have imagined,” she writes. When I ask her about this, she says: “I’m not drawing direct comparisons, or saying we’ll have a repeat of the Cultural Revolution in this country. It’s a very particular event that happened under very particular historical circumstances. But I find resonances of it in wider human behaviour: the whipping up of fake culture wars; the emphasis on emotion at the expense of fact and rationality, with the storming of the US Capitol in January 2021 perhaps the most glaring example. I’m not the first person to see Trump, with his love of disruption, as a very Maoist figure and I don’t think we can afford any complacencies around that, or our own government’s efforts to push back on people’s fundamental right to protest, for example”. Red Memory is, she says, a book that has turned out to be “more topical than I anticipated and also more topical than I would have hoped”.

Extract

I wanted to understand not only what the Cultural Revolution had done to China, but how it was still shaping it. The subject has not always been as sensitive in China as it is today, and remarkable research has been done within the country, despite the risks, often by those who survived the era. Plenty of books have been brought out in Hong Kong, which used to have spirited independent publishers, as well as outside China. But the memoirs and histories I read perplexed as much as enlightened me. They never fully answered my questions: not about what had happened, and how, and why, but about how the country lived with it, what it meant and why it mattered now.

The use of the word “Cultural” to describe a movement that may have resulted in as many as two million deaths might appear strange. But Branigan argues that the Revolution was “fundamentally about trying to change culture in the broadest sense, from the arts, right through to how people related to one another”. Therefore, she says, the Cultural Revolution tells us something crucial about how tightly our day-to-day cultural and social interactions are tied to democracy and to our human rights. “They are not add-ons, they are not trivial or ephemeral. They fundamentally shape us.”